Dig down desire

Lauren Carroll Harris

Geumhyung Jeong, Oil Pressure Vibrator, 2016; photo: Karolina Miernik, courtesy the artist and Performance Space.

Here’s the truth: sex is funny. It’s absurd and complicated and great and weird, and that’s what makes it funny. Why is that so rarely acknowledged?

Another truth: even in a sex-obsessed raunch culture, we only speak about a fairly narrow spectrum of sexuality. Beyond a fragment of common kinks and desires lies a whole other universe of inclinations and barely-withheld repressions.

South Korean artist Geumhyung Jeong’s recent one-hour performance lecture Oil Pressure Vibrator, an Australian premiere as part of Performance Space’s Liveworks festival, illuminated both these ideas. The work traced a personal narrative in which the artist stops sleeping with men and embraces a version of what she calls hermaphrodity: an autoerotic state where she splits her identity in two and sleeps only with her own imaginary lover, conceptualised as a ‘he.’ In dividing herself she becomes a truly independent being, akin to a invertebrate that spontaneously regenerates and holds the properties of two sexes within the one body. (Another rarely mentioned truth: there are more than two sexes.)

Geumhyung Jeong, Oil Pressure Vibrator, 2016; photo: Gajin Kim, courtesy the artist and Performance Space.

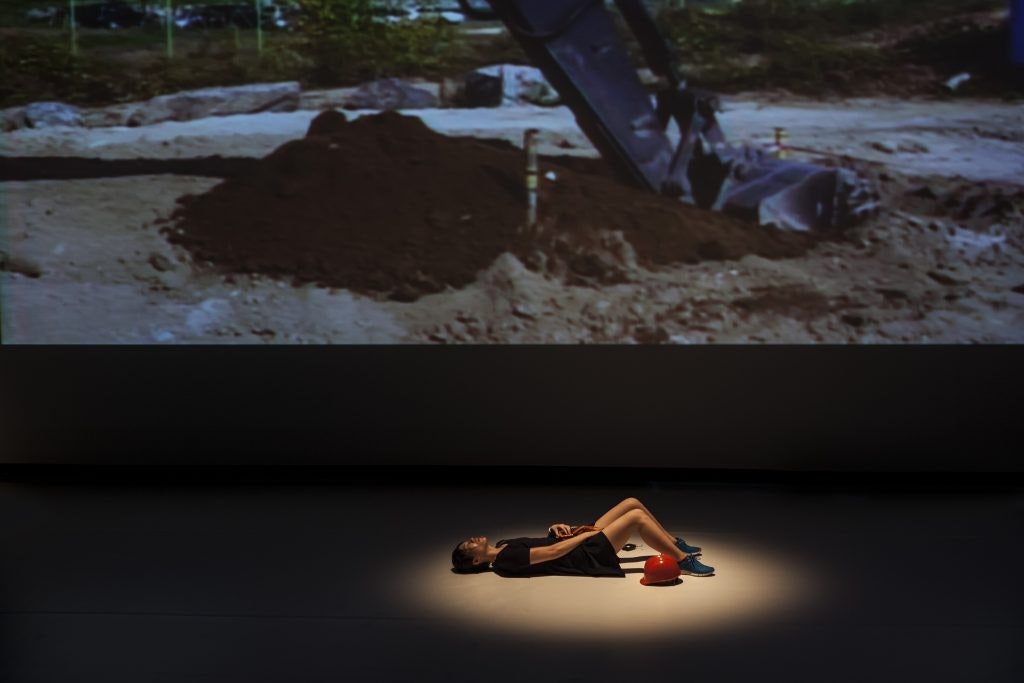

Jeong’s path deviates again when she renounces the idea of human lovers altogether after spotting a red, spindly industrial excavator in a street-side construction site. A lo-fi video registers her astonishment. It is lust at first sight, but the course to fulfilment is treacherous, involving earthmover driver training and a high intensity exam to grant her a license. The expression of her newfound sexuality demands a whole new skillset for the choreographer, dancer and performance artist, but she is up to the task. She narrates her journey from the side of the stage in unsmiling deadpan and impassive language that occasionally dips into the detached vocabulary of psychology—it’s a strange comedy. An orange hardhat covers a spot-lit model excavator that is placed centre stage in front of the video projection screen, and at other times she performs, on video, a kind of sexy duet with a stretchy vacuum cleaner pipe.

Within all of this lies a deep spiritual and sexual synergy with machines. This synergy already happens elsewhere, maybe everywhere: in the vibrators we load with AA batteries, in the cold-glowing laptop screens that deliver our porn. But Jeong is talking about something else: an industrial sexuality that manifests deliberately around machinery. Crucial to the performance is that it is delivered in Korean language and subtitled onscreen, bringing a layer of abstraction to the highly verbal lecture format and positioning the Sydney audience as outsiders looking into a faraway world: you don’t have to read this literally.

Somehow, over the course of an hour, Jeong makes her industrial excavators appear alive, affectionate, thirsty, mobile: she performs objects in a series of passionate encounters, imbuing them with human qualities. These objects are drawn from her personal collection, a sliver of which is currently exhibited under fluorescent light at London’s Delfina Foundation: mannequin heads, detached plastic bodies, industrial vacuum cleaners, rows of their slinky hoses, tiny robotic Hoovers, and medical apparatuses alongside blow-up dolls. The exhibition is hyper-aware of the ways in which context shapes how we think of objects: by transporting these mainly plastic artefacts into an art space, with all the museological conventions that go with that, Jeong transforms them into sculptural forms, immediately making us think of them in a sexual light. Anything can be animated with erotic potential. Objects have their own lives, their own trajectories toward and away from us; how easy it is for them to become coupled with sex.

In her performances, snippets of which were both enacted live and presented in video in Oil Pressure Vibrator, Jeong animates her objects (or do they possess and animate her?) by putting them in unexpected places. Clothed in black, she balances an impaled white mask on her foot and snakes across the ground, like the giant, airy beings in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. In the presentation’s opening video, Jeong is wrapped in azure fabric and surrounded by a further sea of it, folds rising up in small waves. A model boat is sewn into the fabric along the length of her abdomen, and as she arches her spine, it undulates in its blue synthetic ocean. Geong is a puppet, and she is the puppeteer.

I am told that the artist doesn’t do interviews for the rational fear that mainstream journalists will read the material literally, individualising and pathologising the artist and her subject matter. She’s probably right to withhold herself—the work is too weird, too associative for most of the press. Oil Pressure Vibrator speaks to much murkier, deeper issues than its openly masturbatory content: why we arbitrarily deem some objects sexually acceptable and not others, the way human desire is already bound up with the technology of the day, why love and desire don’t always mix, how longing unleashes itself from humans in all sorts of unpredictable ways.

I am told that the artist doesn’t do interviews for the rational fear that mainstream journalists will read the material literally, individualising and pathologising the artist and her subject matter. She’s probably right to withhold herself—the work is too weird, too associative for most of the press.

There are many others who have relinquished people from their relationships. An online documentary, Married to the Eiffel Tower, follows women who have variously been in love with the Berlin Wall, the deceased Twin Towers, a bow and arrow, a fairground ride and a humble staircase banister. From offscreen, the documentary-maker asks why anyone would ‘prefer the coldness of concrete to the warmth of a human body,’ forgetting that the world is already a place where individuals feel isolated, where other people can be inhospitable and disappointing and objects endearing and lasting. ‘Our love is no different than the love of any other two beings,’ says a woman whose true love is the Golden Gate Bridge, later confessing, ‘One of the difficulties of being in love with a public object is that he and I can never be truly intimate.’ She makes do with a miniature model. However, other possibilities arise for literal lovers of grand architecture. One YouTube commenter writes: ‘Going to the city for them is like going to the strip club.’

The documentary terms its subjects ‘objectum sexuals: people who have loving relationships with objects.’ I don’t sense that Jeong is moving toward this kind of bracketing however. Her show, and the practice from which it springs, speaks more to fluidity than categorisation, to a broader questioning of what binds together humans and technology in the present moment, to the idea that sexuality isn’t just about the gender/s to which you are attracted, but to what you like to do and what you like to experience during sex: to who you are sexually. Our ideas about sex and gender are shaped by forces beyond us, beginning from early childhood, with the dominant messages received from parents and family about how to exist in your body, about boys and girls and men and women, about naturalness and shame and awkwardness and guilt and abuse and control and care, and these ideas keep moving as we age. Though it is common, now, to talk of sexuality as a spectrum, Oil Pressure Vibrator subtly suggested that an individual’s position on that spectrum can slide about, that sexuality changes as your life does.

Jeong’s work wrapped itself around me in strange ways, kept me thinking, as I think all good art does. It ended with a moving image of destruction: a video of an excavator on a lonely beach. A giant sandcastle woman lies in the sand (much like the one in The Master that Joaquin Phoenix, as an intimacy-starved marine, carefully moulds, lies next to, and pretends to have sex with) as the giant excavator approaches from across the wide bay. By slowing down the length of the video’s shots, Jeong induces real tension. In front of the screen, she lies with her legs apart and the model machine on her stomach. Finally the giant excavator reaches the sandcastle woman, and we cut to a shot that excludes the figure entirely, focusing on the tip of the machine’s arm. Annihilation is the mandate: finally it levels her and she returns to an unformed state at the edge of the waves. After all, what is an orgasm but a little death, a loss of cognisance, a submission to the subconscious, on an ever-longer spectrum.

About the contributor

Dr Lauren Carroll Harris is a writer, researcher and artist.