Developing exposure: working with Dacchi Dang

Harriet Reid

Dacchi Dang, Dacchi Dang: An Omen Near and Far (performance view), exhibition opening, 8 June 2017, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. ; photo: Document Photography, courtesy 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and the artist.

Dacchi Dang is not an unfamiliar face to 4A.

He is, one must state from the outset, a founding member of the organisation, helping initiate, support and shape 4A’s objectives that remain at its core today: not least, its core mission to develop the dynamic relationship between Australia and the wider Asia region through contemporary art. He has held three solo exhibitions at the gallery since 1997 (5×5, 1997; The Boat, 2001; and Liminal, 2006), and participated in one of 4A’s most ambitious projects, Edge of Elsewhere (2010–2012), a partnership with Campbelltown Arts Centre that saw exhibition outcomes over three years as part of Sydney Festival. In June, 4A presented the first survey show of his career, Dacchi Dang: An Omen Near and Far. I began working at 4A as a gallery assistant in late 2015, and within weeks of joining the team I was aware that Dacchi was held in high esteem by my 4A colleagues who believe that his artistic contributions have played an important role in the development of contemporary Asian art in Australia. It was with this history and context in mind that I felt slightly overwhelmed and unequipped—and not least awe-struck—when I was appointed as curatorial assistant for An Omen Near and Far. As an emerging curator and arts administrator I had never entertained the idea that my first collaborative exhibition experience would be working alongside such a prominent artist.

Upon being appointed to this role, I nervously awaited my first meeting with Dacchi. Looking back, these nerves were in part a reflection of my self-interest concerning how I would perform in my first curatorial role. However, in addition to this, it had been reiterated to me how long overdue and important Dacchi’s survey show was, not least for the institutional role survey shows play in contextualising and repositioning an artist’s oeuvre, but also because this was such a momentous moment for Dacchi himself; indeed, later he would remark during the exhibition’s opening, ‘This is the first time in my career that some of these works have ever met.’ This was Dacchi’s moment, in which the progression and maturation of his artistic practice was laid bare for public presentation. I’m sure there was a sense of fulfilment and gentle pride in seeing his life’s work presented in its entirety.

At my first meeting with Dacchi as part of the curatorial team we sat in 4A’s office sharing a pot of Chinese tea, fleshing out the breadth of his career, making rough sketches of potential exhibition layouts and planned studio visits. Dacchi is an immensely kind-hearted and warm individual; he was incredibly modest about his skills and achievements, speaking with insight and enthusiasm about the techniques, materials and equipment he uses during the creative process to produce his works. Dacchi’s appreciation of the material processes of art-making shed light on his mastery of the photographic craft, and the pleasure he finds in working with analogue techniques.

Dacchi Dang documenting the construction of The Boat, 2001; Gallery 4A, 26 October – 17 November 2001, courtesy the artist’s archive

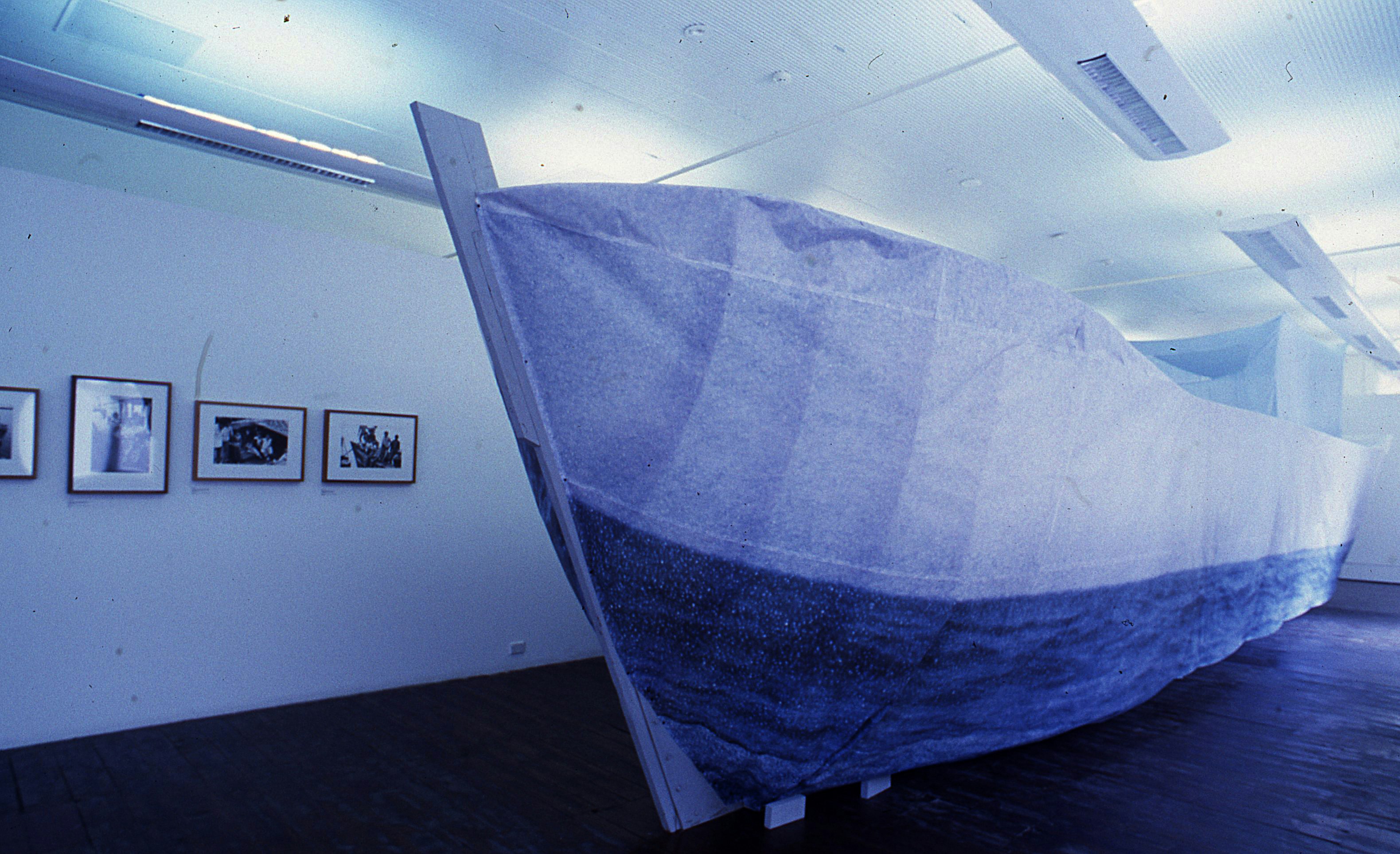

Dacchi Dang, The Boat (installation view), 2001; photo: Dacchi Dang, courtesy 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive.

Before I began work on An Omen Near and Far, I was unaware of the extent of Dacchi’s artistic practice; his iconic installation, The Boat (2001), in which he reconstructed a life-size Vietnamese fishing boat similar to the one he fled Vietnam in, at that time exclusively underwrote my understanding of his practice. There is of course so much more to Dacchi’s practice than merely visual expressions of his experience as a refugee. While The Boat was an ambitious project, his photographic series are more modest and nuanced in their execution, but not to be mistaken as less affecting. The breadth and visual complexity of Dacchi’s experimentation with alternative photography—portraits incised on gold metal plates, lively photomontages, cyanotypes of the Australian landscape rendered in brushstroke suggestive of Chinese calligraphy, pinhole photograps capturing haunting imprecisions of reality, and bamboo forms cast in wax and inlayed with photographs—conveys a practice that is both multilayered and experimental, allowing one to look past Dacchi’s refugee experience and instead look to the complexities and breadth of the multifaceted ideas explored in his oeuvre. Yet before one can do this, one has to first confront this history, which is why I commenced my research by reading Dacchi’s 2012 PhD thesis, The Artist as Explorer: How Artists from the Vietnamese Diaspora Explore Notions of Home, the first chapter of which details his personal experience as a refugee (1). While Dacchi emphasised that he did not want his career to be reduced to a refugee story, it was important for me to understand the trauma and risk of his exile, and how it has played a crucial part in determining his character formation and life choices. His art is deeply informed by this trauma, many of his photographic series are underscored by an investigation of loss, an ongoing search for belonging and contested forms of cultural memory, both on his own behalf, and sometimes on the behalf of others.

This kind of contextualisation led me to research the social and political climate in Australia from the mid-1980s up until the early 2000s, a period that fundamentally shaped modern Australia well before I reached adulthood, then too young to be interested in politics and which was subsequently not touched upon in my formal education. While Dacchi’s refugee status gained him a degree of cultural acceptance, an excess of ideologies of majoritarianism and racialised nationalism from political influencers such as Pauline Hanson and John Howard formed resistance to the premise of such acceptance, and often hostility towards ‘boat people’ and ‘Asians’ in general. During this time, Dacchi produced some of his most seminal works, which allowed me to understand how his art was not speaking of but out of these particular times and experiences.

Both my personal friendship with Dacchi and my professional experience gaining insight into the evolution of his practice prompted me to write my dissertation on his art for the culmination of my Master of Art Curating degree at the University of Sydney (from which this essay has been adapted in part). I had never considered myself an overly political person, and by that I mean no matter how dissatisfied I am with the state of public affairs I’ve never felt motivated to participate or take explicit action. Dacchi’s art pricked my interest in politics and really brought into focus the growing alarm in Australia about the arrival of refugees and asylum-seekers on Australian shores and the strident demands for intensified border control. My dissertation reflected a debt I felt I owed to Dacchi, not just because it gave me a sense of the complexities surrounding issues on refugees, but because it was the first time during my art careers infancy I had truly felt the affecting impact of art, even through the otherwise ‘mute’ nature of photography.

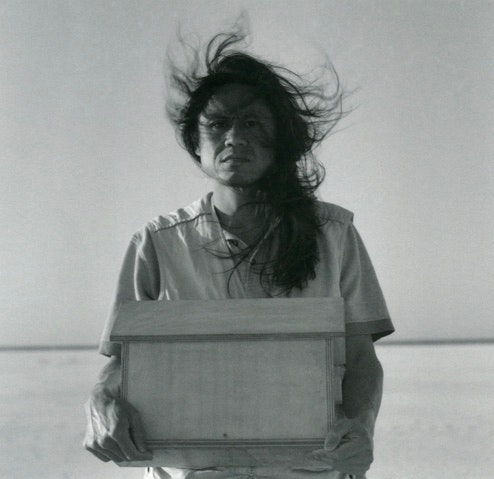

Dacchi Dang, Self-portrait I from the series Full Circle, 2009, pigment on photo rag; courtesy the artist.

Dacchi Dang’s work is fundamentally ground in the analogue photographic image despite manifesting across multiple mediums. He employs complex aesthetic strategies that privilege beauty, expression, feeling and judgement that attenuate darker shadows on the social conscience of nations. An example of this can be seen in his Self-portrait I (2009) from the series Full Circle. This portrait was created whilst Dacchi was an artist in residence with Metro Arts in Brisbane. The portrait was captured on Peel Island (Teerk Roo Ra), located east of Brisbane in Moreton Bay, which is one of Australia’s most concentrated sites of Indigenous dispossession by colonial invasion, and also served as a quarantine station and asylum for leper sufferers who were exiled to the island to live out their days. While the island has layers of historical complexity, the landscape in Dacchi’s portrait is nondescript, yet generates a richness of metaphorical play. The self-portraits from this series emanate an otherworldly atmosphere—a desolate landscape defined by a distant, hazy shoreline; the artist’s unruly hair at the whim of powerful, unpredictable forces. Yet this is offset by the intensity of the artist’s gaze and his firm grip on the handmade pinhole camera, a gesture that signals a desire to record his presence in an environment that reminded him of ‘being held in a state of near powerlessness on the margins of civil society’, while he resided intermittently in a refugee camp on Pulau Bidong off the east coast of Malaysia (2).

When Dacchi first visited Peel Island he knew very little about its history, an intentional decision on his behalf, as he wanted to be guided by his visual instincts and spontaneity. After spending some time on the island, Dacchi felt that the landscape—particularly through the derelict structures—conjured memories and feelings of his own experience of isolation, dislocation and marginalisation on Pulau Bidong. He believed these feelings, at least partially, would have been similar to the experiences shared by the people exiled to and from Peel Island, who were disconnected from their family, friends and former lives. Dacchi’s aim became not just an investigation of the island’s history, but also an exploration of self through personal memory. By drawing on his own memories as a refugee and local sites of often hidden histories to inform the ambivalent quality of this self-portrait, the artist reveals how belonging, national identity and citizenship do not always operate as the logic of segregation and discriminatory injustice. Instead, this self-portrait embodies an idea that individuals are often controlled physically and geographically, strictly regulated in arbitrary ways that are politically instrumental to maintaining exclusive national communities and identities.

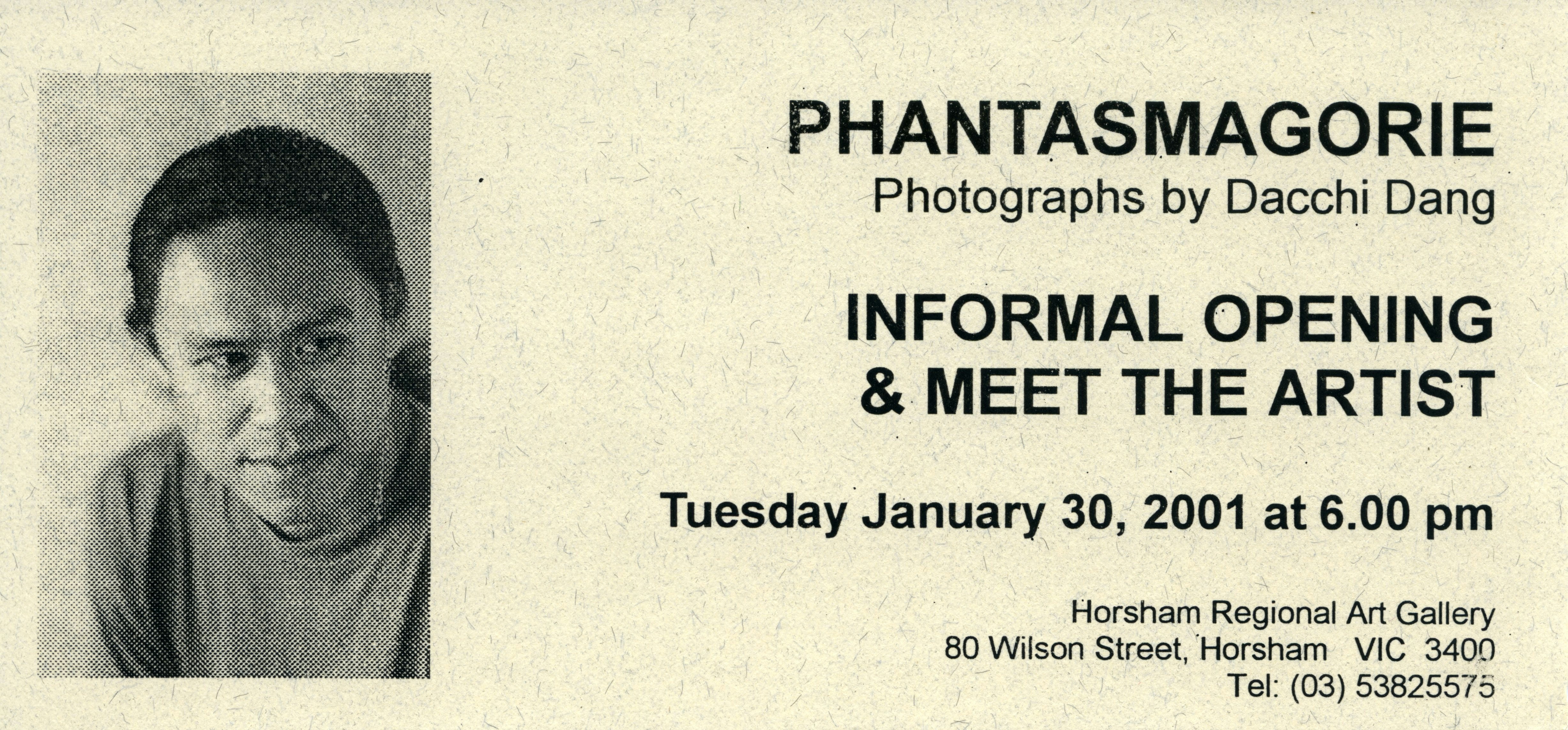

Exhibition invitation; courtesy the artist's archive.

In early 2016 I was entrusted with overseeing the digitisation of 4A’s archive, the content of which is a uniquely tangible record of the trajectory of Asian-Australian art in Australia since 1996. When I started this project, the archive was full of textual detritus ranging from old facsimiles whose carbon messages had completely faded to receipts for everyday items, but also invaluable exhibition catalogues, room sheets, correspondence and photographic transparencies. The archive was not even remotely organised in chronological order, nor was it limited to one dusty storeroom, but was hidden in overflowing boxes scattered throughout the gallery’s de-facto storage spaces: behind temporary walls, on windowsills, in drawers. Every week, a new year from 4A’s two-decade history was unearthed as I worked my way through this strata. The sorting of 4A’s archive highlighted the importance of realising the organisation’s identity; the development of the gallery interpreted through reference to past occurrences in undiscovered textual territory, tracing particularities of our character from past events.

There is an assumption that archives are an attractive place to pursue research because of its symbolic value as a repository of truth and authenticity. Just at the perfect time, I stumbled across a selection of textual and pictorial material from the archives relating to Dacchi: exhibition ephemera and documentation, reviews, interviews and critical texts published over the course of the artist’s career. This discovery lead to my first task as curatorial assistant, being charged with developing a documentation ‘hub’ to be presented as part of the exhibition that would help audiences contextualise Dacchi’s practice within broader social events. Dacchi also provided his own archival material—photographic proof sheets, newspaper clippings, exhibition catalogues—which he has meticulously collected throughout his career. The documentation hub came together through a process of sorting, scanning and photo editing, and was displayed in a very pragmatic way: a folder of black-and-white photographic contact sheets and an iPad time capsule of other material. The process of curating this material was an education for me; for instance, as a so-called digital native I had no idea what a gelatin silver contact sheet looked like (much to others’ amusement!) and I had also never worked with original transparencies before. Having experienced the switch from analogue to digital—pre- and post-internet paradigms—in my lifetime, the graininess, fuzziness and overall tone and texture in Dacchi’s black and white photographs heightened my own sense of nostalgia; I was taken back to the grainy films of my childhood, underscoring the particular quality of analogue photography (as Barthes, Sontag and others have always reminded us) that tethers time to a fixed referent of embodied reality.

Dacchi Dang, Et in Arcadia Ego (detail) with the artist in the background, Dacchi Dang: An Omen Near and Far exhibition opening performance, 8 June 2017; commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, photo: Document Photography, courtesy the artist.

Dacchi Dang, Untitled (photographic documentation), 1994, reprinted 2017, original installation: photographic emulsion on wax candle panels, charcoal drawing, black and white gelatine silver prints, from the exhibition Upstairs/downstairs, National Art School, Sydney, 1994; 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, An Omen Near and Far, 2017, photo: Document Photography, courtesy the artist and 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art.

Dacchi Dang’s work explores sensitive and at times contentious subject matter through subtle, non-sensationalised and restrained aesthetic techniques which achieve a pictorial modesty. It was important for An Omen Near and Far to work as an exhibition that we captured the breadth and depth of Dacchi’s practice. A way of bringing the past into the present was achieved with the inclusion of a new work, Et in Arcadia Ego (2017), that was commissioned by 4A especially for the exhibition. Taking over the ground floor gallery was a forest-like installation of bamboo forms cast in wax and inlayed with torn strips of photographs. The photographs revealed scenes of Saigon in 1994 (Dacchi’s first return to Vietnam following his emigration to Australia in 1982), and Hanoi in 2017 (his second trip and, significantly, his first visit to the capital) (3). Et in Arcadia Ego was designed to burn over the duration of the exhibition as a series of performances, and was a reprise of one of Dacchi’s earliest works Upstairs/Downstairs (1994), an ephemeral installation staged at Sydney’s National Art School. This latter work, in which he burnt three sculptural wax panels embedded with imagery of street scenes of Saigon and the Mekong Delta’s Bến Tre province, represents a seminal work in the development of Dacchi’s artistic vision. Seen alongside each other, these works are separated by time yet conjoined conceptually. Curatorially, we decided to present reprinted photo documentation of Upstairs/Downstairs alongside the new wax installation, a simple curatorial strategy that emphasised how Dacchi has reflected, reconfigured and rejected ideas over time.

Concurrent to 4A’s survey exhibition, Dacchi completed a body of work for the Australian War Memorial, in which he was commissioned to create works using the Memorial’s collection to address the gap in Vietnamese-Australian perspectives on the Vietnam War as presented through the national institution’s art collection. This opportunity arose following a bequest by the retired Major John Milton Gillespie, a Vietnam veteran and immigration consultant, that was left to the Memorial to acquire works of art. The first result of this two-stage commission was a work titled Brothers in Arms, comprising five rectangular plywood panels depicting montaged scenes of Vietnamese and Australian soldiers training together, and finished with a dark red overlay of lacquer. The art of Vietnamese lacquer painting, the medium most associated as ‘traditional’ in Vietnam, further shows the diversity of Dacchi’s talent and expressive mediums. The selection of Dacchi, and the contribution of his work to the Memorial is particularly pertinent given his reputation as a preeminent Vietnamese-Australian artist who has had a practice that has spanned nearly thirty years.

Dacchi Dang undertaking research at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, December 2016; photo: Daniel Spellman, order reference: AWM2016.8.229.12, courtesy the Australian War Memorial.

As previously noted, I recently completed a Master of Art Curating at the University of Sydney. Degrees of this kind are necessary foundations that help attune theoretical knowledge about art history and current contemporary art trends with the more practical aspects of exhibition making. However, there is a huge disjunction between what is being taught at university level and the reality of the curator’s job. In reality, an exhibition takes shape largely through administration and correspondence. While this can be dry work at times, I understand it is of course an essential part of the ‘coordinating’ and ‘organising’ that brings the exhibition off paper and to life. The words coordinating and organising are not often used to describe curating (with the exception being North America where exhibitions are commonly ‘organized’ by … ), but in my opinion are the two words that best capture the role of a curator. The practical component of curating, which most people would view as the creative side of curating, occurs largely during the weeks of installation. This was one of the more challenging aspects during my time as curatorial assistant, as the practical skills you develop are largely intuitive but simultaneously are mastered only through years spent in the industry collaborating with fellow curators and artists, and knowing your locale Bunnings Warehouse intimately.

Dacchi Dang has made an indelible mark upon the world through a steadily consistent art career that has never seen him waver from rigorously investigating Vietnamese disaporic experiences, dislocation and notions of home and belonging. An Omen Near and Far was a genuine attempt to critically appraise Dacchi’s career, reasserting its continuing relevance in both art historical terms and within the broader cultural sphere. History weighed heavily in this survey but not in the usual formulaic ways, rather through the inclusion of an array of works that differ stylistically, across time, genre and scale. This revealed a remarkable and rare time capsule of imagery that is at times deeply personal and at others a more historical consideration of nations in states of flux and visual representations and responses to shameful blots on the social consciousness of nations.

Throughout the exhibition’s duration, Dacchi and I sat together in the downstairs gallery, watching his bamboo forest steadily temper and form wax stalactites. We would talk about any number of things, but mostly I would ask him how he realises an artwork, where he begins and when he knows to stop? Dacchi told me about his ongoing experimentation with different mediums and processes, and all the successes, failures and temporary periods of ‘not much happening’ in the way of creating. In this vein, it reminded me that curating has its busy periods and its lulls, but it can also be hard to feel inspired or determine exactly what an exhibition needs to be properly experienced by audiences. These discussions made us both realise that lively conversations, bouncing ideas off one another, can not only be incredibly informative but are in fact crucial to understanding that empathy is an avenue through which ideas can be more fully apprehended.

About the contributor

Harriet Reid was curatorial assistant for the survey exhibition Dacchi Dang: An Omen Near and Far at 4A.