Cities, neighbourhoods, spaces: conversations with Anthony Yung, Lucas Ihlein and Trevor Yeung

Minerva Inwald

with Anthony Yung, Lucas Ihlein and Trevor Yeung

Observation Society from the street during the install of Sea Pearl White Cloud, May 2016; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Over two weeks spanning late May and early June 2016, Minerva Inwald traveled to Guangzhou, China, to experience the lead up to Sea Pearl White Cloud 海珠白雲, a collaborative two-stage exhibition project produced by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and local independent contemporary art space, Observation Society, that saw presentations in Guangzhou and Sydney. Sea Pearl White Cloud presented new works by Australian artist Lucas Ihlein and Hong Kong-based artist Trevor Yeung that are informed by questions of temporality, exchange and poetics while reflecting on the urban condition in the twenty-first century.

Minerva was the recipient of the inaugural 4A Emerging Writer’s Project, an initiative that seeks to provide opportunities for Australian writers interested in contemporary art and culture to undertake fieldwork in Asia, with publication outcomes supported by 4A Papers and Art Monthly Australasia. Having published a short essay on Sea Pearl White Cloud in Art Monthly Australasia’s September issue, what follows below is an edited excerpt of conversations between Minerva and Observation Society co-founder and director, Anthony Yung, along with Lucas Ihlein and Trevor Yeung, undertaken in July on the eve of the opening of the exhibition at 4A.

— Editor

We wanted people from the neighbourhood to walk by and see the space, to be able to look through the glass, even if they don’t come in. We liked that feeling of subtle interaction with the community.

Minerva Inwald: Why did you choose to establish Observation Society (OS)?

Anthony Yung: Basically, we decided to do it for fun. Our motivation was very simple and direct. We were not happy about the exhibitions being done by many other art institutions and organisations, so we wanted to do something where we could make the decisions. So we started a space. The space is in Guangzhou, firstly, and most importantly, because it is cheap. It was very cheap when we first started in 2009, and it is still quite cheap compared to Shanghai or Hong Kong. Secondly, we liked the local art community a lot. It is non-commercial, people are very relaxed, and artists are very free in terms of what they do. Although they cannot earn money by making art, they can basically do whatever they want, so they don’t feel any pressure from so-called ‘art circles’ and all that. So we think Guangzhou is perfect.

Minerva Inwald: What is the relationship between art exhibition spaces and artistic communities? What is the importance of an exhibition space like OS to the Guangzhou art community?

Anthony Yung: Let me answer the question in this way: we thought a lot about whether we wanted to have a stable space; whether we wanted to rent a space and run it, because that is costly; or asked ourselves if we wanted to do pop up exhibitions, so it would be cheaper. We thought a lot about that—our final decision was that we wanted a space because we wanted a long-term form for artistic activity. We wanted OS to be stable, and we wanted it to create a kind of standard so that each artist can use the same space differently. We wanted the space to be a constant in the formula. The good thing about having the space is that you have a boundary or a framework that different people can work with. It’s very interesting to see how different artists turn the space into very different things. And the space has become something that we love, a space that we are familiar with. Here I should say that I mean space in both a physical and a psychological sense. It’s a place that people go to whenever we have exhibitions, and artists and people from the community come together and talk. I think the space and the community are closely related to one another.

Minerva Inwald: OS is located in a residential neighbourhood in Guangzhou’s Haizhu district. Can you explain why you chose this location? How do you see this area in the wider landscape of the city?

Anthony Yung: This was actually the area that we hung out in, even before we had OS, because the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Libreria Borges, and the old Vitamin Creative Space were nearby. It was the area where we hung out, as simple as that. Whenever I came to Guangzhou I went to that part of Haizhu to have lunch, to have drinks. That was the area where most of the interesting things were happening. Our feelings changed a little bit when Vitamin Creative Space moved further out from the city centre, and when the Guangdong Times Museum opened in the city’s north. Now you have to travel around the city quite a bit to see art. But it’s still a very natural space for us. In terms of having OS in the residential neighbourhood, it’s because we wanted to be around people. We did not want to hire a space that was hidden away in a building. We wanted people from the neighbourhood to walk by and see the space, to be able to look through the glass, even if they don’t come in. We liked that feeling of subtle interaction with the community.

Haizhu looking towards Observation Society’s neighbourhood, as viewed from the rooftop of the nearby Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, May 2016; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Minerva Inwald: Through your work with Asia Art Archive, you produced the documentary From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng: Cantonese Contemporary Art in the 1980s, which talked about the idea of a ‘southern art attitude’. Do you think that still exists in China now? Does Guangzhou produce a particular type of artist?

Anthony Yung: There not a huge difference between the 1980s and now, but ‘southern-ness’ is still a very important thing that is rooted very deeply in Cantonese culture, something that is different from the rest of China, especially from the political centre in the north. I think this is what makes Guangzhou such a great place for contemporary art, because people think quite differently. People are allowed to think very differently, function very differently, and live very differently than in other Chinese cities. I am not only comparing the south and the north—I am talking about the fact that among people in the south, and among people in Guangzhou, there is a kind of diversity. Guangzhou has a tolerance that allows people to do different things. ‘Southern-ness’ is something the whole world is talking about. The Documenta coming up is also talking about this idea of the ‘south’. It is quite obvious in the Chinese context that Guangdong is the typical realisation of the concept of the ‘south’.

Minerva Inwald: In the lead up to the opening of Sea Pearl White Cloud at OS there were visits from the police. Do you ever wonder about the longevity of OS?

Anthony Yung: Honestly speaking, I do not think there are problems. If we don’t go looking for problems then I think we will be OK. We are very small scale; the police are busy enough. This was a special case because the Lord Mayor of Sydney attended, and that is why they paid attention to us. We don’t intentionally do things that are politically provocative. It’s not like we are scared, we just prefer not to seek attention in this way. There are plenty of ways to say what we say, ways that are subtle enough, and clear enough.

Anthony Yung at the opening of Sea Pearl White Cloud, Observation Society, June 2016; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore (centre), and Deputy Mayor, Robert Kok (centre rear), with City of Sydney associates, Guangzhou Municipality representative and local artists outside Observation Society at the opening of Sea Pearl White Cloud, June 2016; photo courtesy City of Sydney.

Minerva Inwald: Are there any parameters that apply to all exhibitions at OS?

Anthony Yung: Our main thing is that we limit the expenses of each exhibition to RMB 10 000. Even if the artist wants to spend more money on the exhibition at their own expense, we don’t encourage that. In terms of making art, we do not think that more money is more helpful. That is the main parameter. The other parameters are quite flexible; we mainly work with young artists from the region, we mainly put on solo exhibitions, but these are not rules. They’re changeable, so long as it is something that is interesting.

Minerva Inwald: Does OS have a ‘curator’, or do you leave decisions about the exhibition up to the artist?

Anthony Yung: This is an interesting question. We pay a lot of attention to discussing not only the specific exhibition proposal with the artist, but also talking to the artist about art, philosophy, or anything else that is interesting. We treasure these conversations because we treasure mutual understanding. This is our kind of curatorial involvement, but it is not curatorial involvement in a traditional sense. So we don’t just talk about the exhibition, we talk about everything, because by fully understanding artists’ motivations and ways of thinking we can find a way to really convey or express their artistic ideals.

We do not have a curator—we never call ourselves curators, and we do not have a curator responsible for individual exhibitions, yet at the same time we pay a lot of attention to talking to each other, which is a kind of curatorial model. We do this because curatorship in the Chinese context is very weak. Museums and institutions in China do not have curators, they do not have a job called ‘curator’. They have people who organise exhibitions, they have people who do research, but there is no specific definition of the function of a curator in making an exhibition. So there are many people who call themselves ‘curators’, but they might be people who look for money, or write the catalogue, or maybe they own the space. So I think it is quite confusing to call yourself a ‘curator’ in China.

If I may take your case for instance, Minerva, you undertake research on the National Art Museum of China, so you know they never had a ‘curator’. It is different from the western context, and that is why we avoid the confusion of calling ourselves ‘curators’, or hiring curators to be responsible for exhibitions. We would rather be vague about it. It also allows us a certain flexibility if we do not call ourselves curators, because then it does not matter—we can be free from anticipation and definition.

Minerva Inwald: Does OS approach artists or do they approach you? How long do discussions with the artists typically go on before the exhibition opens?

Anthony Yung: In ninety percent of cases, we approach artists. The period of discussion? It varies. Sometimes it takes months, at the shortest, maybe half a year. But it can also take three or four years. We keep it very flexible because we can change the opening and the exhibition dates in any way we want. So usually it is a very long discussion.

Minerva Inwald: Is the Sea Pearl White Cloud project the first time OS has collaborated with another organisation?

Anthony Yung: Collaborating with 4A is our first time working with another organisation. It is a new experience for us.

Minerva Inwald: When you embarked on the collaborative project with 4A, were there particular outcomes that you were pursuing? What made the collaboration attractive?

Anthony Yung: When 4A first approached me, I invited them to decide which artists would do the project. I asked 4A to select one artist that OS had worked with, just to make sure that this is someone we are familiar with, and they recommended Trevor Yeung alongside Lucas Ihlein. I thought it was a very good choice because the two of them have some things common, and some things that are very different. This is the best scenario in collaborations; you need two people that have common ground, but are also extremely different, so that there is conflict and excitement between the two of them. We had worked with Trevor before, so he already understood the philosophy of OS, and he understood Guangzhou as a city and as a community. I wanted Lucas to spend time in Guangzhou to really understand the community, to understand the lifestyle, to see real things about Guangzhou, instead of just touring around, seeing things that are exotic. I wanted to avoid this obvious problem. We discovered that Lucas had come to Guangzhou many years ago, I think it was even in the nineties, and at that time he met some of the best artists from Guangzhou, they showed him around, and told him about their works. That relationship underlines the partnership.

Trevor Yeung, Encyclopedia (installation view), Observation Society, 2013; photo courtesy the artist and Observation Society.

Minerva Inwald: The exhibition project is part of the thirtieth anniversary celebrations of Sydney and Guangzhou’s sister-city relationship. Does the sister-city relationship mean anything for you?

Anthony Yung: It’s actually really funny, because we never realised that there was a sister-city relationship! Living in Sydney, you did not know Sydney had anything to do with Guangzhou, right? We didn’t want the project to be so directly about the two cities, or to express something simplistic about what Guangzhou is like, what Sydney is like, etc. Keeping with OS’s philosophy, we wanted to reduce everything to individuals. Lucas has lived in Sydney, he has spent a lot of time in Sydney, and of course he can represent things about Sydney, or Australia. We believe as long as Lucas can do whatever he wants to do, he will ‘represent’ Sydney in that he can represent the sensibility of the city. The same for Trevor. So we built a relationship, instead of talking about Sydney and Guangzhou.

For me, collaborating with 4A was the most important thing, because we think that 4A is very similar to OS in terms of its original motivation and history, and in terms of its structure. 4A has a much longer history, but we have the same spirit, and there are a lot of other places in Asia that have the same spirit as 4A and OS. I am really dedicated to OS doing more collaborative projects in the future. I think it will be very helpful, and create a good networking energy, by sharing expertise, curatorial ideas, and even resources.

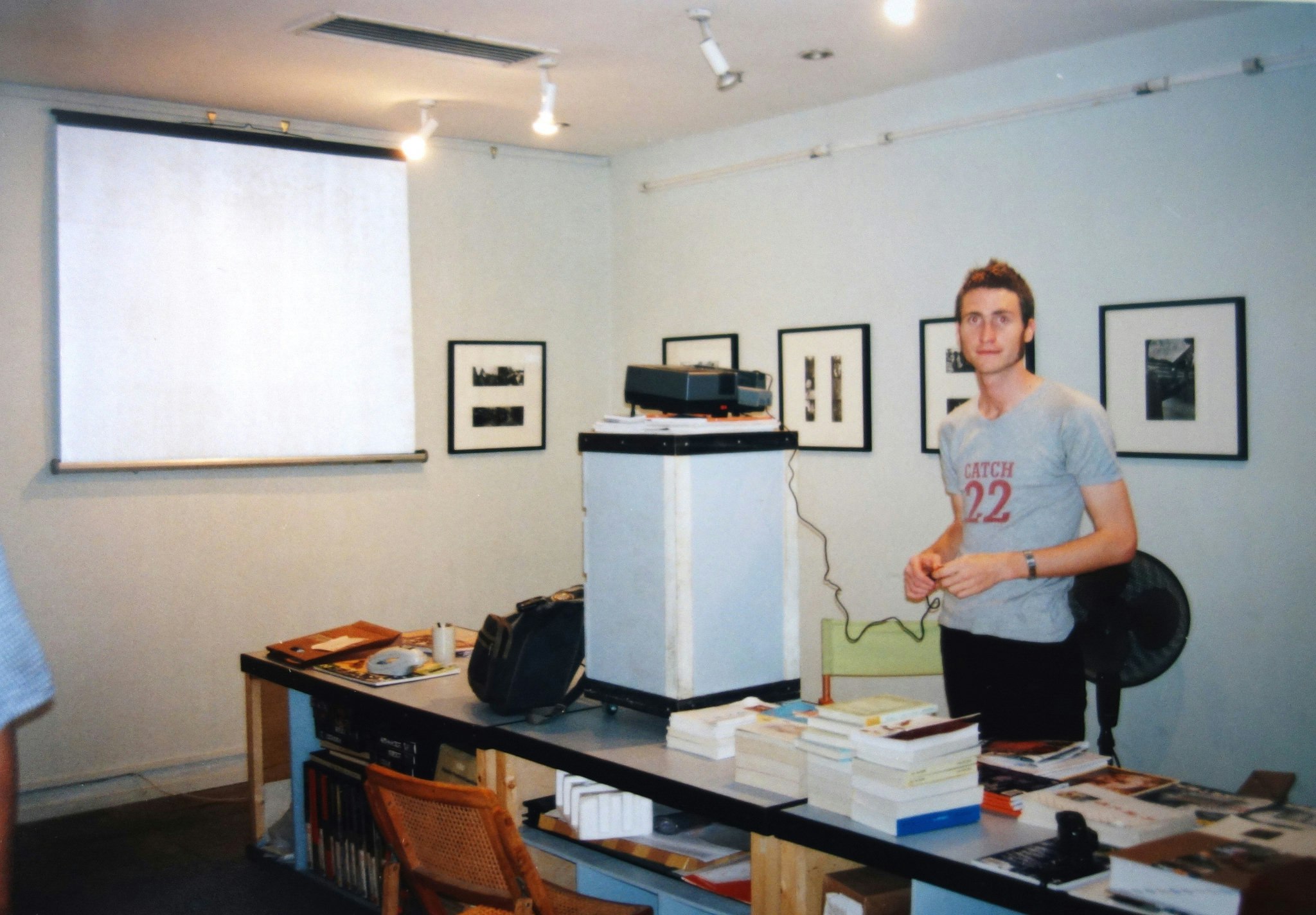

Lucas Ihlein at Libreria Borges, Guangzhou, 1999; photo courtesy the artist.

Bridge under construction, Guangzhou, 1999; photo: Lucas Ihlein.

Minerva Inwald: How did you get involved in the project, and had you been to Guangzhou before?

Lucas Ihlein: I had been to Guangzhou in 1999 when I was doing a project as part of the Artists Regional Exchange program in Hong Kong. My friend Jeremy Hiah, who is an artist from Singapore, suggested that we travel across the border to see ‘Canton’, as he called it, and I was really excited about that idea, so I booked my trip. He eventually cancelled, so I went on my own and had an amazing time. I had the phone number of Xu Tan, one of the artists from the Big Tail Elephant Group, and all the members of that group took care of me that week, taking me around and showing me things, organising for me to do a slideshow at the Libreria Borges bookshop that Chen Tong was running. At the time it seemed to me that they were very keen on visits from international artists, that contact with the outside world beyond the Chinese border was perhaps minimal for Guangzhou contemporary artists at that stage. So that was a really amazing experience and I always wanted to go back. When 4A contacted me and asked if I would like to be involved in this project linking Sydney and Guangzhou, I obviously thought it would be a wonderful opportunity for rediscovering the place, deepening connections to it, and seeing what changes had happened there.

Minerva Inwald: Had Guangzhou changed a lot since 1999?

Lucas Ihlein: It was almost a completely different city. I found it difficult to see the things that I had experienced when I was there sixteen years before, because it had transformed so much.

Minerva Inwald: When you started the project were you thinking about the Guangzhou that you visited in 1999, was that the place you were planning on encountering?

Lucas Ihlein: I didn’t have any particular plans. Even when I visited in 1999, there were no preparations, I just went. I was like a piece of driftwood floating around, just allowing whatever to happen. I certainly had no recollection of the fact that Guangzhou was built on a delta, and at that time I was unaware of all of the industrial and agricultural issues. The main impression I remember is something that one of the members of the Big Tail Elephant Group said to me, which was that their art was very different from the work of contemporary artists from Beijing, who were very concerned with national identity. There was a lot of work at that time coming out of Beijing which revisited the cult of Mao through parody. Whereas the work of the Big Tail Elephant Group was about small acts of everyday resistance in Guangzhou. They had this expression: ‘the mountains are high and the emperor is far away.’ It is not as if they did not feel as strongly as the artists from Beijing about the problems with Chinese national identity and government rule, it was just that because the seat of power was so far away, they did not have to deal with it, it was not in their face all the time. In a way, I felt like in the late nineties the art that was being made in Guangzhou was closer to an ‘international contemporary art’ idiom, it did not necessarily always look like ‘Chinese contemporary art’.

A creek in Haizhu, April 2016; photo: Lucas Ihlein.

Minerva Inwald: Your work for the project evolved out of creek walks in Guangzhou, and also later on in the project, your visit to a rice farm in Guangdong province. How does fieldwork relate to your art making practice?

Lucas Ihlein: I have been doing walking as an art practice for a long time now, I guess since around 2005 or something like that. Those were the first times I can remember actively using walking as a kind of method, not just as a form of exercise or a way of getting from one place to another pragmatically, but as an open exploration where the walk is a performative, aesthetic activity in its own right. Obviously it has an ambiguity about it because it is not evident to other people around you that you are engaging in an art activity, you just look like you are going for a walk. But sometimes, like if you go for a walk in a small country town in Western Australia, which I did in 2005, people are very curious because usually that means your car has broken down. So sometimes walking can really stick out like a sore thumb, and sometimes it can be very inconspicuous.

Where I live down in Wollongong, I have been involved with a project that has been running for a few years now, and will probably go for many more years, called Walking Upstream: Waterways of the Illawarra, a collaboration with artists Brogan Bunt and Kim Williams. Walking Upstream involves the very simple act of starting at the sea and walking along the creek line until you cannot walk any longer, usually because of property, fences, a highway or a railway or something. Sometimes we get high up enough in the escarpment that creek sort of disappears, it seeps from underneath the hill. It is a very gentle way of getting to know the local area where we live. The creeks are like a character in the landscape in Wollongong, whereas in Sydney many of them have been paved over and you would not even know that they were there in the past. So I guess I took that with me, subliminally, to Guangzhou. There is one little creek near OS, and when I zoomed back from that I realised that the whole place was crisscrossed with these tiny little waterways, and that is what set me going on this project around the delta and all the watery stuff to do with that.

Creek walk in the Illawarra region south of Sydney with Sharon Concannon, Kim Williams and Trevor Yeung, July 2016; photo: Lucas Ihlein.

Minerva Inwald: Your work Guangzhou Delta Haiku (Pearl River Delta Flood Maps) (2016) uses different registers, prints, haiku, animation, text, to convey information about sea level rise. How each of these forms work together to communicate ideas?

Lucas Ihlein: I love maps. I love making maps, and I love the power that a map gives you to have a conversation around an issue that might be difficult to talk about. They have a persuasive power, like a story, but in a different way, because of the ability of a map to assemble a whole bunch of information visually in one place at one time. For example, the five-metre sea level rise map of the Pearl River Delta I created for Guangzhou Delta Haiku almost makes a case for the fact that it has already happened. That is the ridiculous power a map has, even when it is a completely fictional made up entity. With a lot of the work that I do I try to be sincere to the levels of information people need in order to access the artefacts in some way. I am not against mystery and ambiguity and multiple interpretations, but a lot of the time when I go to see art exhibitions I am aware of the fact that the artist really wants you to know a whole bunch of information in order to access the work, and you hear about it either through a didactic panel which is separate from the work, or through some kind of story that somebody tells you when you are standing there, maybe the gallery attendant. However, a lot of the time these extra pieces of information are externalised from the artwork itself. It has been an interest of mine for ages to try and work out how to bring the bits of information that you need into the body of the artwork itself. I think some artists would find that overly didactic, because they would think the work should somehow stand on its own feet without that ‘extra’ information. I think if we are being honest, a lot of the time when you hear the stories that are external to the artwork they do help you open up another world of appreciation for the work. So it has been a bit of an experiment to bring those things in.

Haiku is another thing that I have been experimenting with recently, using that brief poetic form to distil something, another way of crystallising something. In Guangzhou Delta Haiku those three elements are able to push against each other within the composition of the overall work. That is the idea anyway.

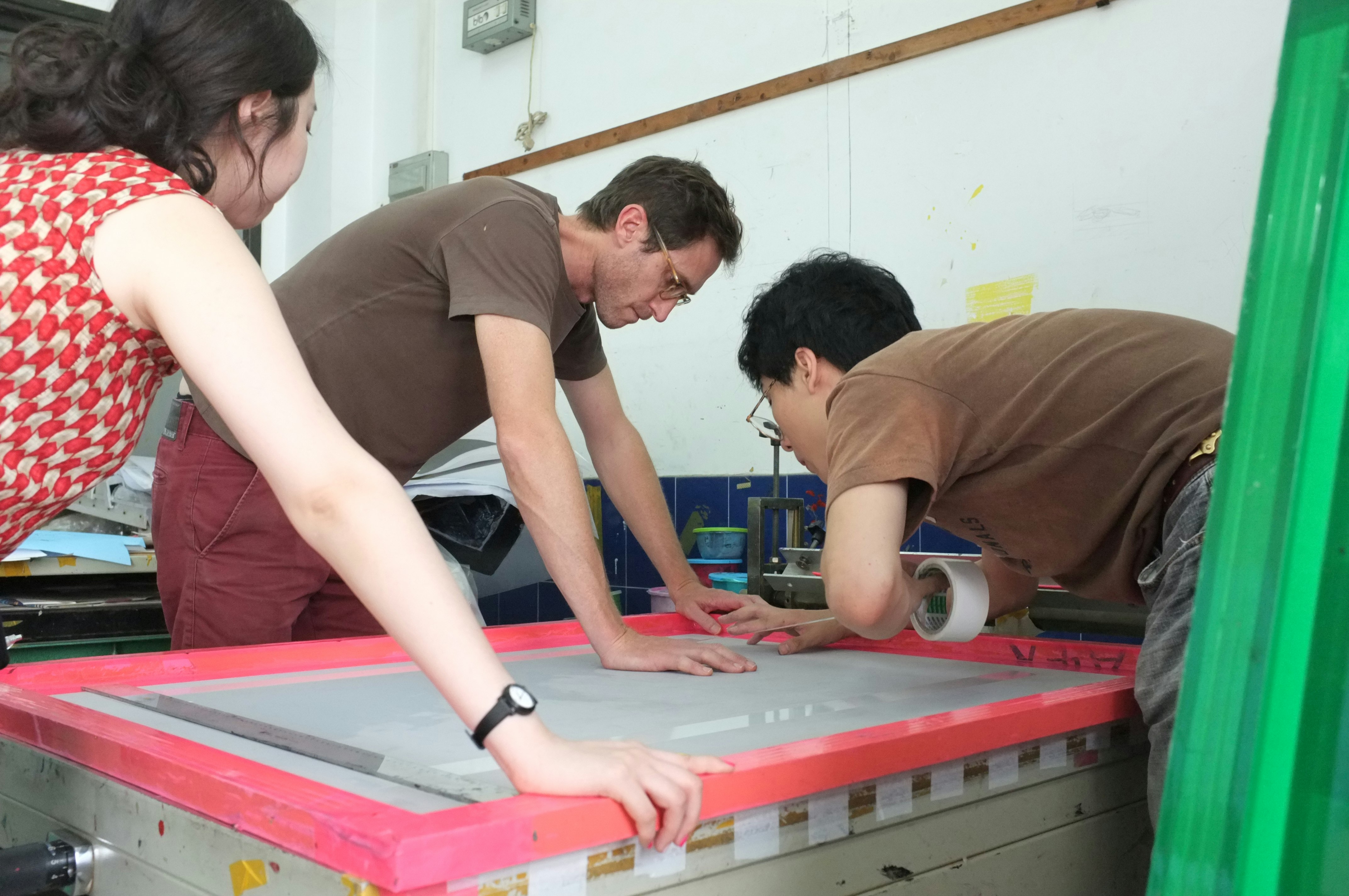

Lucas Ihlein screen printing with with Hanting Feng (Observation Society coordinator and Sea Pearl White Cloud co-producer) and Liang Yonghao (artist and postgraduate student) at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, May 2016; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Minerva Inwald: What potential does the gallery space have to communicate information that might otherwise be presented in complex scientific language?

Lucas Ihlein: For me, the art gallery provides a ritualised occasion. I do not think that it is inherently superior in any way to a scientific journal, a blog, a three-minute YouTube video, a tweet, or any other form. These are just social communicative forms, and each is useful in its own way for a different depth of communication. There are also levels of affect. If you are sitting in a dark cinema, for example, you have made an appointment with yourself for a couple of hours to turn yourself over, to put yourself in the hands of the filmmaker. The gallery is just another one of those kinds of forms, which creates an occasion. So for example, here in Guangzhou it creates an occasion for the Deputy Mayor of Sydney, in particular, to come down and start to form a relationship with the people who run the gallery. Those kinds of localised social relations are really important, and they are lubricated by the fact that you have artwork which addresses a certain subject matter that everybody agrees they want to talk about. It also creates the opportunity for media articles, radio shows, etc. so that these ideas can get out into the public sphere as well.

Minerva Inwald: What is value of moving the project from one city to another, from one space to another?

Lucas Ihlein: I guess it is partly about presentational contexts. When you are an artist working in a particular place, like an artist going from Australia to China, and you make some work that responds to that particular local context, and then you present it within that context, it is like a kind of recycling or feedback loop within the environment it was created, but it is understood by local audiences as the reflections of an outsider. When you bring it back and present it in Australia, even if it is exactly the same material, it is received differently. Here in Australia, it is almost like a kind of mild cultural tourism that allows people here to have access to another world they are not part of. So you actually create totally different artworks from the same material depending on the local cultural and language context.

Minerva Inwald: So for you it is more a question of how the audience will receive the work in each city, rather than the experience of the artist in each city.

Lucas Ihlein: The artist’s experience is also really different. Because I’ve been living in Sydney since 1996 and have a long history here, this context is really familiar to me. It’s much more difficult for a local artist to see their own environment with fresh eyes. In the past I have used different approaches to gain fresh eyes on the ‘local’, but that was not my particular focus in this project, it was more about how to mediate the materials that I had. As time goes on, I have become much slower in the way that I work, and you have to make choices. Was I going to put aside all of the stuff I did in China and focus on trying to explore something locally with fresh eyes, which is a whole project in itself, or was I going to turn again to that material from China and see what it said to me now that I had returned? In this case I chose to do the latter, but that is no reason to say that it is a better way of doing things.

Minerva Inwald: The idea of the exhibition being a ‘mild form of cultural tourism’ is interesting to me, that you brought the material from Guangzhou to a Sydney audience, rather than making new work about Sydney.

Lucas Ihlein: It is really just a question of limited time and space. If we kept going with this project for another month, there would have been more opportunity for that as well. I think the good thing about Sea Pearl White Cloud is that it was an experiment, not a curatorial project that says, ‘I like this artist, I like this artist, these are the works I like by you, these are the works I like by you, let’s put them together.’ It is very open ended, and there is the possibility of something working or not working.

Minerva Inwald: And the work continues on your blog, guangzhou-delta-haiku.net

Lucas Ihlein: Yes. The project also continues with my collaboration with a rice farmer called Tim, who is going to come and speak at our public program event, Talking About Rice While Eating Rice. Those events are also part of my work. So yeah, it carries on.

Trevor Yeung with Observation Society handlers installing a component of his work, The Saddest Sunrise (Byron Bay) (2016), May 2016; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Minerva Inwald: How did you get involved in Sea Pearl White Cloud?

Trevor Yeung: Three years ago I got an invitation from Anthony Yung to exhibit at OS. We developed a very close relationship. OS builds strong connections between the space, the curator, and the artist. Later, Anthony told me that he would be collaborating with 4A, and I said OK, let’s talk. I found out I would be collaborating with another artist, Lucas Ihlein. Before meeting Lucas, I had my personal perspective on the project, thinking about the relationship between the two cities as a metaphor. In the beginning, because we did not know each other, it felt like blind dating. I tried my best to find out about Lucas before we met each other in Guangzhou, then we spent one week together in the city a few months before the exhibition was scheduled.

Minerva Inwald: How was working on a two-stage, international collaboration different from your normal practice?

Trevor Yeung: I think it was very difficult. First, we are two artists with different backgrounds, with different cultural experiences, who were then put into the same context. Two artists, first working in Guangzhou, then in Sydney—it was kind of a strange. I think that it was easier for me because I know a little bit about Guangzhou, and was in fact born in Guangdong. But the work was also based on the experiences that Lucas and I had when we were doing site research toegther. That was very different from what I normally do. Usually I have some idea or something that I want to talk about, then I will start to work on things before the project happens. But this was more residency-ish; it was very open minded, we could choose whatever we really wanted to focus on. But at the same time because it was a collaboration, I wanted to find a balance. We shared the space, and the ideas, and we did things together, like in Guangzhou we went to a village and to the goldfish market together. I went to Wollongong where Lucas lives and did a creek walk, which is his ongoing project. Basically we exchanged lots of information and we now understand each other quite well. Not just aesthetically, as artists, but also as human beings. When you do a project like this it is not just about executing an exhibition, it is about how to build up the whole project together.

River near Observation Society, Haizhu, May 2016; photo: Minerva Inwald.

Minerva Inwald: How did it moving from OS in Guangzhou to 4A in Sydney affect the project?

Trevor Yeung: I would say that I am very sensitive to observing my surroundings. So when I go to a different city, when I go to Guangzhou and then to Sydney soon after, I am doing the same thing—observing—so for me it is not a big difficulty. Before I go, I find information on the internet, then when I arrive I talk to people. Locals tell me facts or stories related to their own experience, and sometimes that confirms the things that you find on the internet. The spatial difference is also very interesting for me. At OS there is a big window that the audience and public can look through and see the whole space. At 4A there are two floors, and the sun comes in through the windows and changes environment of the exhibition space a lot, which I think is so interesting.

In both my practice and my personality, I am always curious about systems. Once you know the system you can deal with things more easily. One of the works at 4A, The Pond of Outsiders (2016), is like me. I am an outsider in the space and as an outsider, I have to try and get involved and understand things. In Sydney I had to build lots of things, and now I know if I want to do that, then I have to go to Bunnings! When you know the system, where you can get the things that you want, then you can get involved and do the things that you wanted to do.

Minerva Inwald: Your work has a real sensitivity to the gallery as an environment. In what ways does introducing living things like fish or plants into the gallery space require changing the gallery, and in what sense do the living things adapt to the gallery? Does it go both ways?

Trevor Yeung: I think goes both ways. Take The Pond of Outsiders as an example. The fish have to adapt to the pond size, the temperature, and the people who feed them—the whole aquatic system. At the same time, the people from the gallery, they have to learn how to deal with the fish. The space also has to adapt to the fish pond. You never know how much installing a pond will affect the space. A fish tank is heavy; maybe the pond lining will break and water will leak out, damaging the floor. It is a balance between the material I use to protect the gallery, and how the people who work in the gallery protect the fish. Both work together.

Trevor Yeung at Guangzhou Huadiwan Fish and Aquarium Market, Liwan District, May 2016; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Minerva Inwald: Your work The Saddest Sunrise (Byron Bay) (2016) uses light to degrade the photographic image, exposing the conservation practices that go on in art galleries to preserve art objects.

Trevor Yeung: When I was initially planning my work, The Saddest Sunrise, I didn’t really think about it from a gallery perspective. I thought about the medium of photography first; how photographs are protected, how they are sensitive to light. People working with art always want to keep artworks away from UV light, because it can destroy lots of surfaces and materials. I wanted to make something that had the feeling of old memories. Just like photographs, the sunset is something people want to preserve, but maybe it is not worth preserving. When I was sent the floorplan for 4A, I noticed that they always put artworks on the far right hand side of one of the walls. I was curious about this, and I found out that it is because part of the wall gets too much sunlight, and because it is a heritage building they cannot change the position of the windows. I thought that I could use that, so I placed the photograph next to the window so it is totally effected.

Minerva Inwald: You also made a work for 4A with magnolia trees, Waiting for Spring (2016), which has to be next to the window to get natural light.

Trevor Yeung: My first impression when I arrived at 4A was that there was lots of windows and lots of sunlight. The sun coming in from outside changes the lighting system inside. Two years ago I was trying to learn about the greenhouse system. At the beginning of the greenhouse system, they developed something called an ‘orangery’, which is basically a kind of indoor space but with large windows. Versailles, the palace, had an orangery garden. In the winter they would move all of the orange trees into the orangery. This meant that during winter people could preserve the tropical plants in non-tropical areas, just like Europe where the winter is super cold. When I stood in the windows at 4A, I was thinking of the feeling of looking outside but not being able to go outside, only being able to look out. I put the plants in this position, so that when the audience comes in they feel the connection with the indoor space, the plants, but also the outdoor space. When I went to the gardening shop I found the magnolia x alba [a variety of magnolia champaca, or champak]. That was super amazing! I did not think I would find that plant in Australia.

In Guangzhou I did a work, Behind Ear, White Champak (2016) that is a small drawing of two champak flowers tied together. This is a very intimate gesture. In the old times people in south China used this flower as a natural perfume by putting it behind their ears, or carrying it as a charm on their body for its fragrance. I thought of this work in Guangzhou, because where OS is located there are champak trees at either end of the residential complex, and it was the right season and the trees were blossoming. This was a nice fragment for me, they look like a couple, and although they are far away, but they have something connecting them together. That is why the flowers are tied together in Behind Ear, White Champak. But they are also forced to be together, because normally they are apart. Actually it is like the relationship between me and Lucas, stuck together for this exhibition. I try not to romanticise these kinds of things because it is a collaboration, but you can feel being tied together.

Trevor Yeung, Guangzhou, May 2016; photo: Minerva Inwald.

Minerva Inwald: When you choose a species of fish or type of plant for your work, do you think within their ‘natural’ behaviours you are looking for human, emotional behaviours?

Trevor Yeung: I am interested in aquariums and plants, so I know the characteristics of particular fish and particular plants. The behaviour of the fish is a really important part of the artwork. The white cloud mountain minnow always swims in a group. As an outsider, you always want to find the company of other outsiders, adjusting to a new environment together, building up a community. The white cloud mountain minnow is originally from Guangzhou, and it also have this group behaviour, so I used this type of fish to talk about being an outsider, or in Guangzhou, to talk about being an insider. Not all other fish have this habit of swimming together or living as a group. Say I used goldfish for The Pond of Outsiders, which is a kind lucky fish in China, it would not make sense.

Minerva Inwald: Did you use the same species of fish for your work White Cloud Mountain Minnow (2016), shown in Guangzhou, and The Pond of Outsiders, exhibited in Sydney?

Trevor Yeung: Yes, the same type of fish, the same species. They are originally from China, but the ones I bought Guangzhou were Chinese-Chinese, and the ones I bought at the aquarium in Sydney are Australian-Chinese. These fish were farmed in Australia, but the species is originally from China, so that means they are immigrants. During my time in Sydney we had dinner in Hurstville one night and I heard that over fifty percent of the people living in Hurstville have Chinese ancestry; it is in fact the largest Chinese community here in Sydney. I think that it is kind of amazing how people build up their own community. In Hurstville you can feel that the whole atmosphere is Chinese, but the smell is not Chinese. The urban planning, the streets, the houses, and the buildings are not Chinese. It is interesting how people adapt. Just like me. I might come here for exhibition, or I might even move here one day, and that is something I will face the same as the fish in the gallery.

Minerva Inwald: Can you explain the colour ‘no worries blue’ that you used in your works Fresh Cut Lantana (2016) and Clouds of Mixy (2016) in Sydney?

Trevor Yeung: ‘No worries’ is my understanding or impression of Australians as really easy going. There are two aspects to these works. One aspect is how restricted things are in Australia. It is prohibited to bring fruits and other foods into Australia. Australia tries to stop everything because of experiences in the past, when lots of things that were done that harmed the land, like bringing in rabbits, cane toads, and lantana. These things are restricted because people have been hurt. Just like in a romantic relationship, someone gets seriously hurt and they set up borders and they find it difficult to love again because they worry about getting hurt. So that is why there are lots of rules, and people follow these regulations. Somehow I found this very strange because the British settlers were themselves outsiders to Australia. They became insiders. When I found out all about the imported pests, like the rabbits, I thought it was the same kind of situation. I do not know if this is a really sensitive for topic for the people who live here as Australians. I think it is a contradiction and also ambiguous so I am not sure how to talk about it.

At the same time, the climate here makes people very comfortable, and I feel that it is very easy to have a positive mindset. People who come to Australia to do research, or who have lived here, always mention the sky. The first time I went to Australia was to see the sky. In Hong Kong the sky is so small. The sky in Australia is so big, and the intensity of the blue is amazing. Basically half of what you see is blue. So when Lucas and the rest of you say ‘no worries’, I think of this really blue colour, a colour that makes people feel no worries. So that is how I thought of ‘no worries blue’, but it is also connected to the rabbits.

Trevor Yeung picking fresh lantana near Botany Bay, Sydney, July 2016; photo: Minerva Inwald.

Sea Pearl White Cloud 海珠白雲 was presented at Observation Society, Guangzhou, from 1 June – 24 July 2016. A second iteration of the exhibition was presented in Sydney at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art from 30 July – 24 September 2016. Sea Pearl White Cloud was supported by the City of Sydney with Observation Society’s exhibition opening being part of the official cultural program of the City of Sydney and Guangzhou Municipal government’s civic celebrations as part the 30th anniversary of their sister-city relationship. 4A Emerging Writer’s Project is supported by Art Monthly Australasia.

About the contributor

Minerva Inwald is a current PhD candidate in the Department of History, University of Sydney, whose research focuses on the history of the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) between 1958 and 1989.