Indigenous artist-curator relationships in the militourist present

Dr Léuli Eshrāghi

The following text is an abridged version of a presentation given by Dr Léuli Eshrāghi at the Wansolwara Symposium, held 18 January 2020 at UNSW Galleries, Sydney.

I lēnei itulā, avea ia loʻu leo e fai ma fofoga taumolimoli i le Iunivesitē o Ausetālia i sasaʻe, e faʻatālofa atu ma faʻafeiloaʻi atu le paʻia ma le mamalu le asō. Tātou mālō faʻaaloalogia ae maise le paʻia ma le mamalu o lēnei taeao. Mālō le soifua, mālō le soifua manuia. (1)

To the Bidjigal and Gadigal peoples, I am a grateful visitor, treading with humility and respect in your territories, bringing my Sāmoan, Persian, Cantonese and European ancestors’ teachings of good conduct and peace with me.

Nullabor No trees

Terra nullius Land empty of people

Mare nullius Sea empty of people

West and its supposed Enlightenment \\ E M P T Y

Incapable of recognising spatial relationships between all things

Incapable of surmounting the craze for empire (2)

In my language Gagana Sāmoa, Vasalaolao (Great Ocean) signifies the great undulating sacred relational space, a third of this planet. In my friend Gunantuna (Tolai) artist and curator Lisa Hilli’s language Tinata Tuna, na Ta signifies the deep ocean, the far-reaching body of water often mistakenly called Pacific by newcomers and old timers alike, such is the impact of colonial intellectual and geo-cultural impositions.

Like our relational ways of belonging to the fluid expanses, languages and cultures colonised and undergoing revival, the Great Ocean’s Indigenous knowledges and peoples will outlive colonial capitalism’s climate apocalypse. Nothing to do with European seafarers who heralded the times of disease, enslavement, germ warfare, nuclear testing, fossil fuel mining and unending massacre: Magalhães [Magellan], Cook, Bougainville, Flinders, Dumont D’Urville, Tasman, Vancouver, da Gama. Instead, master navigators maintained continuous trade, ceremonial–political exchange, and voyaging routes between every shore and coast of a third of this planet’s surface for thousands of years, until the interruptions mentioned above and the borders implemented by colonial design on maps of settler and military imaginations in Europe, North America and East Asia.

Reading room, The Commute, the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; image courtesy of the Institute of Modern Art.

The present and future of Indigenous time–space in our region is not defined by cis Caucasian men, nor their ways of thinking and being in the world, originating from a small far-flung region called Europe. Our worlds are realised by us multigendered, sensual, spiritual beings committed to renaissance, balance and undoing all the traumas—for us to live and love in heterogeneous Indigenous brilliance and complexity, in relationships with habitats and sky/water/land creatures who must have futures for us to also have futures.

Remember:

lutruwita, Mer, Redfern, Palm, Bikini, Enewetak, Maralinga, Emu Field, Monte Bello, Moruroa, Fangataufa, Manus, Amchitka, Malden, Christmas, Johnston, Kaho‘olawe, O‘ahu, Guåhan, Kanaky, Okinawa, Fukushima, West Papua

Exploded ordnance is/lands l/agoons at/olls

Unconscious warmongering as homelands

Nuclear catastrophe as belonging

Poisoned well as body

Cauterised organisms as spirit (3)

Visiting curators skype, clockwise from top left: Lana Lopesi, Freja Carmichael, Dr Léuli Eshrāghi, Tarah Hogue, Sarah Biscarra Dilley; image courtesy Dr Léuli Eshrāghi.

My practice is anchored in considering Indigenous ways of being, organising, loving, world-making and caring that pre-date and will post-date Euro-American norms and knowledges. Where can our sensual and spoken languages take us? Which movements are necessary and more than just salvatory in the militourist and indebted present? With multi-generational diasporas across large geographies, what constitutes pre-colonial Indigenous governance and alliance-making and how can this be rendered differently now into our futures? How can we restore ceremonial–political structures currently dormant or hidden from us?

The web of slave trading, of commerce in sandalwood, kauri pine, sugarcane, coffee, vanilla, copra, pearls, sea cucumbers, spices and minerals, of networks of profiteering from mass incarceration continue to unfurl in their complexity and disregard for human and kin suffering, broken ancestral connections, race hierarchy based torture and the debasement of people seeking reprieve and new beginnings from trauma and violence. Colonial entitlement and fragility continue to negatively impact Indigenous renaissance within and outside territories and bodies. These situations across the Great Ocean severely impute the capacity for Indigenous languages to be practiced and enriched, for translation to be possible across ethical constructs, to be valued and empowered in their homelands and in the displaced and diasporic bodies we move within. Speaking in English right now is a form of violence to this Bidjigal and Gadigal Country that is both epistemic and spiritual, whereby the possibility of connecting and respecting this sacred territory on its own terms through the knowledges of local First Nations, through humility-based deep listening, is excluded by Western structures of linearity, discourse and control.

In I-Banaba, I-Tungaru and African-American theorist and scholar Teresia Teaiwa’s seminal essay critically analysing celebrated French pedophile artist Paul Gauguin’s writing and paintings, the satirical decolonial writing of visionary iTaukei Viti and that of Tongan writer and scholar Epeli Hauʻofa, Teaiwa defines the militourist industrial complex in multiple contexts across the region, particularly in Hawaiʻi, Tahiti, Guåhan [Guam], Ryukyu [Okinawa], Kanaky [New Caledonia]—and I would include the Northern Territory and Taiwan—as being rooted in Fernão de Magalhães’ [Ferdinand Magellan’s] 1521 encounters with Chamorro in Guåhan and as expanded by various empires emboldened by settler colonial entitlement: ‘Militourism is a phenomenon by which military or paramilitary force ensures the smooth running of a tourist industry, and that same tourist industry masks the military force behind it.’ (4)

Skype call between Lisa Hilli and Dr Léuli Eshrāghi; image courtesy Dr Léuli Eshrāghi.

Ongoing relationships in chosen and bloodline kinship are a widely practiced Indigenous way of being. For the recent project The Commute, held from 22 September to 22 December 2018 at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, myself and four other Indigenous curators—Freja Carmichael, Lana Lopesi, Sarah Biscarra Dilley and Tarah Hogue—worked for over one and a half years to create an artist-centred project that then grew to span two years and other distinct iterations. One of our primary achievements was securing multiple public funders for an unprecedented investment in eight artists’ practices. We wanted to see our local and international Indigenous peers enjoying much improved conditions for the production, exhibition, scholarship and dissemination of contemporary art practice. The five of us termed ourselves ‘visiting curators’, to continue thinking through what being a good Indigenous kin visitor is and can be, how we are able to grow in our new working and personal relationships with each other and with artists from communities where we already have strong kinships. We met at Aboriginal Curatorial Collective/Collectif des commissaires autochtones gatherings in Whitehorse, Northern Canada, at friends’ barbecues in Brisbane, and at Indigenous art residencies in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Banff, Canada.

Lisa Hilli, Sisterhood Lifeline installation view 2018, The Commute, the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; image courtesy of the Institute of Modern Art.

Gunantuna artist Lisa Hilli and I regularly met to swap words of Tinata Tuna and Gagana Sāmoa that we’d learnt, and the Tok Pisin and English that we already spoke fluently, and to exchange ideas and understandings, particularly as we were both graduate students at the time. I accompanied the development, production and exhibition of her major work Sisterhood Lifeline (2018), engaging with the impacts Eurocentric cultural institutions—public, non-profit, private galleries, libraries, archives and museums—have on Bla(c)k and Brown Indigenous women and non-binary folks in Australia, and the kinship-based extramural support network that sustains them throughout.

We co-authored a multilingual ‘Tolaisphere’ where Lisa and my worlds and ancestries could meet for visitors and Gunantuna communities alike, inspired in part by writing by Zoe Todd and Édouard Glissant, and by all the times we wanted to find glossaries not written by colonisers. Creating the Tolaisphere meant defining a space and the then-present moment in time for Lisa to express how she lives and considers her Gunantuna (Tolai) belonging, outside her homeland, with distinct genealogy and lived experience. This was a textual space where Lisa’s own fingerprint within the collective whole could be held and kept, where Gunantuna (Tolai) knowledge, history and kinship were centred, unlike the overwhelming majority of ‘authoritative’ academic, religious and administrative texts written about Gunantuna people and territory by outsiders. Lisa and I navigated shared German colonial archives and the dispossession or displacement of situated knowledges, ceremonial–political practices and ancestral belongings by that administration, the churches, and the Australian colonisers who followed.

Lisa Hilli and Dr Léuli Eshrāghi speak in front of Sisterhood Lifeline, within The Commute at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; image courtesy the Institute of Modern Art.

The first of three major projects, The Commute in Brisbane at IMA in 2018 was followed by Layover (15 March to 25 May 2019) at Artspace Aotearoa in Tāmaki-makau-rau Auckland, and Transits and Returns (28 September 2019 to 23 February 2020) at Vancouver Art Gallery. We sought to centre the artist–curator relationship and re-balance the ways we work in the art sector. We continued our significant prioritisation of artist fees for production, travel with family, research travel and exhibition rights at Artspace Aotearoa, and in Vancouver while we worked within the beast of a much larger, more conventional art museum with more severe budget constraints, most of the artists, curators and contributing writers to the catalogue were still able to attend the opening gathering in late September 2019 and be paid decent fees.

We shielded the artists from most of the institutional bureaucracy and ensured payments were honoured on schedule, that contracts abided by Indigenous cultural and intellectual property principles, and worked hard to secure funding from public agencies in multiple countries so that we were able to provide minimum artist fees for the first two projects in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand of A$3000, production fees of A$2000–5000, and travel support of A$2000–4000; well in excess of what major institutions in both these countries provide for group exhibitions.

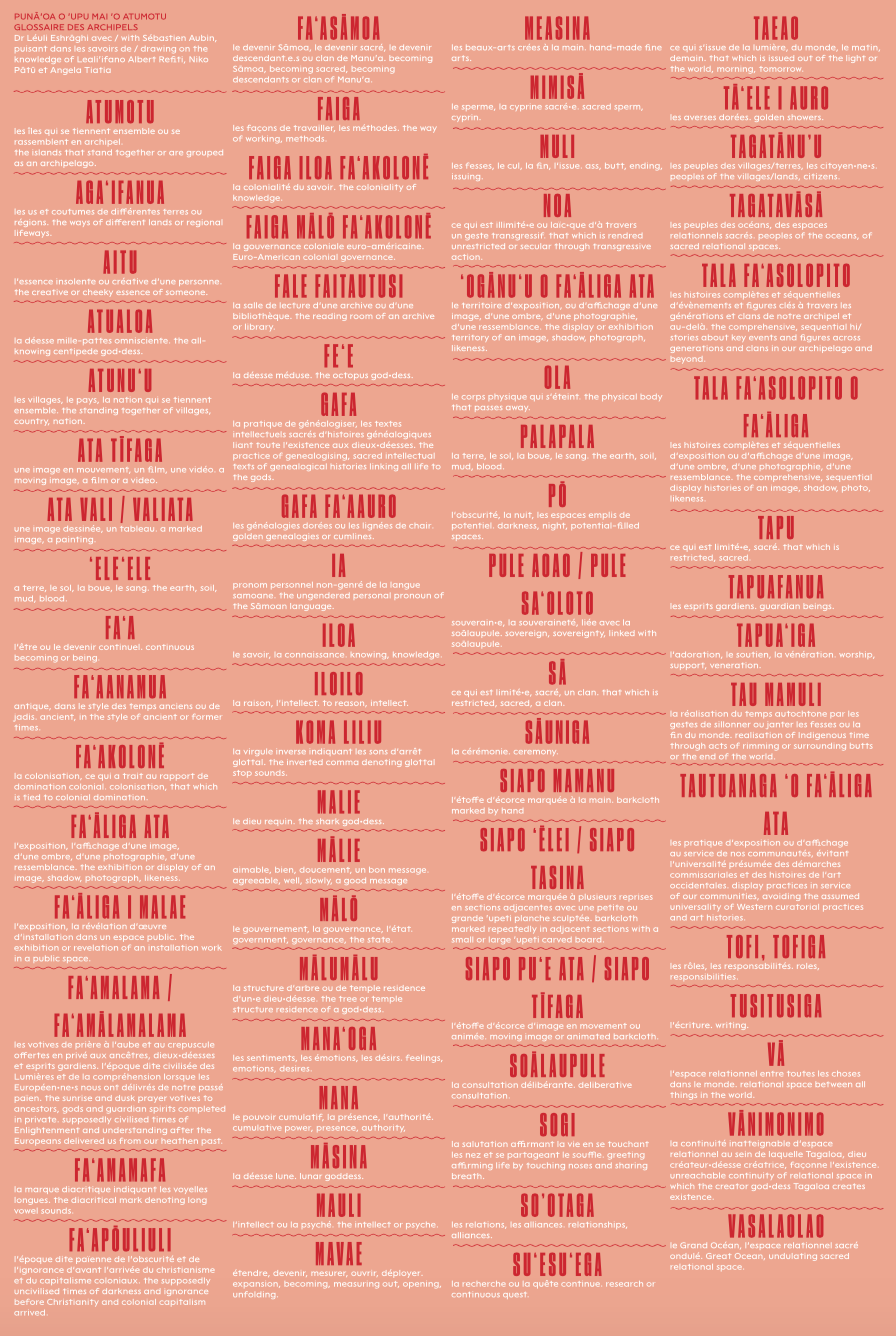

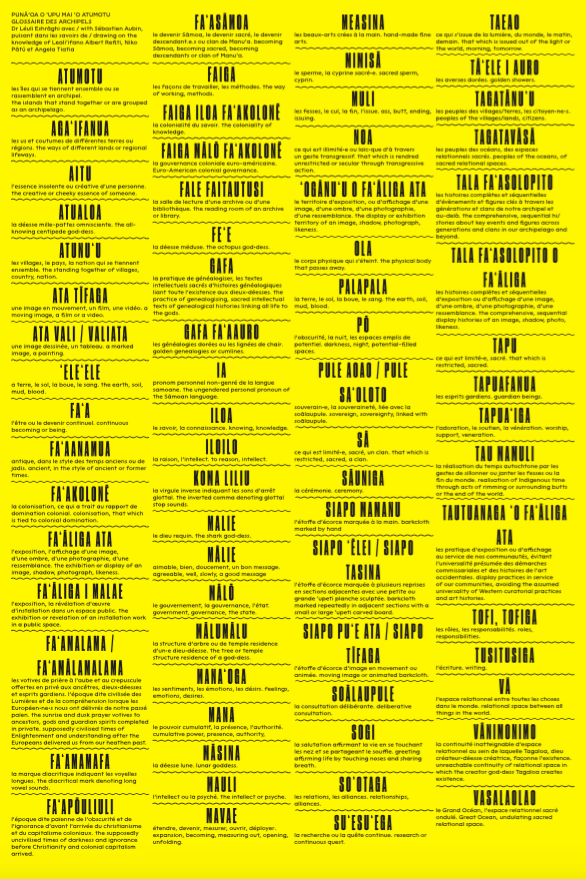

In 2019 I composed a poster-form multilingual guide in Sāmoan, French and English called Punāʻoa o ʻupu mai ʻo atumotu/Glossaire des archipels to represent currents of thought and action in international Indigenous visual cultures. Drawing on extensive learning and mentorship with peers around the world during and since my doctoral research into Indigenous curatorial practice, this artwork was fashioned in collaboration with celebrated Nēhiyāw graphic designer and typographer Sébastien Aubin.

I want to offer three terms framed in this work that are particularly relevant when thinking through negotiations of the settler colonial structures of learning, creativity and dissemination in a university art school context: first, Faiga iloa faʻakolonē, denoting the coloniality of knowledge as epistemologically derived from empire-driven Western European states and their breakaway colonies around the world; second, Tala faʻasolopito o faʻāliga, specifically pertaining to the comprehensive, sequential display histories of images, shadows, photographs, likenesses, as opposed to enduring, circular genealogical time-derived histories; and third, Tautuanaga ʻo fa‘āliga ata, meaning a display of images, likenesses, photographs or shadows that serves collective well-being. Considering these three concepts within the present context of increased priority to Indigenous cultural values and histories, faiga iloa faʻakolonē, tala faʻasolopito o faʻāliga and tautuanaga ʻo faʻāliga ata enable understandings of all texts imprinted on bodies, lands, waters, digital files and other formats as the latest manifestation of genealogical matter and imperatives that direct our actions into the times yet to come.

Today I want for new Indigenous histories of the Great Ocean

No longer flat, never pacified

Born in the darkness before the all-encompassing History of an Enlightenment already extinguished

Of European homelands, their settler and militourist colonies, searching for balance and cleansing of their widened gaps and racialised, heteroformal excesses

Today I want for us to remember the pō of the beginning of the universe, full of connection and possibility (5)

Freja Carmichael speaks at The Commute, The Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; image courtesy Institute of Modern Art.

Building our own spaces completely independently of existing spaces, while emancipatory, does not address colonial practices that control discursive authenticity, grand narratives and, most importantly, financial, human and physical resources. Later in 2020 I will be releasing a new series of poster artworks in collaboration with Sébastien Aubin, this time a mapping of Indigenous art representation in university programs in studio arts, art history, and curatorial and museum studies in Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, Viti, Hawai‘i, Canada and the United States; and of Indigenous art representation in public, non-profit and private art galleries, museums and libraries in these same contexts. Of course, an Indigenous presence in these cultural institutions—learning, making, exhibiting, disseminating, and researching—is conducted under colonial duress and pressure. These conditions pertain to the lack or development of cultural competency, non-tokenised ongoing Indigenous personnel in specialist roles with financial and programming autonomy and, particularly in years to come, mainstream positions filled by Indigenous staff in generalist roles.

Is it so hard to imagine numerous Indigenous academic and support staff in diverse roles, in curatorial, public programming, and also in development and executive roles? Is it so far-fetched to truly imagine and implement the cultural transformation of university art schools, of galleries, libraries, archives and museums, to fulfil the promise of (re)conciliation and common destinies, whereby Indigenous epistemologies and artforms are centred, and those of newcomers radiate outwards from a strong, territorially based core? Why can’t the future be informed by the past, even in Western linearity?

Had Indigenous art practices and systems of knowledge transmission not been interrupted, what would our creative expressions deal with, look like, imagine and make? While Western knowledge is structured around matter and informed by capitalism’s control and hoarding imperatives, Indigenous knowledges of the Great Ocean centre on energy and lifeforce being shared and maintained in close kinship with all living things, as everything is seen and understood as animate and having agency. These worlds do not operate in the same ceremonial–political realm. My dear colleague Lana Lopesi, writing on curatorial practice in 2016, calls for the multilingual assertion of Indigenous art practices within Indigenous knowledge paradigms:

In a way, Indigenous practice requires far more resources to receive an authentic understanding of practice. We need to produce multilingual interpretations, overcome cultural barriers and educate, as well as appreciate. (6)

In prioritising artist–curator relationships in The Commute and the two exhibitions that followed in Aotearoa New Zealand and Canada, the five curators were able to navigate the extractive logic and processes of each major institution if only for a short time, and offer real artist investment for each of the artists and contextualisation of their specific art histories transversally. Through networks of migration, trade and exchange engendered in both deep time and every day, place and travel became and remain integral to contemporary Indigenous experiences. Perhaps we can understand migration, trade and exchange as forms of commuting, and understand ourselves as commuting cultures. So, commuting also requires vigilance of the forces driving our understanding of place and movement, such as displacement, diaspora and ecological devastation.

The Commute artists and curators at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; image courtesy the Institute of Modern Art.

We’ll wear shell necklaces and barkcloth around our hips

With the coconut sennit string as the ancestors did

In all those portraits that haunt, gesture, inhabit from

Colonial museum collections on damned peoples, destined to be erased

Myriad traumas inflicted by damaging missionaries, planters, agents past and present

Ia manatua:

E mamana ‘o tātou motu \\ All our islands are sacred

‘O ‘o tātou tofi fo‘i laufanua ma ‘ele‘ele \\ Our lands are our bodies

‘O a tātou measina e fa‘apelepele iai \\ Our ancestral belongings are sovereign

E soifua pea ‘o tātou augatama i aso uma \\ Our Ancestors are always living (7)

Ma le agāga faʻafetaia ma faʻamālō atu mo lo ʻoutou lagolagoina o lenei faʻamoemoe.

Thank you for your support in this endeavour today.

Notes

An earlier shorter version of this keynote was presented in Creative Time’s Summit X | Speaking Truth in November 2019 in Lenapehoking, New York.

(1) As a political stance, in my writing I rarely italicise the expression of Indigenous languages of the Great Ocean. These words are assumed knowable by an uninitiated readership, as English is the newcomer language in this region.

(2) An excerpt from my performance and installation work titled tagatanuʻu (2017–19), unpublished multilingual text.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Teresia Teaiwa, ‘Reading Paul Gauguin’s Noa Noa with Epeli Hauʻofa’s Kisses in the Nederends: Militourism, Feminism, and the “Polynesian” Body’, in Hereniko, Vilsoni and Wilson, Rob (eds.), Inside Out: Literature, Cultural Politics, and Identity in the New Pacific, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, New York (1999) 251.

(5) An excerpt from my performance work titled L’hétérosexualité samoane est une performance chrétienne pour l’honte-temps grégorien/Sāmoan heterosexuality is a Church performance for Gregorian shame-time (2019), unpublished, untranslated text originally in French.

(6) Lana Lopesi, ‘Decolonisation Frameworks: Indigenous Curatorial Practice,’ in Runway, 27 (2015). Retrieved from http://runway.org.au/decolonisation-frameworks-indigenous-curatorial-practice/

(7) Op. cit., tagatanuʻu, 2017–19.

About the contributor

Dr Léuli Eshrāghi, Sāmoan artist, curator and researcher, intervenes in display territories to centre Indigenous presence and power, sensual and spoken languages, and ceremonial–political practices.