Running on Island Time

Winnie Siulolovao Dunn

‘Soz. Island time.’ This is what I text one of the UNSW Galleries staff members as I am waiting for my Uber that will take me to the opening of Wansolwara: One Salt Water, where I was meant to be half an hour ago. It had been a hectic morning with trains delayed by trackwork between Mt Druitt and Granville in Western Sydney, which meant I had to take a train-replacement bus that took two hours to even get to Granville. In the end, I was on time because when Islanders get together and they run the show, our energies can alter time itself. The term ‘Island time’ is also just a great line to joke around with: how can white people argue back without coming across as racist?

Wansolwara, on show at UNSW Galleries and 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art from 17 January to 18 April 2020, highlights how Oceanian peoples are connected by the sea, even from Oxford Street in Paddington to Haymarket in Central Sydney. Wansolwara is a pidgin word from the Solomon Islands meaning ‘one salt water’ or ‘one ocean, one people’. I went into the exhibition from my own perspective as a third-generation mixed-race Tongan–Australian woman from Mt Druitt. This perspective is one that acknowledges the many ways in which I feel no connection to the ocean of my grandmother and the ancestors she has shared with me by blood. The closest body of water I grew up around was a man-made pond filled with dumped Woolies trollies, plastic bags, neon-pink 7-Eleven slurpee straws and used condoms. It is hard for me to appreciate being historically connected to water as a Pacific Islander, even though I know it is the source of our mana, when the only water that moves through my everyday life is one that is manufactured, polluted and dead.

But I tried to bring myself to the water by participating in a talanoa at the Wansolwara Symposium, held at UNSW Galleries on 18 January 2020. Talanoa is traditionally held in a circular formation, to create a space for deeper conversations as each member within the talanoa brings their own histories, communities and stories. A talanoa is also held to formulate solutions to problems and to foster a sense of empathy within and between different peoples, villages and nations. To me, the circular formation of a talanoa represents the cyclical nature of water as a life-giving force that is rained down upon us, feeds our earth, our streams, our oceans and is returned skyward. The talanoa panel was held with Tongan and New Caledonian artist Ruha Fifita, Tongan–Australian artist Latai Taumoepeau and Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations artist Marianne Nicolson. We took the time to introduce ourselves through language, through village, through sacred sharks and salmon, through the urban suburbs of Sydney’s inner-west, of Western Sydney, of Aotearoa New Zealand and of the coastal mainland of British Columbia. We spoke through Cook and Columbus, the ‘celebrated’ figures of colonialism, and reclaimed our narratives. The complexity of places we were and are connected to as Indigenous women brought me to a new understanding of water. Water is not only a physical space but also a metaphor for the languid and flowing ease in which Indigenous peoples are able to converse with one another. In this way, our talanoa not only reminded me of the meaning of wansolwara but also the pain behind wansolwara that I think is most accurately articulated by the words of the late Teresia Tewia: ‘We sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood.’

Wansolwara Symposium Talanoa, left to right: Ruha Fifita, Latai Taumoepeau, Marianne Nicolson and Winnie Dunn, 18 January, UNSW Galleries; photo: Document Photography, courtesy UNSW Galleries.

Water is not only a physical space but also a metaphor for the languid and flowing ease in which Indigenous peoples are able to converse with one another.

After the talanoa, I took some time to bear witness to the Wansolwara exhibition and to feed myself back into the oneness of salt and water. I watch the video work Dark Light (2017) of Angela Tiatia, who I’ve long admired for her reclamation of the Samoan malu as something that can be both sacred and sensual. Malu means to be protected and sheltered and shows that a Samoan woman is ready for adulthood and to serve her village and her wider community. A chandelier hangs low in front of a sea of ferns and Tiatia lies naked on the floor staring back at the White gaze. Dark Light is a subversion of Paul Gauguin works such as Two Tahitian Women (1899) and Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892) which depict Tahitian women, mostly Gauguin’s multiple wives, as sexual objects of the artist’s colonial desire. I watch as Tiatia’s brown skin and black eyes reflect a sinister white light, the green background of ferns and fronds darkening. I am aware of my body, skinny and mixed race and considered pretty by the White gaze. I know my thin body and light brown skin has drawn the eyes of many white men I have known in my life and when I think of all those blue eyes, I hear my mother yelling at me, ‘That skirt is too short!’, as if a determined length of modesty in my dress would shield me from them. Tiatia’s bare chest stares back at me through a dark light, reminding me that I don’t have to be a victim of the White gaze. I can do something, I can stare back.

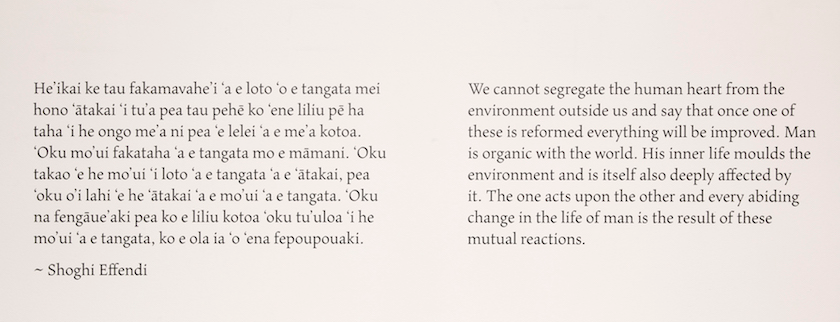

On the first floor of UNSW Galleries, to the left of the stairs, is Lototō (2016) and Koe Ngoue Manongi (The Fragrant Garden) (2019) by Ruha Fifita. Ngatu is a traditional cloth made from the bark of the mulberry tree. It is the treasure of my ancestors and today it is still a symbol of prestige, respect and cultural stories. I have never seen ngatu in an exhibition space before. The last time I saw ngatu, my grandmother was still alive. She had spread the sheets of mulberry bark across our front yard under the shade of her two-storey house in Whalan in Western Sydney. With her afro moving back and forth like a black cloud, she painted Fata ‘o Tu’i Tonga, Manulua, Kalou and Amoamokofe—symbols of the ngatu that represent our history. I would watch my nana for hours from the outer edges of the front yard as police sirens blared all afternoon, thinking about the stories of Tonga she was painting on the sacred mat. Fifita’s ngatu practice is made collaboratively, as ngatu is always made, with her extended family in Vaimalo and Aotearoa New Zealand. This collaborative effort is what gives the ngatu its spirituality, as its knowledge is not only transferred onto the mat but is also passed down from family member to family member as knowledges are told through stories about whale migrations or the roots of flowers. I walked between the two large ngatus and the words of Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Bahá’i faith from 1921 to 1957, translated into Tongan: ‘He‘ikai ke tau fakamavahe‘i a e loto ‘o e tangata mei hono ‘ātakai ‘i ta‘u pea tau pehē ko ‘ene liliu pē ha taha ‘i he ongo me‘a ni pea ‘e lelei ‘a e me‘a kotoa.’ (We cannot segregate the human heart from the environment outside us and say that once one of these is reformed everything will be improved.) That is the ngatu, the Tongan heart beating through sheets of bark with its thick, black inky veins shining like salt water.

When I see the parallel stream of Wansolwara at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, it is months later. That’s running on real island time right there. Summer is gone and its hasty goodbye has replaced nationwide bushfires with a light rain and a growing global pandemic. ‘Social distancing, social distancing!’, one of the 4A gallery officers reminds me and instead of shaking hands, he slightly bows as I bring my palm to my heart. We stand 1.5 metres apart.

The first thing I see on the first floor of the gallery is sand. Sand on the floor, sand on walls and what seems from the front entrance to be thick white sand covered in rubbish. Before I take the artworks in deeply, I am reminded that there is no salt water without sand and that the great deserts on Earth were once vast oceans. I drift to the left, where black paper is pinned to the walls like tiles displaying patterns I vaguely recognise—those of the ngatu and the Sāmoan malu—but also the /// << >> || \\\ symbols of the keyboard. Vaimaila Urale’s Manamea ma Anivanuanua (2020) brings the ancient of sand and symbols and the contemporary of language as written on a keyboard together to make cosmologies of fauna, flora and family. So many Pacific Islanders found themselves on the internet in the 1990s. I for one stayed up late into the night on my Tumblr blog on my aunt’s rundown and boxy IBM computer. As I typed to strangers over our shared obsession of Twilight, I remember how the keyboard would be covered in sticky sugar syrup from all the Macca’s cups, half-filled with fizzled-out Fanta, and how every so often my fingertips would have dead ants stuck to them. As generations of Pacific Islanders are born by, through and from the age of the internet, Urale’s artwork showcases the ways we can carry our multiple identities through the diaspora and across the Wi-fi waves.

Vaimaila Urale, Manamea ma Anivanuanua, 2020, installation view: black card and sand, 240 pieces across two walls, each wall installation measuring 5940x2520mm; commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art for Wansolwara: One Salt Water; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art; courtesy the artist.

Ebbing Tagaloa (2020) by Paula Schaafhausen, is, unashamedly, my favourite artwork of the exhibition, but at first glance it looks like a pile of rubbish. I see feathers, broken milk caps, band-aid wrappers, shells, bark, rocks and dead flies encased in a thick white mass. Such a display makes me think that maybe it isn’t so bad if I come from a place where the water is man-made, polluted and dead. I smell the flowers, coconuts and fluid gestures of ta‘olunga, a traditional Tongan dance, from my aunt’s wedding when she married a pālangi (meaning white or white-skinned) woman. Lolo Tonga! (coconut oil). What I thought was white sand turns out to be melted, solidified, melted and solidified coconut oil. A small iPad hangs sideways on a blank wall and tells me through a time-lapse video that the lolo Tonga was shaped into intricate carvings of Tangaloa, or Tagaloa in Sāmoan. Tangaloa is the God of our ancient times, known from island to island across the South Pacific. In the video, Tangaloa melts in the sun and droplets of warmed oil drip from his eyes, his arms, his belly, his penis. My body feels like someone is pushing against it as I watch the time-lapse video over and over again. I want to save Tangaloa from melting away from me, from drowning. I think of the islands in the South Pacific who still whisper his name like a prayer, even though a majority of islands are now Christian. I think about how all those islands are melting just like the Tangaloa in Schaafhausen’s carvings and we are sinking in piles of shells, rocks, feather, broken milk caps and band-aid wrappers. I think about how all this island time might one day come to a salt water end.

Wansolwara has shown that Pacific Islanders have never needed white people to speak for us, to speak about us, to speak over us. Yet they do. As a writer, it is my job to not only bear witness to the artists and writers of Oceanic communities but also to critique artists and writers who use our histories to write for us and reap the rewards. I am utterly ashamed to live in a country that has yet, to my knowledge, to publish a single novel written by an Australian of Polynesian, Micronesian or Melanesian descent. Instead, we are made to endure works like Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia by Christine Thompson, non-fiction winner of the 2020 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards. Even the title of Thompson’s Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia dehumanises hundreds of island nations and their people to a ‘puzzle’ to be ‘solved’ by the White gaze. I find her writing to be patronising in its construction of the second person:

If you [emphasis added] were to look at the South Pacific … In which we [emphasis added] follow the trail of the earliest European explorers … In which we [emphasis added] look at some of the stories that Polynesians told about themselves and consider the difficulty nineteenth-century Europeans had trying to make sense of them.

Who is the ‘you’ and ‘we’ Thompson is referring to? Why talk about how “difficult” it was for white people to understand us rather than talk about how difficult their illegal occupation throughout Polynesia was for Polynesians? This is the type of literature that is supposed to represent Polynesians both in Polynesia and in the diaspora—a dangerous narrative that stereotypes us as ancient and, in many ways, already dead.

Wansolwara’s strength is in its constant reminder that Polynesian, Micronesian and Melanesian people in Australia and beyond have always been expert storytellers of our own stories, ever since Tangaloa raised our islands from the ocean. As a third-generation mixed-race Tongan–Australian, I feel a loss whenever I think about the salt water around the island of Tonga where my nana was born, because it is a place I can never fully know. I feel like if I ever tried to look back at it I would turn into a pillar of salt, just like Lot’s wife. Wansolwara has made me realise that I haven’t lost the South Pacific Ocean, instead it moved through my grandmother, moved through my parents and moved through me in waves, and I find its cool waters in the back streets of Mt Druitt, full of dumped Woolies trolleys and plastic bags, my brothers and sisters, my aunties and uncles and my cousins and cousins and cousins. I have also witnessed the salt water that brings us together in the artworks of other Pacific Islanders I have seen in the heart of Sydney. In the midst of global warming, sinking islands, closing borders and a global pandemic, let it be known that Pacific Islanders are more than capable of creating and shaping our own narratives. I see us and our stories in the bark of the ngatu, in the white of the lolo, in the grains of the sand, in the letters of the keyboard. Let it be known that island time is now.

About the contributor

Winnie Siulolovao Dunn is a Tongan–Australian writer and arts worker from Mt Druitt.