Not Your Steppe’s Stone

Vladislav Sludskiy

Central Asia is a vibrant geographical area where many cultural identities and historical narratives intersect. On the one hand, there is a strong and lasting presence of nomadic heritage from the Saka tribes, which inhabited parts of Central Asia in about 170 BC. Then there is the enduring story of the Silk Road, which spans from the modern territory of Europe, through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and all the way to Far East China. This route became one of the first trading ecosystems that fostered the exchange of goods and ideas.

Parallel to that, Turkic and Islamic traces can be seen in architecture, clothes, cuisine, jewellery, and verbal traditions. All of these influences gradually melted down into the 69 years of Soviet rule that collapsed in 1991. The people within this region started to deconstruct, analyse, and rethink their territorial and cultural borders, their heritage, and their place in the history of civilisation. The ongoing investigation of such imprints takes place today in the context of postmodernity’s multidisciplinary, timeless and inclusive dimensions, allowing all of the above to co-exist.

Kazakhstan is a country known for its cultural, financial and industrial activities. Yet Almaty—the biggest city in Central Asia and former capital of Kazakhstan— has only a few museums, institutions and artists. This essay provides a glimpse into the practices of selected Kazakhstani artists and art collectives in an effort to spotlight the cultural scene of this relatively unknown and institutionally-underrepresented region.

Artists and Art Collectives

Kyzyl Tractor Art Group – members: Arystanbek Shalbayev, Said Atabekov, Smail Bayaliev, Vitaliy Simakov, Moldakul Narymbetov

Kyzyl Tractor Art Group is a transavantgarde artistic tribe that was formed in the early 1990s, soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Group were among the earliest contemporary artists in the region to experiment with performance, appropriating the Zoroastrian wing of Islamic tradition called Sufism and mixing this with nomadic rituals of purification and a touch of self-irony. In the 1990s, the artists lived as an anarchic commune outside of Almaty, producing wood sculptures, playing national musical instruments, making paintings, and developing ideas for their art. When looking at former Soviet countries, one needs to understand that the advent of Postmodernism was slightly delayed compared to the conventional art history perspective that sees the new era in world culture starting immediately at the end of the Second World War. With no access to information, and physical isolation, artists from Kazakhstan caught up with the context and vocabulary of contemporary art in the late 1980s, with the advent of Perestroika. It is fascinating to witness the rapid transmission from one paradigm to another, the vivid morphing of tradition and post-colonialism, of the old and the new.

Arystanbek Shalbayev, The Game, Matches and Barrels Series, 2010, acrylic on canvas with wooden frame, 144 x 144cm; image: courtesy the artist

Foreground: Moldakul Narymbetov, Balbals, 2011, rubber, stone, epoxy resin; Background: a series of works by Moldakul Narymbetov, 2011 – displayed at Asia Contemporary Art Week, 2018; photo: Michael Wilson, courtesy Asia Contemporary Art Week and Eurasian Cultural Alliance

Moldakul Narymbetov (1946-2012) was a practicing shaman, musician, sculptor and performer. The above image shows Narymbetov’s paintings and resin sculptures; the black sculptures with stones on the top are made out of used car tires collected by the artist near his studio, outside of Almaty. The title, Balbals, refers to the pieces of stone or wood located across a large grassland, or steppe. Ancient nomadic Turkic and Mongol tribes did not have centralised cemeteries, since they were constantly on the move. Narymbetov created this work in response to this past tradition by using recycled materials and combining them with stones from the South of Kazakhstan, a historical destination for all sorts of pilgrimages.

Saule Suleimenova (b. 1970)

Saule Suleimenova Skyline, 2017 Plastic bags on polycarbonate triptych, each 200 x 200 cm. (78.7 x 78.7 in)

Saule Suleimenova is a female artist whose latest body of work consists of figurative paintings made solely out of used plastic bags. Her choice of plastic as the main material for the Cellophane Paintings series (2015-ongoing) is not accidental or spontaneous. For decades, Kazakhstan has been glorifying oil as the primary driving force for its economic growth and as an ideological pride for the political and corporate establishment. Simultaneously, Kazakhstan’s poverty levels, increasing social stratification, and diminishing human rights have gradually hindered the formation of a healthy, liberated nation with a strong culture. Plastic—essentially a carbon-containing compound made out of oil—becomes an ideal metaphor for this traumatising economic cycle and, subsequently, of the cultural processes as well. What starts off as an enrichment tool for a select few at the beginning stages of the supply chain ends up in millions of households in the form of ripped up, used up, and crumpled plastic bags from numerous department stores.

To recontextualise Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan’s famous theory from 1964: the medium is the message in Cellophane Paintings. Suleimenova’s Kelin (Bride) also uses plastic bags as its main medium, based on a 19th century archival photo of a young Kazakh bride. The work yet again loops the past and the present, a tactic so common to the contemporary artists of today.

Saule Suleimenova, Kelin (Bride), 2015, plastic bags on polycarbonate, six panels, each 200 x 200cm; installation view, group exhibition: Post Nomadic Mind in London, 2018; image: courtesy the artist and The London Magazine

Saule Suleimenova, The Exodus of the Kazakhs, 2018, Asharshylyk series, plastic bags on polycarbonate, 125 x 149cm, collection of Sharjah Art Foundation; image: courtesy the artist

Erbossyn Meldibekov (b. 1964)

Erbossyn Meldibekov (b. 1964)

Not everyone, however, is looking at the distant past. The conversation about the formation of a new national identity, ideology and nation-building plays a significant role in understanding current cultural processes. Some contemporary artists in Kazakhstan are in search of innovative ways to look at the present without glorifying the past. There are similarities with the works of artists in the Chinese avant-garde movement. In 1995, Ai Weiwei photo-documented the destruction of a 2000-year-old ceremonial artefact in his iconic work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. Xu Bing invented his own hybridised language by intertwining Chinese characters with English letters, resulting in the ongoing project Square Word Calligraphy. Similarly, Qin Feng’s Portraits of the Great (2014) disrupted conventional ink painting traditions and methods by fusing traditional calligraphy brush strokes with contemporary aesthetics, with a hat nod to abstract expressionism.

Erbossyn Meldibekov’s work centers around the ephemeral qualities of these ideologies, and goes hand in hand with political shifts of the past century. His transformative sculptures refer to the obsession of the young republics, such as Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Ukraine, and the ways in which their cities, streets, squares and monuments are constantly being renamed.

Transformer was installed near the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow from June to November 2020. It recalls the Amir Timur Square in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, which has been renamed six times in the past 100 years. Nursultan, the current capital of Kazakhstan, has also had a number of different names, including Akmola Akmola (white grave), Tselinograd (deriving from tselina), and more recently, Astana (the capital).

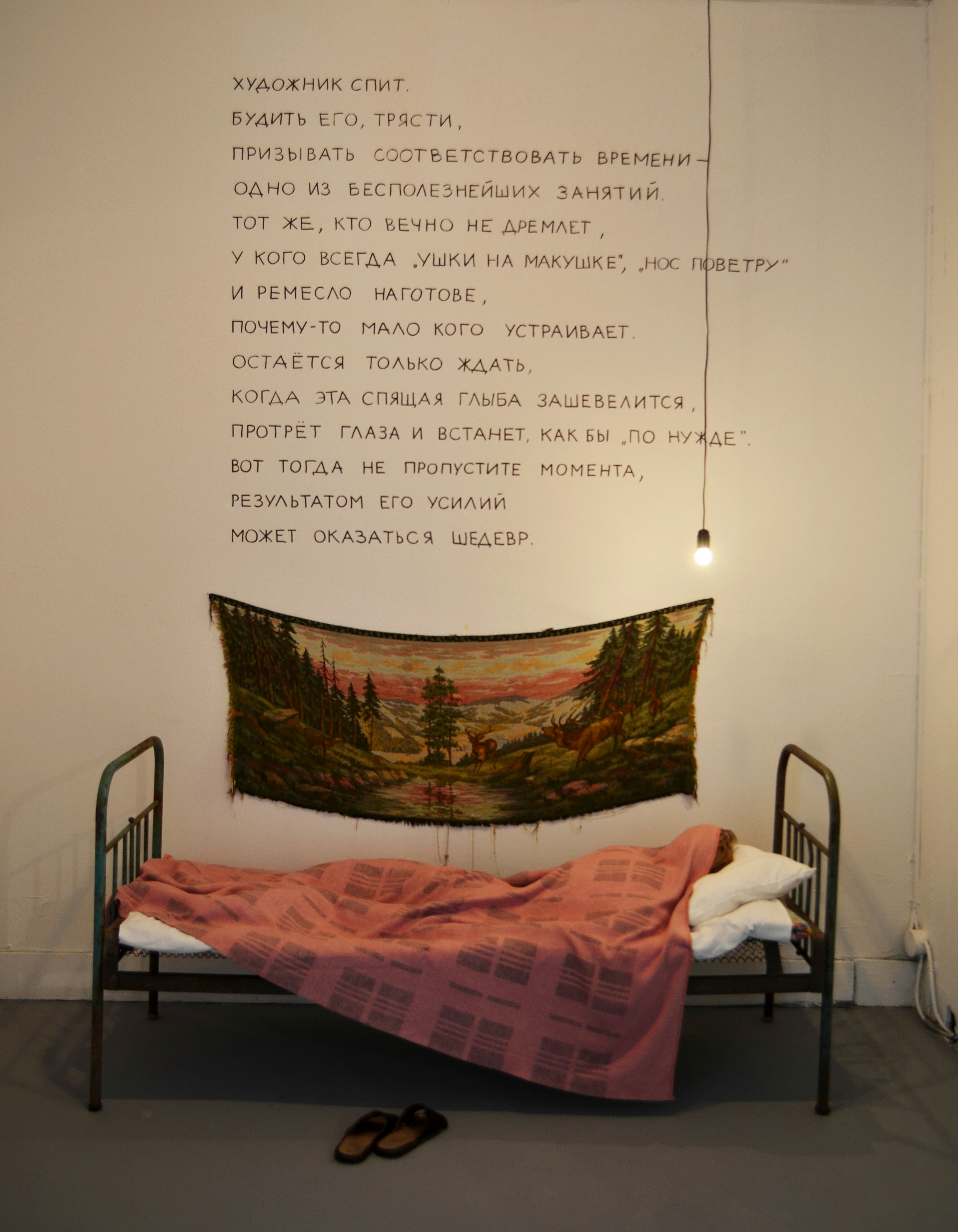

Yelena and Victor Vorobyev

Blue Period (2002-2005), by husband-and-wife artistic duo Yelena and Victor Vorobyev, also explores the ways in which ideology leaks into pop culture and national symbolism. The light yet vivid blue colour of the Kazakhstani flag is the nation’s primary choice when it comes to painting all kinds of domestic objects, including fences, shopping carts, balconies, branches and so on. Most often, it is the city hall that uses these colours as a particular sign of loyalty to the regime. Blue then becomes, perhaps, the only consistent visual code linking the nation both vertically (from governmental to the civic) and horizontally (from citizen to citizen). Though it is fair to say that in recent years the tendency has been slowly fading away just like the patriotic moods of the late 1990s. Looking internationally, in 2017, Christine Macel, chief curator at the Centre Pompidou, included the Vorobyevs in her edition of the 57th Venice Biennale. This marked the first time Central Asia was represented in the history of the Biennale, and involved a re-creation of the duo’s 1996 installation The Artist is Asleep in the Italian pavilion.

Yelena Vorobyeva and Viktor Vorobyev, The Artist is Asleep, 1996, installation, mixed media; courtesy the artists and Aspan Gallery

Marat Dilman (b. 1990) and Anvar Musrepov (b. 1990)

While artists of this new generation are also enthused with the search for various forms of identities, the optics they use carry less locality. Certain ornaments and traditions are still present, however, the immediate visual sense is of a post-analogue genre developed after the Internet epoch, which denotes the pervasiveness of digital media.

Marat Dilman is a photographer who produces around six artworks a year. His bright, colour-rich images are an ongoing attempt to juxtapose new technologies with motifs that hark back to nationalism traditions. In doing so, Dilman lovingly pokes fun at Kazakhstan’s coexistence of capitalistic and archaic exchanges.

Examples include a giant yurt installed temporarily in a city square in Almaty for a holiday celebration, or a CCTV camera dominating the landscape near the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi in Turkestan. These architectural columns act as a certain tapestry of contemporary cities of Central Asia where old and new converge in seemingly obscure ways.

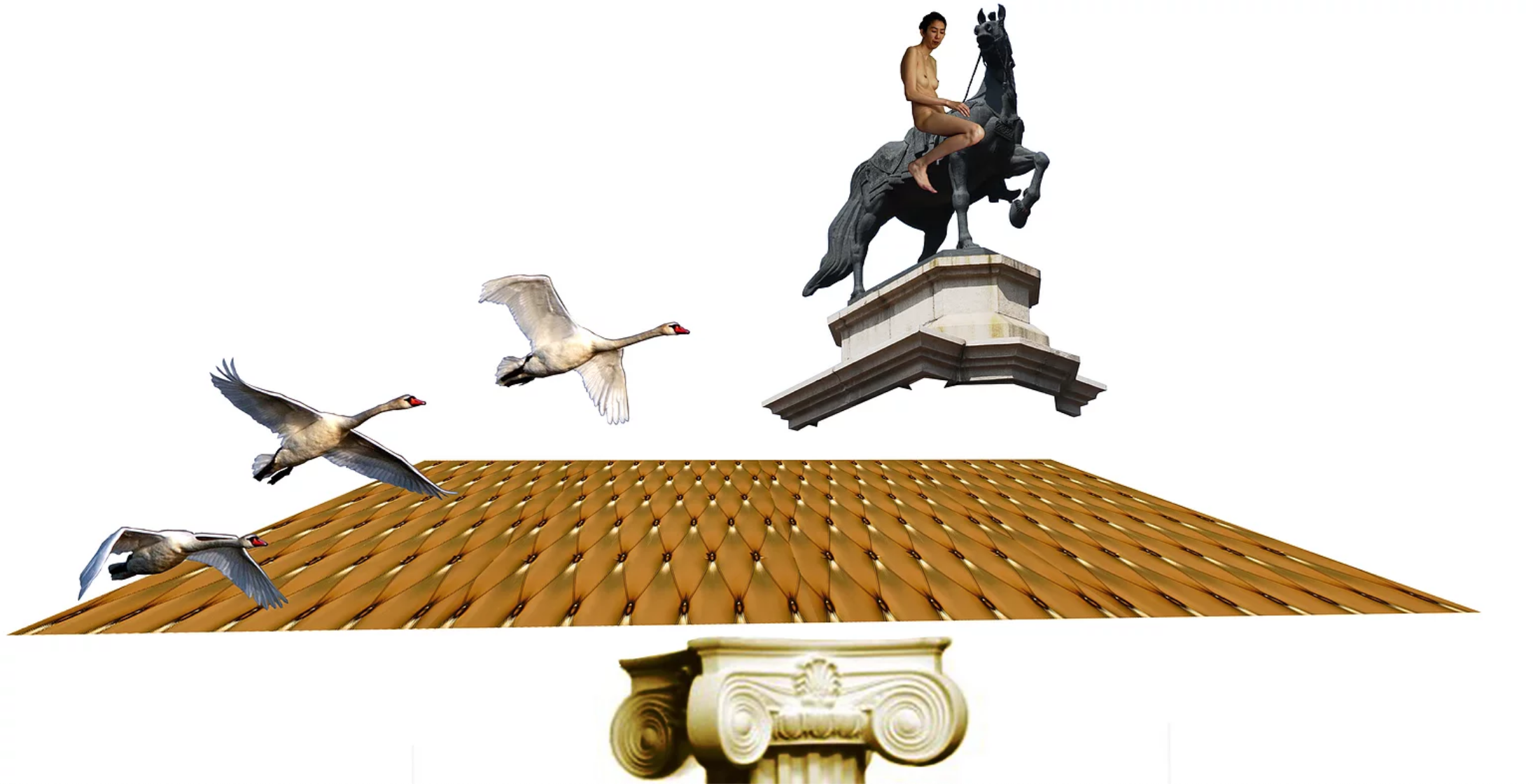

Anvar Musrepov, to the contrary, steps aside from the physical dimension to create his own avatar in jigitovka, an animated video that sees him take on the role of a brilliant horse rider, atop a three-dimensional rendering of a horse. The word jigitovka is of Turkish origin and refers to a special style of trick horse riding in Central Asia. Given how few horses remain in the contemporary cities of Kazakhstan today, this digital work empowers Musrepov to embrace his Kazakh identity in a way he isn’t able to in the real world.

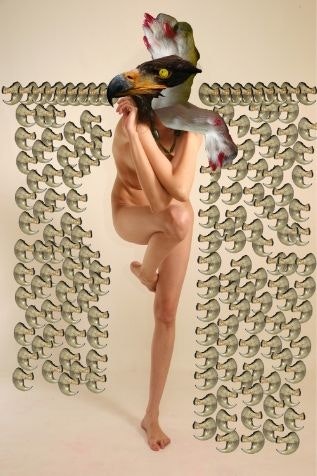

Baha Bubikanova (b. 1985) and Zoya Falkova (b. 1982)

Baha Bubikanova’s practice seeks to debunk notions of body politics by demystifying the socio-political structures placed upon female bodies. Her works consist of surreal acrylic paintings, humorous performances that convey institutional critique, and digital collages depicting elements of lowbrow culture that almost fall into the universal kitsch so common in the newly developed economies. Bubikanova appreciates quasi-Greek columns that she classifies as Kazakh Baroque. She also paints ram heads and sells them at the exact price of the last stimulus cheque – ₸42,500 (roughly USD $100) – that every registered citizen received during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a fashion that’s rare in seemingly religious societies, Bubikanova incorporates her body in her photographs and collages.

Zoya Falkova is a feminist artist who teaches art history at Kimep University, and actively exhibits in Kazakhstan and internationally. She uses experimental materials such as borscht (Eastern European soup), floorcloths, ants and seeds. Her artwork Colonization of Marx plays around a utopian idea, conceived by the futurists of the 20th century, of the extension of our civilisation to other planets, while also exploring the idea of ants as perfect communists. The artist creates a portrait of Marx inside of the formicarium and inhabits it with red ants. As the exhibition goes on, more ants colonise Marx.

Galleries and Institutions

Although the past four decades have demonstrated an encouraging direction towards progress and healthy integration of Central Asia’s art community into a global conversation, local institutions and galleries are still far away from functioning at their full potential. There are currently no international-standard art fairs, no museums focusing on contemporary art, and no globally-recognised private collections that concentrate on the emerging art scene of Kazakhstan and Central Asia. A transition from the economic model of collectivism to that of capitalism seems to be occurring, albeit slowly, after many years.

There are several globally renowned institutions that pay significant attention to the older generation of Kazakhstani artists, but the list is rather short: Zimmerli Museum of Fine Arts in New Jersey, Center of Pompidou in Paris, Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, Asia Society in New York, Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and Fondazione 107 in Italy, to name a few. The National Museum of Fine Arts, named after Abilkhan Kasteyev in Almaty, is perhaps the only entity in the country that possesses serious artworks by living contemporary artists, with most of the pieces either donated or collected in the 1990s. Sergey Maslov, Moldakul Narymbetov, Alexander Ugay, Georgy Tryakin Bukharov, Saule Suleimenova, Almagul Menlibayeva, Elena and Victor Vorobyev, Kuanysh Bazargaliyev, and a dozen other names are on permanent view in the hallways of the Kasteyev. It’s also the only museum that dedicates a portion of their spaces to contemporary art. The National Museum of Fine Arts also has a strong collection of Socialist Realism and some Russian Avant-Garde pieces that were donated by the Pushkin and Hermitage Museums, which has been under the watchful eye of the Soviet propaganda machine for decades. No consistent budget exists for new acquisitions as the Ministry of Culture dedicates most of its focus on the music and film industries, rather than fine art preservation. It should be mentioned that the Ministry succeeds only in developing cinematography and music, mostly as a tool for ideological goals of the regime without contributing much to the actual culture.

There are several galleries in the region, and the most supportive of all is Aspan Gallery located in Almaty, which has a consistent program of five exhibitions a year and occasional presence at art fairs, such as Art Dubai and Art Stage Singapore (now closed). A substantial contribution of this gallery also includes publications and catalogues on works by Erbossyn Meldibekov and Elena and Victor Vorobyev, produced by the scholar and curator Victor Misiano.

As a smaller gallery, Artmeken features a less dynamic program but an equally impressive roster of younger generation artists, including Roman Zakharov, Sabina Kuangalieva, Zoya Falkova, and Katya Nikonorova. Tse Art Destination is a Nursultan-based gallery that exhibits important local artists such as Zauresh Terekbay and Galim Madanov. The gallery is instrumental in discovering new names and shaping overall cultural trends inside the country. There is a great deal of hope for the late 2021 opening of the Center of Contemporary Culture Tselinny, the first centre of contemporary culture. The team at Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art have consulted on the development of this project, which is encouraging, although time will tell if the centre succeeds in its venture. Meanwhile, Esentai Gallery changed owners at least four times in the last decade, and despite its numerous attempts to create a sustainable program, the gallery struggles due to the relatively unstable market and high operational costs.

Qazart.com embodies another commercial model. Launched in 2019, it’s an online platform with no physical space that aims to connect artists, curators, scholars and collectors by reaching out to the external markets. Eurasian Cultural Alliance, one of the oldest organisations, has been operating in the field of contemporary art in Almaty since 2010. (1) Its main areas of concentration include educational initiatives such as the School of Artistic Gesture and the festival of contemporary art ARTBAT FEST, which has been dwindling in size because of the lack of consistent funding. More recently, the organisation switched to the consulting model to redistribute funds to the local market. As a result, Eurasian Cultural Alliance now provides expertise in the areas of public art, the local market, and international blue chip artists, with the aim to link the art scene of Kazakhstan with global collectors and local capital so that established and mid-career artists are represented around the world.

Notes

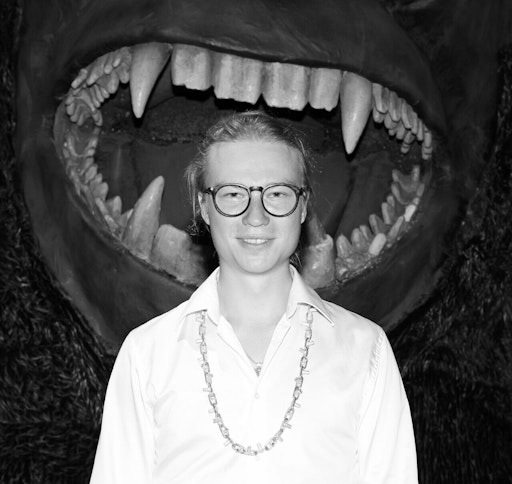

Vladislav Sludskiy founded Qazart in 2019 and is also the co-founder and curator for the Eurasian Cultural Alliance. He is currently an active figure within both these organisations.

About the contributor

Vladislav Sludskiy is a Senior Art Consultant at Metis Art Education, the Former Director at Ethan Cohen Gallery, New York and co-founder of the Eurasian Cultural Alliance and Qazart.com