Knowing Modern and Contemporary Asian Art

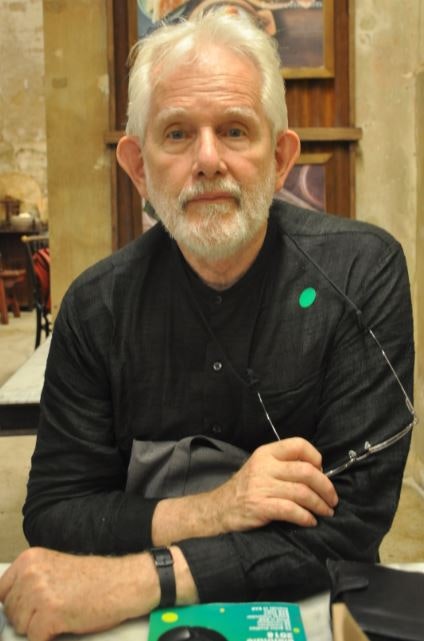

John Clark

There has been quite a lot written and discussed about Asian Art and Australia (2), much about the historical perception of Australia’s place in the region and Australia’s ‘white’ self-perceptions (3), and some, mostly recent and initial work, on the teaching of Asian art history over time (4). Rather than simply re-iterate the knowledge and opinion that this work has generated, I will present one view of what the situation is now and may require in the future.

Asian art history education today is a very mixed field linked to both art history teaching departments and the structure of knowledge at state and national galleries, as well as to independent curators who are not directly affiliated with any given institution. At universities, one can note the steady production of PhDs where a member of staff has been able to develop a program, but there is an absence of continuity of appointments in many tertiary institutions. Prospective scholars and curators seeking a PhD must carefully look around and appraise the quality of researchers, their attachment to the university in question, and the supervisor’s willingness to see through the work of conference organisation and subsequent publication.

But these are questions of art history education embedded within a broader problem. As an Australian Southeast Asian historian once remarked, ‘Australian politicians wake up every twenty years and [re-]discover we are in Asia’. The same feature of Australian administrative elite perceptions also applies to museum directors who go hot and cold on Asian art exhibitions and on having specialist Asian art curators. That is, unless like the late Edmund Capon, they have made an effort to becoming specialists in an Asian art history field (5). Despite the renown of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art it is a fact that the excellent collection the Queensland Art Gallery has built up has not often been shown outside Queensland. Indeed, it is a contemporary Asian art collection of note, a private gallery devoted to contemporary Chinese art, White Rabbit in Sydney, that has determined to show parts of its collection outside Sydney. This has not been the case for other public collections in Brisbane, Canberra and Melbourne. Few, except maybe two or three specialists would be aware that between the holdings of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the University of Sydney and the National Gallery in Canberra there is a world-ranking exhibition of modern Chinese prints yet to be organised. In the case of pre-modern art, neither have we seen collected masterwork exhibitions in particular fields like Chinese ink painting or Japanese screen painting which could tour nationally. We have, I daresay, several museum collection works in both Melbourne and Sydney which would be National Treasures or Important Cultural Objects in Japan, but they are only brought out from time to time as an object belonging to the collection of one museum rather than seen as part of a collective inheritance between Australian institutions.

Ono Tadashige, Shigaisen (Street Battle) (1930), woodcut on paper, 30.5 x 23.0 cm. University of Sydney Art Collection. Purchased with funds from the Dr M. J. Morrissey Bequest Fund in memory of Professor A. L. Sadler 2007. UA2007.5 © Estate of Ono Tadashige.

As an Australian Southeast Asian historian once remarked, ‘Australian politicians wake up every twenty years and [re-]discover we are in Asia’.

There is no space here to analyse the issue of shared distribution of insurance guarantees at the level of state governments and the Commonwealth that constrain the kind of ‘blockbusters’ which museum directors and their attendant publicists seem to require. These are in any case tied by state budgets and perceptions of cultural spectaculars of a periodic and opportunistic basis that these days can tie tourism sector agendas to cultural ones (6). Nor can one reliably examine the relationship between contemporary art curators in Australia and contemporary art from other countries in Asia. These types of showcases can be effective if rather predictable, such as the size of the attendance for the recent Ai Weiwei (paired with Andy Warhol) and Cai Guo-Qiang (paired with the terracotta warriors) exhibitions in Melbourne. Some important issues surrounding such exhibitions would appear to be beyond current curatorial competence: Miyajima Tatsuo, whose own solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) in 2016–2017 was presented under the umbrella of the NSW Government’s Sydney International Art Series of summer programming, once notoriously wrote in Japanese that ‘zero’ was a Western concept. This ideological fatuousness, linked as it is to a kind of ultranationalist, even crypto-fascist cult in Japan, was not so far as I could see mentioned by the curators at the MCA.

But organisation of such exhibitions does indeed engage mass taste which is precarious and often kitschy and very, very predictable. High-end, indisputably ‘crass’ consumerism requires the putative car user to distinguish between a Mercedes and a BMW, and in art all our cultural perceptions are conditioned by a rather forlorn search for such a materialised celebrity and distinction. This ‘wow’ factor involves very little reception effort by the audience and such mass appraisal (or the prior judgement of the museum marketing director) cannot reward much investment in curatorial careers. Furthermore, Asian art curators have frequently been absorbed into museum departments for contemporary or ‘international’ art when the other contemporary art curators have in most cases little knowledge of Asian art cultures except what is purveyed by accepted positions in international art press and the circuits it follows. There are sometimes academic art museums which provide careers for trend-breaking and innovative curators in exhibitions such as those in Chicago at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago which recently showed Tang Chang (Chang Sae-Tang) and the Art Institute of Chicago with their first American institutional survey of the work of Zhang Peili and a thoroughly comprehensive exhibition of Japanese photo-books. But these would appear to be the exception even in North America, and we have not seen their equivalent in many Australian-authored exhibitions (7).

The university and public libraries in Canberra, Melbourne and Sydney are reasonably well equipped to service undergraduate courses but may in some cases take their research-level holdings for granted. The Guggenheim Museum in New York recently exhibited in glass cases documentary materials from 1980s China which have been on open shelves at Fisher Research Library in Sydney for around 15 years. A donated collection of contemporary Japanese art catalogues at Fisher is even consigned to off-site storage.

Speakers from the Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia conference, presented by the Humanities Research Centre and School of Art and Design, Australian National University (ANU), in conjunction with the National Gallery of Australia and supported by the Research School of Humanities and the Arts ANU and the ANU Indonesia Institute, 24 June 2019. Photo credit: Emeritus Professor, David Williams, ANU. Top row (left to right): Melati Suryodarmo, Bianca Winataputri, FX Harsono, Caroline Turner, Alia Swastika, Chaitanya Sambrani, T.K. Sabapathy. Bottom row (left to right): Tisna Sanjaya, Carol Cains, Christine Clark, Jaklyn Babington, Elly Kent, Zico Albaiquni.

Universities tend to behave as if individual scholars rather than their field of knowledge carry continuities, very often being allowed to carry them away when they leave an institution.

Among other constrictions of institutional learning are that in compensation for a PhD qualification the research student has to comply with the methodologies and sometimes l’esprit du temps of a cohort of other postgraduates and their supervisors. They may not be aware that their frequently post-Saidian and post-colonial schemata do not fit various Asian contexts, let alone that Asian concepts and contextual positioning of the modern and contemporary be founded on quite different historical bases than those conceptually acceptable in Euramerica. Nevertheless, students have now the capability of linguistic acquisition as part of their PhD work and this requirement, although not always easy to meet, is different to the past when it was forbidden by scholarship regulations for Australian Postgraduate Award research students to undertake such ‘vocational’ language training in parallel with their research work.

Training in art history relies on the circulation of ideas over time, as much as the appraisal of artworks requires their circulation via their ability to attract curatorial attention or, realistically, on the facture of works allowing appraisal in monetary terms via the art market. There is little doubt that the first cohort of PhDs in modern and contemporary Asian art in Australia have done very well because the cycle of circulations of ideas and works in the academy and in the museum have been opened up by the saturation of both the commercial and curatorial markets with well-known local or international modern art. This may have contributed to what might be seen as a systemic requirement to open up new avenues, or to place new circuits of circulation into the realm of ideas and collection. The last ten or so years of postgraduates were qualified just in time for a new opening of art institutions, and for a new awareness by audiences generated by travel to and cultural transfer from Asia. Fortunately, all the supervisees I advised studied their language well and melded carefully with the art societies where they did research. This cultural facility might have been imbibed in an Australian multicultural context and, combined with intellectual training in art history, has left them in good stead to maintain their interest rather than let it desiccate into a rather too predictable atrophy brought on by general curatorial ignorance.

It may be that the character of those who study Asian art now, whether ancient or modern, demands a kind of intelligence but also cultural persistence which is not found among all art history researchers. But in this age of ‘independent’ scholars and curators let us not forget art history and curation are pre-eminently institutional practices. These actors work with generally set rules and places, however much it may be pleaded these are unconventional or somehow untrammelled practices. They also work with trained cohorts of thinkers who are surprisingly interlinked by virtue of their certifying institutions. Sometimes this can be a help when the institutions begin to support a new field like modern and contemporary Asian art history, as in my own experience. At other times it can be a hindrance, mostly when staff change, move, or even retire, and are not replaced in kind: universities tend to behave as if individual scholars rather than their field of knowledge carry continuities, very often being allowed to carry them away when they leave an institution. Some professorial appointment committees act rather like the jury for shows seeking new and suitable talent rather than those capable and willing of covering a field for which there is a proven present and future demand. Professional associations can to some extent counter institutional closure, like the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand or the Art Historians Association in Britain. These do act by their publication of journals to counter professional narrowness, although the associations too have their côteries of ‘friends at court’, and often in the guise of appraising professional prominence for refereed articles can act to exclude some scholars from centres of decision-making if they otherwise have no institutional network (8).

Such considerations aside, the art history discipline has since the 1980s for various reasons broadened both its ideas and the recruitment of its personnel, so there is a very good prospect of new entrants with a secure Asian art history background being ahead in various career paths which are otherwise too easily deflected by fashion or blocked off by ideology. The problem for all scholars and curators is avoiding the various quagmires of mere careerism. If the material is new to a discipline or to exhibition display, if the approaches are solid or bravely innovatory, if there is a secure linguistic skill and a deep other-cultural knowledge base, then their work will stand long after the particular opportunities have gone which may have occasioned it.

Curator and writer Freya Chou, talking with students from the University of Melbourne Advanced Art Fieldwork, Contemporary art in China intensive at Parasite, Hong Kong, July 2019. Photo: Claire Roberts.

Since the volume and direction of the flow of art works and the currency of those who interpret or introduce contemporary art has changed since around 2000, we may expect there to be a future to art historical research on areas which were once outside or marginal to ‘normal practice’. Whether the institutions which service this knowledge and its distribution have moved in quite the same way remains to be seen. We can expect to see new modes for old styles of place-keeping which the very supposed radicality of changes may have been thought to supersede. But because Asian art history, in the Australian context at least, especially involves the modern and the contemporary, and is particularly taken up with the new or the culturally other, or is in itself brought forward by an intellectual self-distancing from habitual modes of thought and practice, it is unlike and even disruptive of comfortable art history within a received Euramerican frame.

To slightly reinforce this conclusion, such an art history and its accompanying curatorial practice directly concerns issues of the self and its cultural others, and how these inter-relations are perceived. It cannot function by a comfortable lapse into chauvinism or whiteness, and thus has important consequences for the self-perception of Australians, who despite the atavistic predilections of some of our political class and segments of our educational and museum systems, long ago ceased living in a binary world.

Notes

(1) Professor Emeritus Asian Art History, University of Sydney, I retired in 2013 after teaching at Sydney for twenty-one years. I was responsible for or otherwise involved in postgraduate completions including 23+ PhDs, and among other writings published five single-authored books, five edited collections of papers and wrote or co-curated three major catalogues.

(2) See Darryl Collins ‘Asian Art in Australia’, Art & Australia, 30:3 (Autumn 1993); Darryl Collins, Asian Art and Australia: 1830s-1930s (M.A. diss., Australian National University, Canberra, 1992). On Asian-Australian artists see the audio recordings for Asian-Australian Art Now: Positioning the Fields, a workshop with presentations by many artists and curators at Gallery 4A, Sydney, in September 2008, which was co-organised by Thomas J. Berghuis and Aaron Seeto; John Clark, Australian Art and Asia -Then and Now’, Occasional Paper no. 19 (Sydney: Research Institute for Asia and the Pacific, University of Sydney, July 1992); John Clark, ‘“Asian Art” and Australia’, in Jaynie Anderson, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Australian Art (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2011) 217–230; John Clark, ‘An “Australian” Creative Space: Where is Australian-Asian Art Now?’, Contemporary Visual Art & Culture, Broadsheet, 40:2 (June 2011), 90–95 [edited re-publication]; James Beattie, Richard Bullen and Maria Galikowski (eds.), China in Australasia: Cultural Diplomacy and Chinese Arts since the Cold War (London: Routledge, 2019).

(3) On the historical perception of Australia’s place in Asia see David Walker, Anxious Nation: Australia and the Rise of Asia, 1850-1939 (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1999); and David Walker, Stranded Nation: White Australia in an Asian Region (Crawley, WA: UWA Publishing, 2019). Unfortunately, neither of these books refers to the role of art in representing or changing cultural understanding. On the function of ‘whiteness’ in Australian self-perceptions see Ghassan Hage, White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society (Annandale, NSW: Pluto Press, 1998); and Ghassan Hage, Against Paranoid Nationalism: Searching for Hope in a Shrinking Society (Pluto Press, 2003). A review of knowledge of Asia is Michael Dutton and Deborah Kessler, ‘Australia’s Asia: An Illiterate Future?’, China Heritage Quarterly, 19 (September 2009). See also Michael Wesley, Building an Asia-Literate Australia: An Australian Strategy for Asian Language Proficiency (Nathan, Qld.: Griffith University Asia Institute, May 2009), a report not acted upon.

(4) See the Special Issue edited by Stephen Whiteman and Olivier Krischer, including my essay, ‘Asian Art History in Australia: its functions and audience’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 16:2 (2016) 202–21.

(5) Edmund Capon OBE, AM (1940–2019) was Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, from 1978–2011. His career as an Asian art scholar began in 1973 when he was assistant keeper, Far Eastern section at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Additionally, he served as Chair of 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, from 2014–2019.

(6) For example, Andrew Taylor, ‘Celebrity or artist? How Yoko Ono sparked a fight between NSW bureaucrats’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 August 2019.

(7) Except, perhaps, Modern Boy Modern Girl in 1998 at Art Gallery of New South Wales, curated by Jackie Menzies, Ajioka Chiaki, John Clark and Mizusawa Tsutomu, or likewise in 1998, the Korean textiles exhibition Rapt in Colour: Korean Textiles and Costumes of the Chosôn Dynasty at the Powerhouse Museum (Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences), Sydney, curated by Claire Roberts and Huh Dong-hwa.

(8) Sometimes it is simpler for those excluded to set up new field-defining journals such as ARTMargins (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press) or Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art (Singapore: National University of Singapore); the former excluded by what one may call the October mentality, the latter by the infection of mass-journalism and gallery commercialism one sees in ArtAsiaPacific nowadays when compared with its earlier 1990s innovative editions in Australia.

Addendum: Teaching of Asian Art History in Australia, a brief analysis of some figures and issues

John Clark, 1 September 2019

This analysis accompanies the downloadable spreadsheet of Asian Art History teachers across Australia from a list I drafted in August 2019 and a short paper, ‘Knowing Modern and Contemporary Asian Art’, I wrote by invitation for issue 7 of 4A Papers, November 2019.

Current teaching and research

The teaching of Asian Art History in Australia falls within traditional art history departments but also overlaps the disciplinary areas of Archaeology, Art Theory [for artists], Critical Theory, and Curatorial and Museum Studies [for curators], in some institutions. I shall treat these flexibly as a whole while recognising that there may be considerable variation in approach between different departments. Several courses and research interests are supported by museum curators from time to time, depending on local need and available specialists.

Certain undergraduate patterns and staff research foci are prevalent: most attention is given to modern and contemporary Asian art, and the most fully covered areas are China and Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia, Myanmar and Singapore. The China field has certainly generated intellectual output recognised widely outside Australia. South Asia has also been the focus of art historical teaching and some research, mostly at the Australian National University. There has, from time to time, been strong interest in Islamic art in South Australia; this also might be expected to grow with recent teaching and curatorial staff appointments at the University of Sydney, and the given scale of immigrant populations with an Islamic background.

Gaps

However, despite the obvious strength of some research, research library holdings and museum collections, Japanese and Korean art has not received the art historical attention which might be expected and which in the Korean case a significant local immigrant population might support. Surprisingly, Brisbane has no course in Asian Art History, even of modern and contemporary Asian art. Neither have the pre-modern Chinese and Japanese painting and some sculpture and ceramics in public and private collections in Adelaide, Canberra, Melbourne and Sydney been the subject of much higher research and teaching, although good curatorial work has been done for several exhibitions. In the modern and contemporary Asian art fields, there has not yet been the prominent development of Cultural Studies, Critical Theory and History of Asian Photography studies devoted to Asian new media or new forms of art interface with a digital and post-digital society. With some freeing of institutional boundaries, and perhaps more co-supervision across departments and institutions, this field could develop greatly.

Future scale

As a kind of historical template, from 1995–2013 there were approximately two PhD graduations per year in Asian Art History in the Sydney area. This involved a PhD cohort which by the mid-2000s resulted in 40% of all postgraduate by research seminar presentations in Art History at the University of Sydney. This gives a rough benchmark for the scale of a research community in Sydney institutions overall which can be generated through 4–6 curators, 4–5 university teaching and research staff, and 15–20 research students. It is conceivable that this level of activity could be paralleled in Melbourne and in varying degree in Adelaide and Brisbane.

About the contributor

John Clark is Professor Emeritus in Art History at the University of Sydney where he taught for twenty-one years.