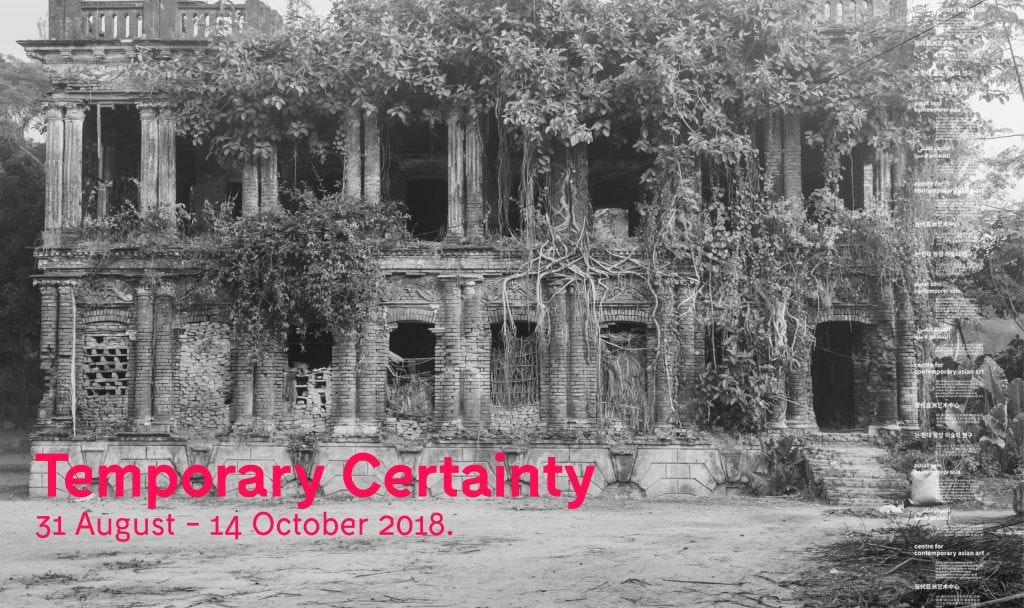

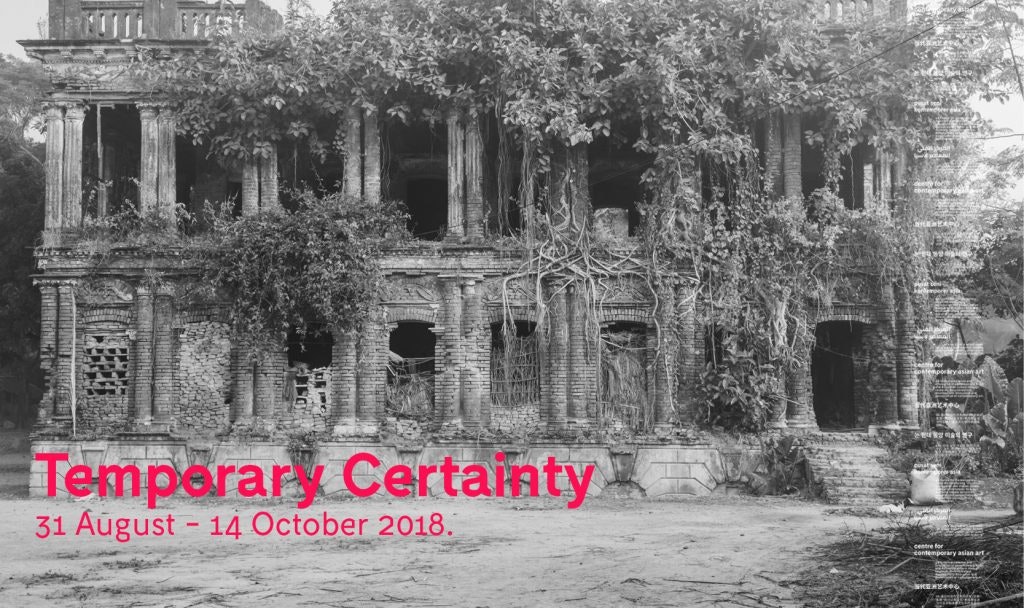

Temporary Certainty

When

31 August 2018 -

14 October 2018

Location

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

181-187 Hay St, Haymarket

Temporary Certainty is shaped by an investigation of sudden shifts of historical change wrought by complex interventions in the greater Asia region. Showcasing new works from Australian artists Rushdi Anwar and Alana Hunt alongside a new body of work from Sarker Protick, this exhibition brings together three distinct voices that share long-standing commitments to humanitarian and activist concerns. With a focus on Bengal, Kurdistan and the Kimberley region of Western Australia, Temporary Certainty explores how artists approach geography as a marker of the consequences of broader geopolitical expediencies.

The three distinct geographical contexts represented in this exhibition, each with their seemingly disparate environmental challenges and contingencies, are here connected by the way the artists have explored questions of nationalisms, the legacies of sovereignty, and contested narratives of memorialisation. Equally defined by more urgent concerns and experiences of displacement and transience, the works presented in Temporary Certainty are distinguished by their emergence within conditions of uneasy reconciliation. Additionally, a common thread between each artist’s vision across the works presented in this exhibition is the central importance of the photographic image as a medium that excels at mediating between space and time, reality and illusion. The artists utilise this visual language, alongside other mediums and methodologies, in a shared pursuit of seeking to unveil the symbolic resonances that inhabit built environments within fractured contexts.

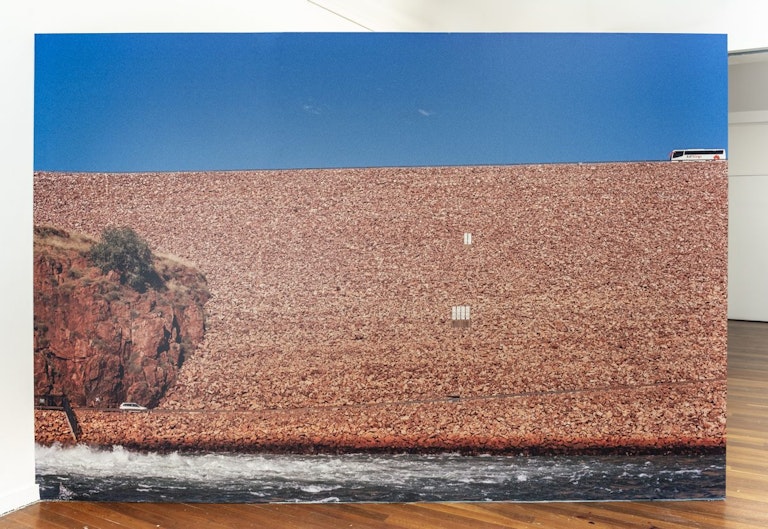

Alana Hunt’s activities as an artist are defined by her commitment to broadening and challenging the possibilities of communicating ideas in the public realm. For Temporary Certainty, Hunt has created a new work, Faith in a pile of stones (2018), that takes as its focus Lake Argyle. Located near the artist’s home in the town of Kununurra, Lake Argyle was constructed in 1971 (and filled by 1974), following the damming of the Ord River. An immense human-engineered reservoir of freshwater whose capacity is more than eighteen times the volume of Sydney Harbour, its construction for the purpose of irrigation for agricultural production drowned places of significance and altered the ecologies of country belonging primarily to Miriwoong, but also Gija and Malgnin people. Hunt reconfigures the monumental aspect of the dam wall in a work that explores the convergence of the bureaucratic management of natural resources driven by colonial dreams of development that have been shaped by faith in the idea of permanence.

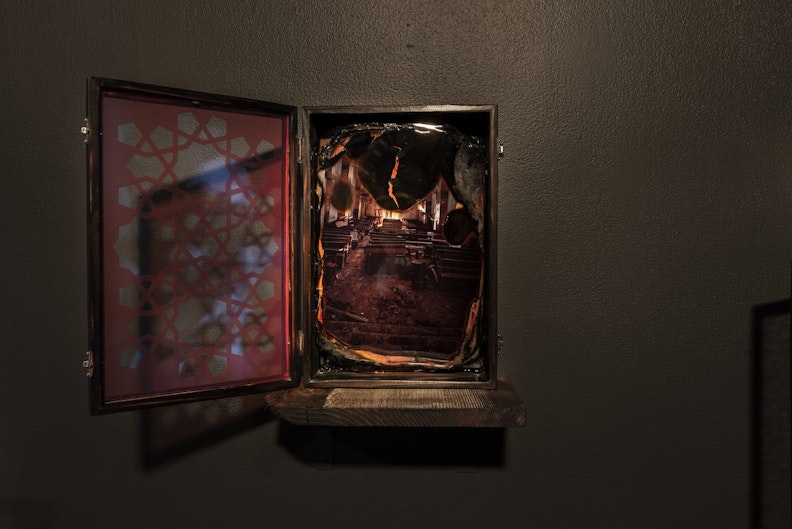

Rushdi Anwar presents two works that are deeply related to the artist’s experiences as a member of the Kurdish diaspora. The video and sound installation Facing Living: The Past in the Present (2015) shows a pair of hands that proceed to tear up and piece back together an official portrait of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein until the image is overwhelmed by black adhesive tape, an act that balances between destruction and creation, erasure and elegy for those who suffered under Hussein’s rule. We have found in the ashes what we have lost in the fire (2018) is the artist’s response to his recent experience of entering a church in the town of Bashiqa located in north east Mosul, part of disputed territories between the Kurdistan Regional Government and Iraqi government. This work explores unsettling similarities between the destruction, transience and renewal faced by displaced and uprooted communities globally and the built environments they are forced to leave.

Sarker Protick’s Exodus (2015–ongoing) considers the expediencies of decolonisation while at the same time being a haunting meditation on the universal contingencies of time. Over a selection of photographs and moving image, the artist explores the decaying buildings and surrounding lands of the feudal estates in East Bengal that were previously owned by Hindu jamindars, or landlords. Following the Liberation War of 1971 that abruptly established the newly independent nation of Bangladesh, huge migrations took place across Bengal. This saw wealthy Hindu landowners abandon their estates for India in fear of the kind of violent reprisals that had erupted following the Partition of India in 1947, while at the same time many Muslims fled West Bengal heading east. A series of controversial laws dating from 1948, culminating in the Vested Property Act of 1974, allowed the confiscation of property by Bangladeshi authorities from groups declared ‘enemies of the state’. Since then, these estates have commonly been left in disrepair, taken over by nature and appropriated by local villagers—another chapter in a landscape indelibly marked by the influence of Mughal rule and British imperialism (1).

Grappling with tensions between certainty and doubt, permanence and all that is ephemeral, Temporary Certainty contemplates the value of what can be apprehended—much less held onto—with any guarantee in an age lurching towards ever greater polarisation.

Temporary Certainty is produced by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Rushdi Anwar’s commissioned work has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. The presentation of Sarker Protick’s Exodus has been supported by The Esplanade, Singapore, with additional support from the Australian Centre for Photography.

(1) Sarker Protick’s Exodus was internationally premiered in the exhibition The Life of Things at The Esplanade, Singapore, from 19 January to 8 April 2018. This text incorporates aspects of curator Sam I-shan’s accompanying text for this exhibition.