Witnessing from afar: making sense of the Karachi Biennale

Aziz Sohail

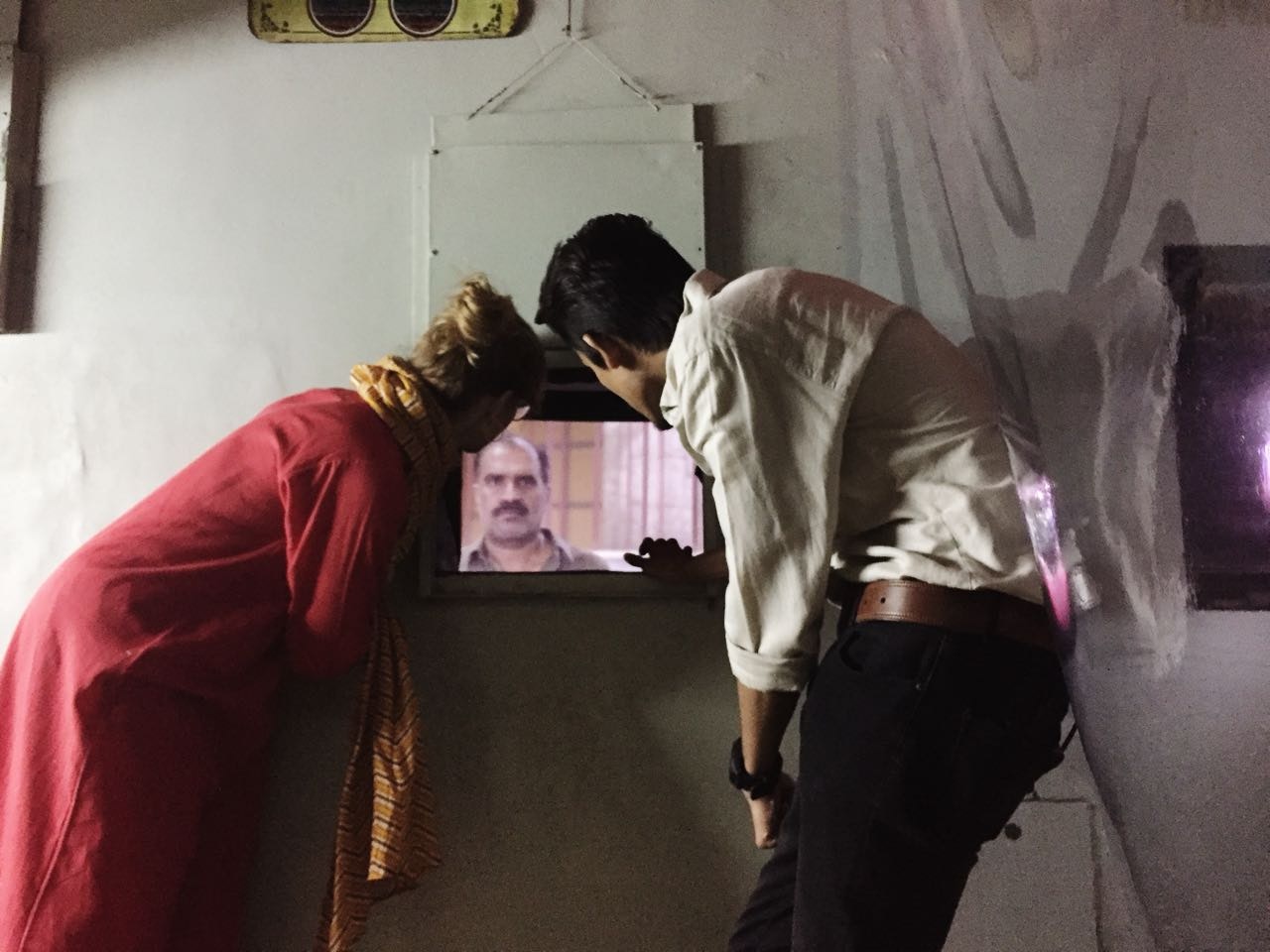

Althea Thauberger, Pagal Pagal Pagal Pagal Filmy Dunya (production still) 2017, screened at the Capri Cinema, Karachi Biennale 2017; photo: Syed Danish Azam, courtesy the artist and Karachi Biennale.

Reflections and futures

How does one begin to tell the story of Karachi, a city that dominates the global imaginary through headlines that constantly place it in the top ten most violent cities in the world (1), where so much nostalgia exists of a past which seemed to be kinder, more cosmopolitan and more beautiful? Karachi, the city that exists in this liminal space of perfect and not perfect, was host to its inaugural Biennale that took place over October and November 2017. Unfortunately, even though this is my home, I was away for the duration of the Biennale to pursue a fellowship at Cornell University investigating art making in the city from 1989–1999 centreed around a movement now loosely termed as ‘Karachi Pop’. I find it essential to state my own distance from this important moment in the city’s cultural profile, and my own involvement in the recently concluded inaugural Lahore Biennale (as the manager of its discursive program), to state that the thoughts I offer here on the Karachi Biennale (KB17) is not a traditional review but rather a mode of reflection. Indeed, my own research and understanding of the city’s history as well as my personal relationship to it allows me to understand further what KB17 might mean, such is one of the benefits of my spatial and temporal distance. In doing so, I acknowledge that like other reviews and opinions that have been expressed about KB17, my contribution will also remain a woefully incomplete task, yet my hope is that it might foster new ways of thinking about exhibition-making in a city like Karachi.

Historical sketches: a city of many stories

Today, Karachi is Pakistan’s largest city and its economic powerhouse, having emerged rapidly in a postcolonial Pakistan with large-scale migration and its designation as the nation’s capital for the first decade following independence (1947–1958). In terms of art-making, the city has had a vibrant history but opportunities to showcase art have historically been in the private and, commonly, the commercial realm. This dynamic is acknowledged by KB17’s chief curator, the artist Amin Gulgee, when he states that ‘Karachi has an active commercial gallery scene… yet there are few museums or spaces for art to be seen by the general public’ (2). No one can deny that in Pakistan, Karachi occupies the foremost location of the display of contemporary art and that historically significant exhibitions have taken place in the domain of its commercial galleries, as well as the Mohatta Palace Museum, which opened in 1999 and is run privately through an endowment. However, in the public realm the city remains acutely undernourished with barely functioning museums and public sites of display for contemporary art in particular. This is in contrast to the other important cultural and political capitals of Pakistan, Lahore and Islamabad. Lahore, due to its history and nature, retains glamour and poise through its national monuments—from pre-Mughal, Mughal and the British Raj era that includes the Lahore Museum, the Fort, the Alhamra Arts Council and others—while Islamabad retains sites of display such as the Lok Virsa Museum and the Pakistan National Council of the Arts which have been built over time due to its site as the capital of a new nation.

This is not to say that Karachi has not enjoyed moments of artistic significance and its engagement with its citizens. Despite many important modernists emerging from Lahore, such as Abdur Rahman Chughtai (1894–1975), Shakir Ali (1916–1975), Anwar Jalal Shemza (1928–1985) and others, Karachi has also been an important site of art production and discourse. It is here that the noted intellectuals Atiya Fyzee Rahamin (1877–1967) and Samuel Fyzee Rahamin (1880–1964) founded an art gallery and salon in 1947, when they moved to the city from Bombay (3). In Karachi, noted artist Zubeida Agha (1922–1997) ‘fired the first shot of modernism with her exhibition in 1949’ (4). Other artists, such as Sadequain (1923–1987) (5), undoubtedly one of Pakistan’s most prolific and well-known artists, made Karachi his home and the city continued to be the birthplace and early inspiration for many artists such as Rasheed Araeen (b. 1935), the latter going on to found Third Text (6), perhaps the most important scholarly journal of art in postcolonial contexts. Similarly, Ismail Gulgee (1926–2007), incidentally the father of the KB17’s chief curator, also resided in Karachi and was an influential figure. Despite this, the city never had an accredited public art school until 1989 when the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture was established, even though older private avenues for the education of artists, such as the Karachi School of Art founded in 1964, had operated as a non-tertiary institute offering diplomas and certificates in art.

My research, which looks at Karachi in the 1990s, posits that the city is a particularly rich and provocative site of art production. In that decade, emerging practices—in particular led by artists Durriya Kazi, David Alesworth, Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi—responded to questions of the place of the vernacular in art-making, the city as a site and canvas for making, and new modes of pedagogical instruction and collaborative practices that had before not been fully explored in Pakistani on a large scale. The main avenues of collaboration between Karachi-based artists occurred through two key early projects. In 1992, Durriya Kazi initiated Art Caravan in which she delineated the body of a truck as a traveling exhibition with her students from the Karachi School of Art. The students created work on the truck, with the UK-based artist David Alesworth also contributing. In this regard, Kazi’s work represents one of the first key engagements in bringing art beyond the white cube or a private gallery space and into the public realm. The second key collaboration was Heart Mahal installation (1996), an ambitious project for the exhibition Container 96: Art Across Oceans staged in Copenhagen in the year the city was deemed the European Union’s Capital of Culture. This project brought together various urban craftsmen living and working in Karachi—truck artists, metal workers, light installers and others—to collaborate with Durriya Kazi, David Alesworth, Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi on a large installation that would borrow heavily from the vernacular and popular imagery in the city of Karachi, especially as found on street signage, popular magazines and children’s magazines and urban materials used for decoration and celebration by Pakistan’s non-elite. These artists were also involved in teaching at institutions and many of their students, including Huma Mulji, Asma Mundrawala and Saba Iqbal, would also go on to develop important work around similar concerns and initiate important exhibitions which looked at the city, especially the 1999 exhibition Cityscapes presented at Karachi’s Frere Hall Gallery.

How does one begin to tell the story of Karachi, a city that dominates the global imaginary through headlines that constantly place it in the top ten most violent cities in the world (1), where so much nostalgia exists of a past which seemed to be kinder, more cosmopolitan and more beautiful?

The 1990s is also the decade that rests in the collective memory as Karachi’s most violent epoch. Newspaper clippings from the Herald in 1994 and 1995 refer to Karachi as a city of death with over 1000 and 2000 annual violent deaths respectively. The city became a site of ethnic violence, perpetuated with frustrations and economic anxieties following the fall of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamist dictatorship from 1978 to 1988. At this time, the national image of the coastal city transformed from a cosmopolitan economic hub in Pakistan to a city beset with continuous ethnic and sectarian unrest. Contemporary Karachi has never been truly able to shake off this part of its history and, indeed, has witnessed continuous episodic periods of violence, most recently from 2007 to 2013. It is perhaps in response to this reality, or in relationship to it, that so many artists have begun to address the city as subject, even as their works don’t necessarily fit into neat categories for consumption in the West. It was in Karachi that Vasl Artists’ Association (as part of the broader Triangle Arts Network) was founded in 2001, led by artists such as Naiza Khan, Amin Gulgee and Lahore-based Lala Rukh among others (7). The collective brought important international artists to Karachi through residencies and other events. Vasl’s activities became and continue to be an important means by which the local community opened up to global discourse and influences, in turn supporting many nascent artists in their practice locally and globally. In addition to the artists already mentioned, emerging contemporary practitioners such as the Tentative Collective, Omer Wasim and Saira Sheikh and Karachi Art Anti-University (led by Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani) continue to address concerns around the urban in their practice.

In all of this history and multiple narratives it is truly a difficult task to begin to unpack the layers of the city. This concern seemed to be on the mind of Amin Gulgee as he formulated his vision for KB17, himself having a long history of initiating important exhibitions in Karachi, beginning with Urban Voices, which had four iterations from 1998 to 2001 at the city’s Sheraton Hotel, and more recently Dreamscape (2014) at Amin Gulgee Gallery that featured performances and installations by 50 artists (35 based in Karachi), co-curated with Zarmeene Shah, the curator at large for KB17. Under the central theme of Witness, Gulgee noted that KB17 proposed that ‘we all bear witness to our times and ourselves, both in the present and the past.’ Witnessing violence seems to be a central concern for the curator, such as when he notes that the city ‘bore witness to partition’ and calls it a ‘bruised city’ (8). In this regard, given the history of the city and its art historical trajectory, the Biennale seems to be particularly poignant and needed by its citizens. KB17 gave a nod to the nature of this sprawling metropolis by ‘clustering’ different venues. A key problem of a city like Karachi is that it exists without a cohesive network of public transport—the largest city in the world to do so. Navigating the city thus requires an approach that is usually arduous and messy. Spread across 14 sites, the Biennale forms different clusters. As noted by Zarmeene Shah: ‘In the spatial configuration of the city, the sites could be divided into four clusters, with the one forming in and around Saddar, the old city center and business district of Karachi, representing what could be viewed as the central node.’ (9).

Given the history of the city, with so many divisions and ruptures, the Biennale existed under great inclusivity with over 180 participating artists. While this disrupted and loosened the curatorial theme itself (some may argue that the theme was so broad as to fit all works within it, though this is a commonplace as far as global biennales are concerned), KB17 also formed key international relationships with practitioners from the Global South, such as with artists and curators from South America and Africa, in addition to Europe. The spirit of inclusivity and generosity offered the Biennale’s organisational team was self-evident to many observers, distant or near, via opening events and social media; Deborah Robinson, a visiting curator from the UK noted over email to me that KB17 was ‘warm, welcoming and celebratory’ (10). For a city with a thousand stories, welcoming so many voices seemed the correct way forward for a nation’s first ever Biennale.

With such a rich participation of artists, it becomes difficult to mention or give weight to any over the other. For the purposes of this text, and given my own research interests, I now navigate through three key works that garnered my interest from afar as particularly successful examples of acts of bearing witness to a city through site-specific interventions: Althea Thauberger in Capri Cinema, Madiha Aijaz in the Library of Jamshed Memorial Hall, and Huma Mulji at Pioneer Book House. Cartographically, these three works were situated on M. A. Jinnah Road, the city’s main artery leading to the port, in a short span of two kilometers, that cumulatively activated stories of the city through its decaying and suspended civic institutions. The three sites, which transition and exist between realms of the colonial, modernity and the present contemporary through different registers, are a good example of how the city of Karachi as a site becomes a witness for pasts, commenting on the present but also imagining futures.

The Capri Cinema, Karachi, 2017; photo: Humayun Memon.

The Cinema

We begin at the Capri Cinema for Pagal Pagal Pagal Pagal Filmy Dunya (2017), a work created by Vancouver-based artist Althea Thauberger in collaboration with many local artists over a span of several months. The Capri Cinema has a storied history, one whose symbolic import lent itself to Thauberger’s work perfectly. Opened in 1968, the Capri heralds that it enjoys ‘nearly half a century’s worth of glamorous history during which it has been synonymous with high quality films, all-encompassing sound, and enchanting picture quality, all housed in a comfortable, friendly and inviting family environment’—in recognition of a past when multinational multiplexes were non-existent (11). Its modernist architecture establishes it as an important cultural icon and, concordantly, the Capri has fostered many important releases from Hollywood and Lollywood. Tragically, it has also been a site of violence in many instances, most recently in 2014 when along with two other cinemas in the same area it was burnt during a protest led by Islamic extremists. While the other two cinemas have never recovered, the Capri was renovated and revived—in doing so, the Cinema rests as a proud and stalwart witness to history, always under threat of erasure but ever present.

Althea Thauberger’s film opens with shots of the Capri Cinema itself, as it seems to re-open for a new day of activity. The viewer is taken into the screening room, with its faded red carpets and seating where a sweeper is cleaning it early in the morning; these spaces would have been physically experienced by the Biennale viewers themselves, thus placing them within the literal screening itself. The sweeper begins:

My dear city Karachi.

The whole of Pakistan is fuelled by my dear Karachi.

All the peoples of the world come to Karachi.

Everyone is fed in Karachi.

Is it still okay to blame Karachi?

Come, now, Karachi, let’s tell everyone what was and is Karachi.

Everyone’s mother is Karachi.

Such a call seems to feed right into the premise of the Biennale as a way of telling many stories, while also speaking of the history of Karachi as a space of contestation and self-sufficiency. The film continues with shots of individuals, perhaps patrons of the Capri, performing and speaking on the screen, as if calling for someone to hear with no response. Later, the work shifts toward documentary-style storytelling, where the owners and employees of the Cinema chart a history of the site, explaining its architectural features, the way it functions as a part of a larger economy and its audiences. Thauberger noted in her conversation with me that ‘the cinema is an object reflected back on the viewer’ (12).

By highlighting the complex history of the Capri Cinema in tandem with projecting within and upon its space the symbolic history it occupies for many of its patrons, Thauberger activates this site as a witness to history itself as relayed and told by its custodians and viewers. Through her work, daily occurrences seem as but a scene in a longer cinematic work that in turn allude to the title itself which translated in English is ‘Mad Mad Mad Mad Filmic World’ (13). In doing so, Thauberger poetically and poignantly lends voice to those through whose labour the Capri has survived as a prominent cultural voice and witness in the Karachi, despite many challenges.

The Library

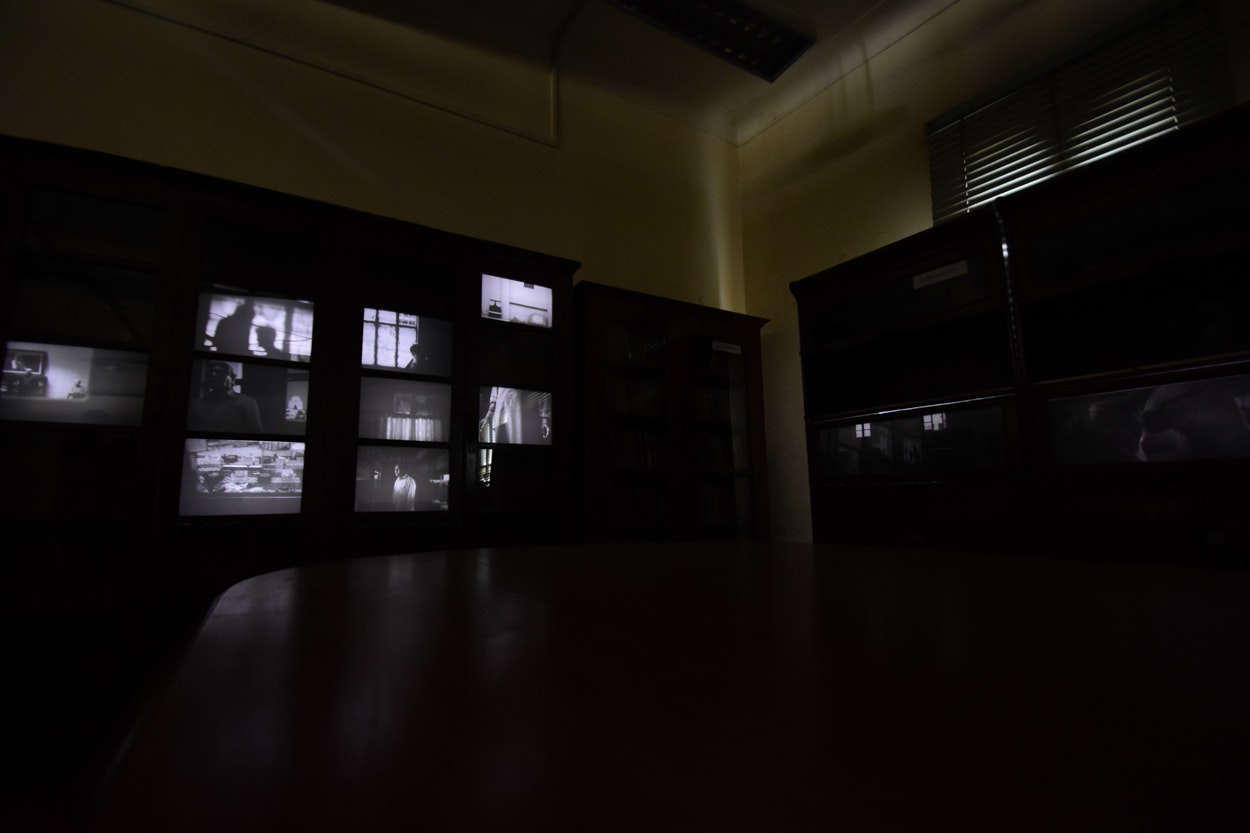

Karachi-based artist Madiha Aijaz’s presentation of her ongoing project documenting public libraries in the city was showcased at the Jamshed Memorial Hall. Like many other spaces which served communities, libraries have increasingly become limited due to closures or fossilisation since the advent of our digital age. Aijaz’s work, a series of photographs and a video installation under the title These Silences Are All The Words (2017) documents this truth by also complicating it. A central element of her work are portraits of librarians displayed as black-and-white backlit images. Aijaz aims to document these individuals, whom she calls ‘custodians of knowledge’, as a means to study the city through their eyes. This is especially poignant as many of these libraries do not have digitised holdings and memory of their contents plays an essential role in being able to guide readers. In this way, Karachi’s libraries become a way to read the cultural history of the city itself. In conversation with the artist, Aijaz tells me that there are 126 libraries in Karachi that span from general access to specialist collections. Many are in disarray, such as the library at Frere Hall which is another site of the Biennale and a building that was originally intended to serve at the city’s Town Hall upon its completion in 1865. Karachi’s libraries therefore exist and are functional but do so under the slow decay of time. They are neither fully alive nor are they yet dead.

These Silences Are All The Words seems especially momentous installed at the Theosophical Society Library (one of the photographs documents the librarian there as well) given its history in the city. Founded in 1896 by Annie Besant (1847–1933), the prominent British activist and writer who was a supporter of Irish and Indian self-rule, the Society has long existed as a ‘unique platform where likeminded persons of any religion or faith get together to understand and foster moral, ethical and spiritual values and principles’ (14). The president of the Society, Dara Mirza, was assassinated in 2007 and since then the Library’s patronage and prominence has been considerably diminished. Significantly, the literature in its collection that may risk being deemed as reactionary has over time been hidden from public view. In placing this work in a space under threat of erasure, Aijaz’s act is an assertion of the power of such histories and their constant evolution.

The Bookshop

The Pioneer Book House, established in the 1940s, is regarded as Karachi’s oldest bookshop still in operation. This site hosted Bristol-based Huma Mulji’s installation Ode to a lamppost that got accidentally destroyed in the enthusiastic widening of Canal Bank Road (2011–2018). Given the work’s sculptural intervention spanning all three levels of the bookshop, this title speaks volumes. Referring to a central road in Lahore whose widening led to many protests and Supreme Court cases, the artist comments on a statist approach to heavy development as showcased through the building of roads, flyovers and freeways that are suddenly obsolete years later when priorities shift. Pakistani cities over the last twenty years have seen an upsurge in neoliberal capital and a parallel desire to reshape the city in ways that most often, though not always, favours short-term private gain for the elite over long-term civic good. The urban fabric of Lahore, in particular, where Mulji lived for many years, has been reimagined through this approach to development. In this regard, the past, as showcased through historic architecture or sites, is not important and can be sacrificed—unless it functions as a means for the state to further nationalism. Hope remains, however, as evidenced by Muji’s lamppost with flickering light that symbolically alludes that it is ‘gasping for life… refusing to die’ (15).

The presence of Huma Mulji’s artistic intervention within Pioneer Book House underscores the site’s precarious existence as it is presently under threat of shutting down due to decline in trade following the slow shift of the city’s cultural centre away from its location in Saddar, a central neighbourhood of the city. The bookshop was saved through the efforts of many individuals in the city and principally led by Maniza Naqvi, a writer based between the USA and Karachi. Ode to a lamppost that got accidentally destroyed in the enthusiastic widening of Canal Bank Road raised controversy during the Biennale when the artist was accused by many prominent individuals in the cultural sphere, including writers, artists and intellectuals of vandalising the space (16). These critics regarded the work an almost violent intervention given one of its sculptural components was installed such that a pole runs through each of the building’s levels, making navigation of the space difficult. In this way, Muji’s work alludes to how the life of citizens is affected and negotiated through developmental projects, while also acting as a critical commentary on the folly of preservation—destruction, after all, is perhaps the first inevitability with the march of progress in the postcolonial state. These inherent metaphorical tensions in the work are not in paradox but are instead in constant negotiation with each other. The fact that the work raised such uncomfortable questions could be seen as a sign of its success, given the placement of this bookshop which itself occupies its place in an area which used to be culturally prominent but is now situated in the congested commercial centre of Karachi rather than its cultural heart.

Huma Mulji, Ode to a lamppost that got accidentally destroyed in the enthusiastic widening of Canal Bank Road, 2011-2018, installed at Pioneer Book House as part of the Karachi Biennale 2017; photo: Humayun Memon, courtesy the artist and Karachi Biennale.

Belonging to my city

Departing the Pioneer Book House, I turn back and head towards home, only this time I happen to enter Numaish Chowranghi, a busy intersection in the city and one of the ending points of M. A. Jinnah Road. Towards the left is Britto Road. This colonial era road is where I grew up. Over time, Britto Road has transformed from an upscale leafy quiet street with massive bungalows where Christians, Hindus, Parsis and Muslims used to live to a more middle-class neighbourhood with apartment blocks and commercial sites that reflected the diversity of a postcolonial Karachi. My family left this part of the city just a few years ago—it had increasingly become the site of protests and blockades given its closeness to important Shia and Sunni religious sites and its use as a site of protests and sit-ins as well as political rallies. My experience of Karachi, and how its populations shift and evolve, perhaps mirrors the ways in which artists have spoken about the city itself through this Biennale, and beyond. As a witness to the city through a personal family history, my relationship to these sites and the Biennale seems particularly potent; in activating this relationship to the city for its inhabitants the Biennale has begun dialogues that will only deepen over time.

Karachi Biennale 17 was presented from 22 October – 5 November 2017.

Notes

(1) For example, Asad Hashim ‘Karachi’s killing fields‘, Al Jazeera, 6 September 2012.

(2) As quoted in ‘Message from the Chief Curator’, Karachi Biennale 2017 Guide

(3) Saadia Qamar, ‘The ever lingering fate of the Fyzee Rahamin Art Gallery’, The Express Tribune, 10 July 2017.

(4) Iftikhar Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2010) 114.

(5) Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, also often referred to as Sadequain Naqqash or simply Sadequain.

(6) Araeen founded and edited the journal Black Phoenix, which in 1989 was reconfigured and renamed Third Text.

(7) Karachi Biennale 2017 Guide, op. cit.

(8) Naiza H. Khan, ‘On Vasl’, Universes in Universe, May 2007. Accessed 16 May 2017.

(9) Zarmeene Shah, ‘The inconceivable: on the first Karachi Biennale’, Critical Collective, November 2017.

(10) Email exchange with the author, 1 November 2017.

(11) ‘About us’, Capri Cinema.

(12) In conversation with the author, February 2018.

(13) The title of the work is inspired by the Hollywood comedy movie It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World which was released in 1963 and was screened at Capri Cinema. While researching the Capri Cinema for her work, Thauberger came across posters and information about this movie within the Capri’s physical archive,

(14) See Theosophical Society Karachi.

(15) As quoted on KB17 website.

(16) Hamna Zubair, ‘How an exhibit at the Karachi Biennale stirred a storm in a pre-partition bookshop’, Dawn, 6 November 2017.

About the contributor

Aziz Sohail is an art curator, writer and researcher who has been working in Pakistan for five years.