A mere drop in the sea of what is

Alana Hunt

I

On 7 April 2016, 70 000 people attended the funeral of Waseem Ahmed Malla and Naseer Pandit in the Shopian district of Indian-occupied Kashmir. On 9 July, three months later, 200 000 people attended the funeral of Burhan Wani, Sartaj Ahmad Sheikh and Pervaiz Ahmad Lashkari in Pulwama and Anantnag (locally known as Islamabad) districts of Indian-occupied Kashmir. Thousands more attended funeral prayers in absentia across Kashmir. Waseem, Naseer, Burhan, Sartaj and Pervaiz were all armed fighters, local mujahideen struggling against India’s longstanding occupation of Kashmir. Indian forces killed all of them.

Kashmir has been shaped by centuries of foreign rule. Its latest incarnation—the most ‘modern’ and most ‘democratic’—is also its most brutal. Today, the mountainous Himalayan region sits occupied and divided between India, Pakistan and China. The situation is a product of Britain’s partition of the subcontinent, when lines of nation states were arbitrarily marked on maps as the British Empire reckoned with its own demise after the Second World War. For nearly seventy years, people in Kashmir have been thinking, talking, fighting and waiting for the right to self-determination. They have been promised a plebiscite that has not yet come. Over 70 000 people have been killed since 1989, mostly in India’s counterinsurgency operations against Kashmir’s popular armed movement. Kashmir is a torn place; endless kilometres of barbed wire run like open veins across its surfaces. Though definitions will vary, as they should, people across Kashmir speak, breath and dream of azadi (freedom). Waseem, Naseer, Burhan, Sartaj and Pervaiz died for it. And like so many, many others they died because of its absence.

I learnt of Waseem and Naseer’s martyrdom when images of their funeral flooded my social media feed. In one telling image, the photojournalist Muneeb Ul Islam did not photograph the funeral procession, but instead turned his camera to witness, record and share the intense need of those in attendance to witness, record and share. The image is full of faces and hands and mobile phone cameras. Within minutes another image of people attending Waseem and Naseer’s funeral stopped me in my tracks. It had been taken on the mobile phone camera of Javaidd Naikoo. In this image, the deep-seated need to bear witness is again ubiquitous. So much so that piercing the height of the crowd are around twenty men clinging to tall lean trees as though they were lookouts on a ship. The image is still, but you can almost feel those men in the trees swaying in the breeze above a sea of salty-eyed people in mourning.

Mourners watching the funeral of Waseem Ahmed Malla in Aglar-Shopian on 7 April 2016; photo: Javaid Naikoo.

These two photographs embody what the word and name shahid mean for Kashmir today. In Arabic, shahid, and its close derivative shaheed, mean witness and martyr respectively. Within Islam a martyr is not only a witness to great injustice, but one who offers the ultimate sacrifice of life to fight the injustice that has been witnessed. The late Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali touched on these dual meanings in his poetry about Kashmir in the 1990s. As an allegorical tool to think through Kashmir today, the ideas within the word shahid are still as pertinent as ever. These two photographs are like a divination of sorts. They forewarned the magnitude of what was to come only three months later with the death of the very popular Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani and the continuing uprising of 2016 that his martyrdom helped to catalyse.

In the month following Burhan’s death, the occupying Indian state has responded to the local uprising with extreme violence. Over ninety Kashmiri civilians have been killed. They have been shot or beaten to death while mourning, protesting and, in some cases, while simply being at home. Pellet guns have blinded hundreds of people, children included. Thousands more people have been injured. At the most crucial moments, internet and phone networks are disabled, making communication within the region and outside difficult, if not impossible. Newspapers have been raided—in the case of the daily Kashmir Reader, banned completely. Reports says 15 000 people have been imprisoned under the draconian Public Safety Act (PSA), including the internationally renowned human rights activist Khurram Parvez. There have been many reports from different places in Kashmir of Indian armed forces burning the kharif crop of paddy, pulping the ready-to-be-shipped apple produce, and killing livestock. But there is much more to Kashmir than violence and victimhood.

I’ve been watching Kashmir through social media from Australia for a number of years. Over the last few months a literal and conceptual skirmish around visibility and blindness has unfolded. It stems from the need to render the various states of blindness inflicted on Kashmiris by the Indian state visible. It is about breaking through the blind spots of the Indian and international community’s collective imaginations. It is about Kashmiris communicating with each other in newer ways, building solidarity in times of need with defiant acts of creativity in response to the ongoing violence. This is taking place through a visual counterculture of images, videos, texts and sounds that circulate as memes online and manoeuvre the turbulences of Kashmir’s brutal occupation and its aspirations for azadi with wit, intelligence and timing. The content is as horrifying and tragic as it is inspiring, astute and affective—to the point that the Indian government recently cited ‘social media’ as their number one concern in the region of Kashmir they militarily occupy with over half a million armed personnel.

Kashmiri documentary filmmaker and writer Sanjay Kak described the 2010 uprising as an intifada of the mind, one shaped by incisive critical thinking, ideas, and the power of words. In many ways the 2016 uprising could be understood as an intifada of sight. Those who bear witness carry a heavy responsibility to defy blindness and their own invisibility. It has been said that the new wave of armed struggle in Kashmir, which Burhan Wani represented, understands that it can fight the Indian occupation more successfully with images than it ever could with weapons.

What follows is a discussion that is by no means exhaustive. It is a snapshot of what I have seen from Australia via social media this year, which in turn represents a mere drop in the sea of what is.

II

Image courtesy Aarabu Ahmad Sultan, as reported in BBC News, 19 July 2016.

First used in Kashmir in 2010, pump action shotguns capable of firing hundreds of tiny lead pellets from individual cartridges at high speed over wide impact perimeters have become the weapon of choice for Indian forces in Kashmir. They are inaccurate, indiscriminate and, despite claims of being non-lethal, have proven to kill efficiently. From early July through to early August of this year alone, over 1.2 million lead pellets were fired in Kashmir.

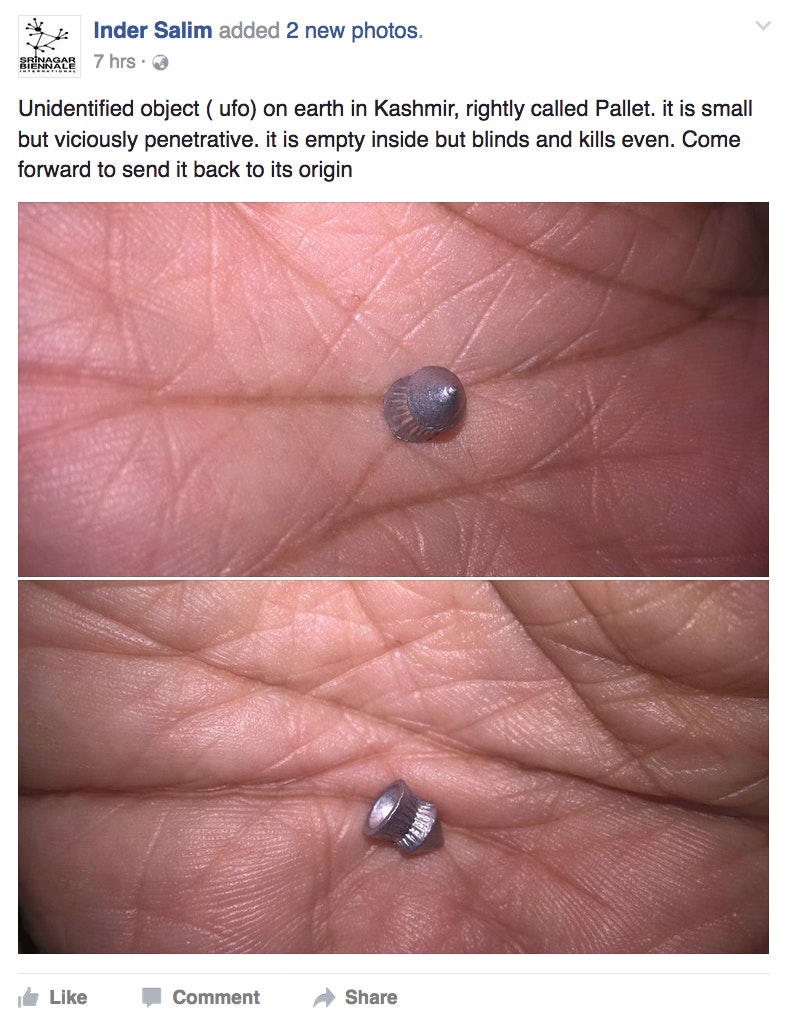

X-ray images of bodies full of lead pellets went viral on Facebook within days of Burhan’s death. Indian graphic artist Orijit Sen’s Agony Map of Kashmir was one of the first visual memes to creatively respond to what was happening in Kashmir at this time. A digital collage produced on a photograph by Yawaz Nazir, Agony Map of Kashmir depicts the names of places across Kashmir over individual pellet wounds on a young man’s back. Although the image appears like a map it is not geographically accurate. Orijit has used the visual motif of a map to register agony not geography. When it first appeared in mid-July I remember this image shocking me. Now it feels tame. Similarly, the Kashmiri performance artist Inder Salim—whose life, art, body and identity coalesce into one bold, intuitive and often controversial body of work—has also been thinking about pellets, though in more symbolic ways. Brimming with commentaries and performative acts about his homeland, in one work Inder spells the word azadi from pellets wedged into a traditional Kashmiri peasant cap.

Agony Map of Kashmir (2016), digital collage by Orijit Sen on a photograph by Yawar Nazir.

Performance artist Inder Salim’s responses to the use of pellets during the 2016 uprising in Kashmir.

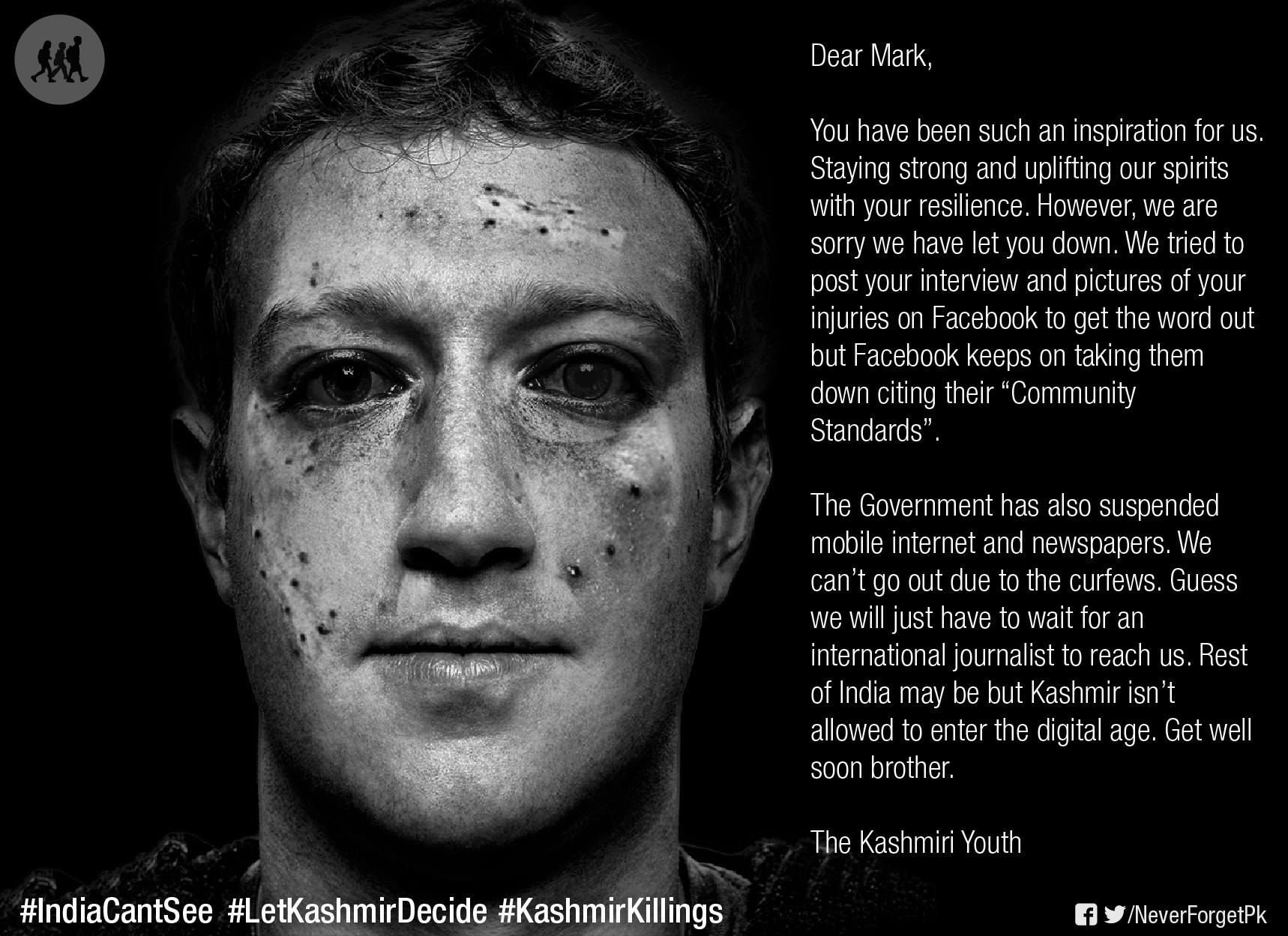

As images of injured Kashmiris were met with general indifference in other countries, including India, the online campaign #Indiacantsee asked, What if you knew the victim? Launched by Never Forget Pakistan, a group of concerned civilians working to build a counter-narrative to extremism in Pakistan, the campaign included a series of 11 digitally altered black-and-white portraits of famous people, including Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, Bollywood actress Ashwariya Rai and the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, all seen with pellet wounds to their faces. Letters from Kashmiris that spoke of what was happening on the ground in Kashmir accompanied the images. The letters were informative and provided context, but the campaign’s ultimate power lay in the simplicity of the monochrome portraits of ‘people we know’. Shared thousands of times online, #Indiacantsee made BBC News, Buzzfeed and other media outlets. Never Forget Pakistan explained:

We condemn and lament the criminal silence and inaction of the Indian Government and cultural icons of India. Furthermore we strongly condemn the pick and choose policy of Facebook which conveniently censors posts highlighting the plight of Kashmiris and later excuses itself by calling the censorship a ‘mistake’.

Social media meme from the campaign #Indiacantsee created by Never Forget Pakistan.

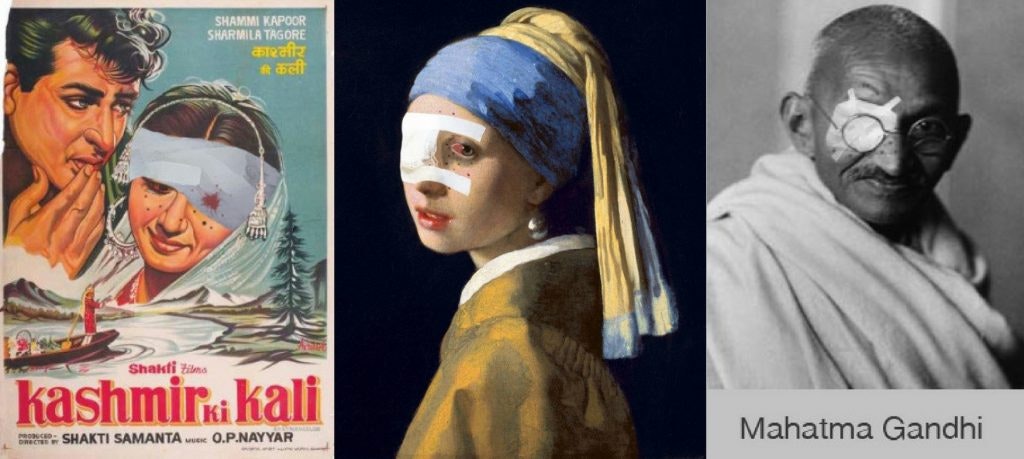

Mir Suhail Qadiri is a political cartoonist and artist from Kashmir whose mischievous and penetrating work has captured the political history of contemporary Kashmir in recent years. In early August, as Indian forces continued their brutal crackdown on the uprising in Kashmir, he released a disconcerting collection of images that mobilised popular culture to draw attention to what was happening in Kashmir. In a poster of the iconic 1960s Bollywood film Kashmir ki Kali (The Bud of Kashmir), actress Sharmila Tagore is seen bandaged and bleeding. The popular tourism campaign ‘Incredible India’ is sardonically turned into ‘Incredible Kashmir’ with bruised, battered and pellet-ridden bodies placed in the iconic landscapes of Kashmir so treasured by India’s popular imagination. Highlighting the hypocrisy of India’s occupation of Kashmir, Indian freedom fighters—like Nehru, Gandhi, Bhagat Singh and Chandra Shekhar Azad— appear with pellet wounds and bandaged eyes. These national heroes were once viewed as terrorists by the British in much the same was as India views Kashmir’s freedom fighters today. Turning to cultural icons of Western art history, Suhail produced A History of Art in Kashmir, inflicting the Mona Lisa, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring and many more with pellet injuries and bandaged eyes.

On 10 August, staff at the SMHS Hospital in Srinagar covered their eyes with patches to express solidarity with the pellet-hit victims they were caring for. The action garnered international attention. See our blindness is a phrase that appeared on one of the placards. The phrase almost begs, but it also demands that people acknowledge the violence that is happening in Kashmir every day, the violence whose victims the hospital staff work for day in and day out. See our blindness compels people to witness. And with witnessing comes a degree of implication and responsibility. The repeated metaphor of the bandaged eye—damaged, shut, unable to bear witness—has become synonymous with the uprising of 2016. It represents the injured, blind and dead in Kashmir. It symbolises the blindness of those outside Kashmir. It also provides an entry point for those of us outside Kashmir to see, to acknowledge and to begin to understand.

Appropriated images courtesy Mir Suhail Qadiri.

III

August 15 is India’s Independence Day. While celebrations take place around India, in occupied Kashmir there is desolation. In Kashmir, the day is now associated with curfews, enforced participation and unusually symbolic happenings. In 2010 a shoe was thrown at the then Chief Minister of the state Omar Abdullah as he unfurled the Indian flag in Kashmir’s summer capital. This year, as the current Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti attempted to do the same, the flag mysteriously fell to the ground. The Chief Minister persisted and with the help of security guards (whose appearance resembled characters from the Hollywood film Men in Black), she stood for a moment very awkwardly displaying the Indian flag. A police enquiry was ordered to find out why the flag fell, and as the story circulated online Ather Zia, a Kashmiri academic, joked that even the forces of gravity were put under scrutiny in Kashmir. The timeliness of the event was better than fiction could ever be.

At around the same time, a cow was seen walking the streets of Srinagar with a Pakistani flag painted on its flank. Given India and Pakistan have been brought to war over Kashmir three times, a Pakistani flag in Indian-occupied Kashmir can be a very incriminating thing. Add to this the fact the flag appears on a cow, an animal considered sacred by the Hindu majority in India and is in many states illegal to kill, and we suddenly have an unusually charged concoction. With the increasing power of the Hindu far-right in Indian politics and civil society, the painted cow presented an important provocation in Srinagar on India’s Independence Day. The Indian occupying forces would detain a person, possibly kill them for doing the same, but what can they do with a cow that is at once seditious and sacred?

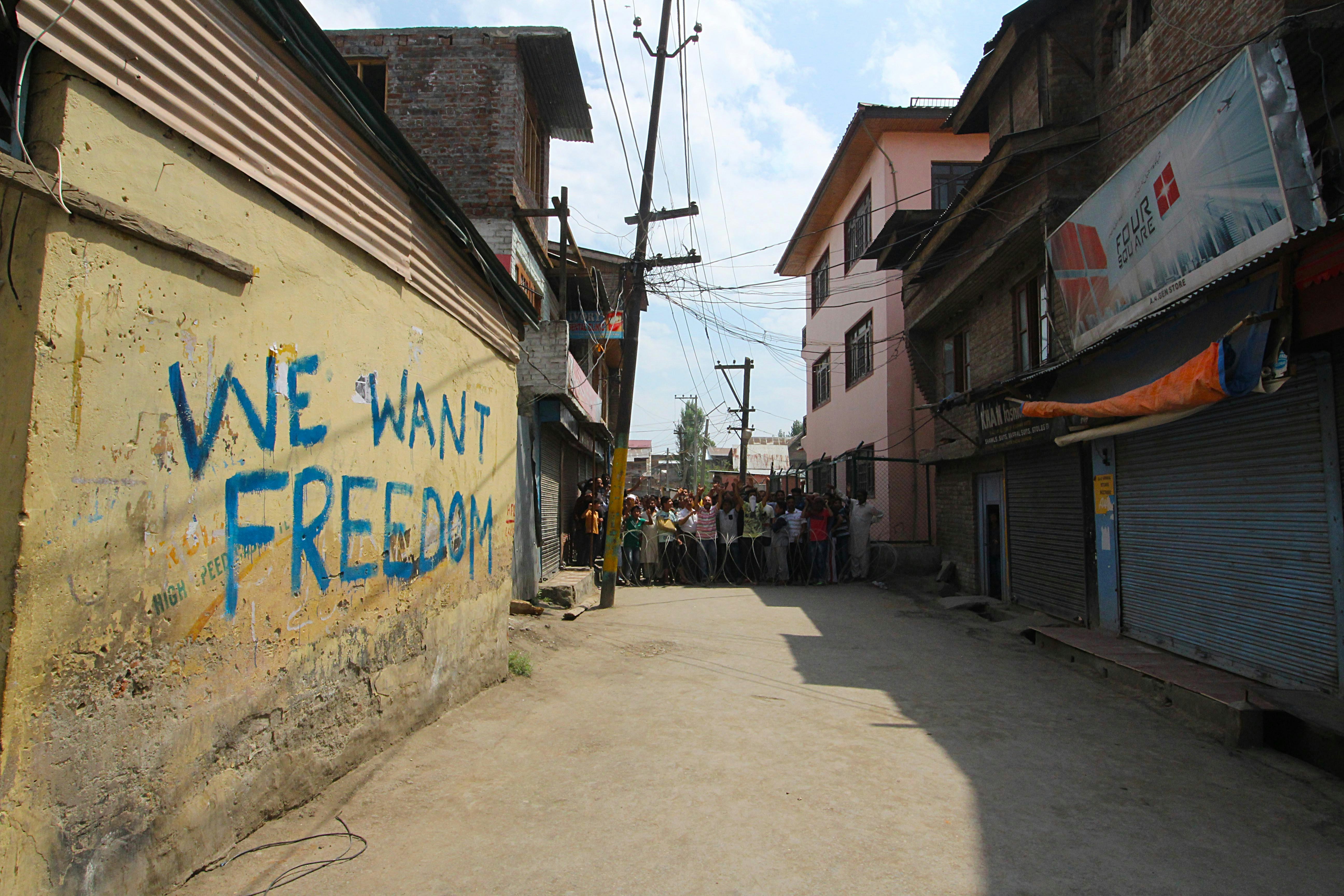

Cows aren’t the only things painted on the streets of Kashmir, walls are too. Journalist Majid Maqbool recently wrote an important article about how young people in Kashmir are using graffiti to voice their discontent with the state. Once again, the need for visibility and the act of witnessing play a central role. As a young anonymous graffiti artist remarked to Maqbool, ‘We feel the airport roads are the perfect places for us to paint graffiti and let people from the outside know what we’re witnessing here.’ But walls aren’t only the domain of the young as state authorities often try to erase the anti-state graffiti or adjust it to appear pro-state. This process means that walls are often layered in ways that reflect the ongoing dynamics of Kashmir’s struggle for freedom and its expression.

Graffiti and a protest in Kani Kadal, Srinagar; photo: Faisal Khan.

In late July an unusual poster attributed to a group identifying as the Sangbaaz (Stone Pelters) Association Jammu and Kashmir, Azad Kashmir appeared on the walls of Lal Chowk in Srinagar. On first read the poster is a chilling and confusing warning to business owners, mosques and ‘girls on scooties’. To many Kashmiris it is utterly ridiculous—stonepelters in Kashmir are united in their sentiments and action, but not organised into parties and associations. The Indian media and occupying forces used the poster to undermine the uprising by placing it under the aegis of Islamic extremism. Many Kashmiris were immediately sceptical of the poster’s provenance, supposing that in order to malign the local movement the Indian forces may have in fact manufactured it. Arif Ayaz Parrey and friends made a series of new posters mocking what they describe as the ‘original fake’. In this absurd series of mock posters, the ‘underwear agent’ requests all men in uniform to wear matching underwear; the ‘poetry connoisseur’ dictates what poetry can and can’t be; and the ‘fashion police’ order boys not to wear yellow and green for fear of looking like Delhi CNG buses! The ‘fake fakes’ are typical of the witty responses many Kashmiris have to the absurdity of life under occupation. The agricultural industry has also joined the ranks of rebellious absurdity; Kashmiri apples sold throughout India were marked with pro-freedom slogans.

IV

In December 2015 the Kashmiri Cabbage Walker began walking cabbages and other Kashmiri vegetables on the streets of Srinagar. The ongoing piece of performance art is an adaptation of the Chinese artist Han Bing’s Walking the Cabbage, which sought to challenge ideas of normalcy in public spaces in China and elsewhere. Highlighting the absurdity of what passes as normal in occupied Kashmir the Kashmiri Cabbage Walker explained:

I will be such a walker time and again to reiterate the same point: we Kashmiris are willing to normalise and accept as ‘normalcy’ walking our Kashmiri vegetables and produce on our streets, as absurd as that may seem, but we will never accept militarisation and occupation as normal, since it is far more absurd than walking haakh on a rope.

Four days before Burhan Wani died, I received a Facebook message from the Kashmiri Cabbage Walker inviting me to view a video they had recently made about torture titled Familiarizing Pain. In the video a cabbage sits on a vinyl wooden-looking floor against a white wall. The camera is shaky and the image a little blurry, leading one to assume it was recorded on a cheap phone camera. ‘Dear Cabbage…’ an American woman’s voice invites the cabbage, and in turn the viewer, to imagine the precipice of infinity through the confines of a human body and mind—first, by imagining what it is like to travel to the end of the universe; second, by imagining the pain of torture. A male hand casually slices the surface of the cabbage with a kitchen knife three times. The same hand then burns the cabbage with a cigarette twice. This is the visual track of the video, which repeats for over seven minutes, while the American woman’s narration extrapolates a detailed treaty on torture in Kashmir. Familiarizing Pain is increasingly hard to watch. The domestic banality and deep violence of the video is physically affecting. Familiarizing Pain employs an aesthetic language that has become synonymous with real videos of torture, like a video of Kashmiri boys being forced to shout Bharat Mata Ki Jai (Victory to Mother India), which has been viewed at least 70 000 times on Facebook.

There were four of us in the original Facebook message from the Kashmiri Cabbage Walker. Now only two of the four Facebook profiles remain active. Not long after Burhan Wani’s death, the Facebook accounts of many Kashmiris who spoke about the occupation of Kashmir on the social media network were disabled. A number of academics, activists, filmmakers, writers and artists (including the Kashmiri Cabbage Walker) have had their profiles disabled, some temporarily and others permanently.

In a recent article journalist Mehboob Jeelani described how Kashmiris are using Facebook to counter the Indian state’s dominant narrative, which they feel is intent on misrepresenting the conflict. Facebook provides an important bridge of communication from Kashmir to the outside world. Facebook’s censorship regarding Kashmir is not about upholding community standards; in collusion with the Indian government Facebook is playing politics in a time of war. The disabling of accounts has coincided with over 100 days of curfew in Kashmir that have seen work and school suspended, internet and phones cut, press offices raided, newspapers seized and banned, thousands of people arrested and over ninety dead.

Smart Persons Guide to Beating Facebook’s Kashmir Censorship is a playful recipe in algorithms developed by Ather Zia, whose Facebook profile was also disabled for a brief period. To avoid being censored on Facebook, Ather advises users to bury their ‘smart, alive and conscientious self in these inane news bits so that Facebook doesn’t know you care about issues that are breaking our world’. She urges people to post about Rumi, Melania Trump and kittens before and after every post about Kashmir. Ather’s guide illustrates the balancing act of visibility and invisibility that many Kashmiris face. But it also illustrates the Indian government’s desire to silence the voice of Kashmiris in order to keep its own citizens and the rest of the world in a state of ignorance in relation to its occupation of Kashmir.

Facebook provides an important bridge of communication from Kashmir to the outside world. Facebook’s censorship regarding Kashmir is not about upholding community standards; in collusion with the Indian government Facebook is playing politics in a time of war.

V

In early September an all-party delegation was sent to Kashmir from India. There was talk of engaging all ‘stakeholders’ in dialogue, and of banning the use of pellet guns. But as has come to be expected, they came and left with much fanfare and little achievement. An unidentified bruised dead body was recovered from the Jhelum River, then in quick succession a number of things happened. The noted human rights activist Khurram Parvaiz was arrested under the Public Safety Act. Two days later, as India was receiving increasing criticism for its use of violence on civilians in Kashmir, an Indian Army base in Uri was attacked by four mujahideen. Seventeen soldiers died and the focus suddenly shifted from the unrest in Kashmır to the ongoing diplomatic tussle between Pakistan and India. On 2 October the daily newspaper Kashmir Reader was banned, a pillar of rigorous and brave reporting gone. Days later, police fired tear gas and warning shots on the funeral procession of twelve-year old Junaid Ahmad who had died after being shot by a pellet gun. After 100 days of siege, when it seems things could not get any worse, they do.

In a status update on Facebook, Amjad Majid offered a telling tale:

A disturbed Kashmiri chainsmoker aspiring to be a performance artist establishes a sick personal ritual on a cloudy day in some city abroad: every time a Kashmiri is killed on the streets of Kashmir, he offers a prayer in honor of the departed and then lights up a cigarette which he then puts out on a part of his body that he can cover up, leaving a permanent circular burn-mark on his flesh. He tells his best friend that upon his death his naked body is to be photographed and exhibited for a few days. He also leaves a will asking for the same from his family and close friends that survive him. Years pass, the cigarette burns take over and spread throughout his body. The killings on the streets of Kashmir don’t stop and he dies, with his body disfigured by his maniacal manner of remembering and mourning the passing of his Kashmiri brothers and sisters. Each circular cigarette burn is a marker of the passing of others and his body becomes a map of the killing of numerous Kashmiris and a physical symbol of the pain each Kashmiri feels when we are killed on our own streets. The world is more bothered and disturbed by the disfigured sight of his burnt and scarred body on exhibit and in photographs than they are by the killing of those who died on the streets.

A contemporary parable of sorts, Amjad’s text points to the absurdity of a world more bothered by the representation of violence than by the violence itself. It also points to the complicated limits of art.

An intifada of sight is unfolding within Kashmir via the ‘streets of social media’. Through the paradigm of shahid (witness/martyr) the visual counter culture pouring forth in the year 2016 is enabling the world outside Kashmir to glimpse what Kashmir sees. View by view it is defying this blindness. Though much of this is not readily recognised as Art with a capital ‘A’. There are indeed artists contributing to the process, but more often than not it is the work that does not easily fall under the definition of art, made by people who do not necessarily think of themselves as ‘artists’ that is the most exciting, relevant and powerful.

The inaugural Srinagar Biennale is scheduled to take place in mid-October 2017, signalling another step in the formalisation of artistic discourse in Kashmir. It will be interesting to see how the biennale deals with the predicament of working as part of such a lively and contested cultural context. I do not mean the obvious quandary of orchestrating a biennale in a zone of violent conflict, but of how to actually do artistic justice to the unruly creative discourse emanating from the locale within which the biennale is situated. When I asked Inder Salim, member of the Srinagar Biennale team, he told me, ‘Rhizomatic is the key word. And slow is another. Then art, which is now everywhere.’ This sounds particularly promising.

Looking back over this year and its memes, I recognise a visual counterculture that presents a sharp take on recent history, encouraging a certain kind of constellational thinking. The memes and related social media activity could be a glorious archive, though its strength lies in its dispersed, timely and intangible nature. This places it at odds with any archival process or conventional exhibition. This instability is why it cannot be easily abolished (though at times easily disabled) because it cannot be definitively defined or contained. But as a friend reminded me, Kashmir needs azadi in reality, and not via images alone. There is a danger that, as has been the case with Palestine, Kashmir may be offered the illusory consolation of the latter while the land continues to be taken, and that people might be seduced by this offer. Thinking through this dilemma, the writing of Kashmiri anthropologist Mohammad Junaid sums it up beautifully:

I have heard people sneer at calls to turn our power or potentia into aesthetic practices. Rightly sometimes—art is neither political action nor a substitute to it; however, they complement each other. Not all aesthetic forms are practices of truth, of course…Art, music, writing, however, open spaces within the dark, spaces to which the occupation remains blind. Art can also open those spaces that might otherwise remain invisible to the resistance. This space is azadi. It expands. It sutures the wounds of trauma. Yet, it never forgets. It preserves memory as a source of strength, rather than as a corrosive pain. It is a secret language that remains incomprehensible to the occupier.

About the contributor

Alana Hunt lives on Miriwoong country in the north-west of Australia and has spent lots of time in South Asia, and more specifically Kashmir. These places shape her artworks and relationships.