APT9: The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art as practice

Annabelle Lacroix

Zico Albaiquni, various works, 2016-18, pigment, oil and giclée on canvas; photo: Natasha Harth, The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9), Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; courtesy the artist.

To write an exhibition review is to believe in a ‘conspiracy of objects and meanings’ (1). Perhaps this is due to the necessary curatorial ambiance of exhibitions, but also because language is locked to this conspiracy, playing tricks on you with a slip of the tongue, or other slippages—opening new meanings.

I quite like the idea of a conspiracy in relation to art objects, thinking that singular works of art in rooms, and the words that represent them, could be plotting something. Writing about The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), I decided to focus on this conspiracy to weave immaterial and transgenerational connections that these art objects can produce, a generative process that the APT has excelled at since the project’s first iteration in 1993. Excluding the third edition of the APT in 1999, the only themed iteration of the exhibition, the APT has remained a geographic survey whose boundaries have kept moving in relation to the political and cultural context of the times. Perhaps because of its lack of thematic framing from the top down, the institution allows for greater agency in the objects themselves, and in the viewer in front of them. Instead of a ‘point of view’ given through a curatorial theme, the institution executes its power through a methodology of research and relationship building within the region. Moreover, the APT has forged a particular curatorial practice for itself, as well as a practice of ‘looking’ for audiences, one that troubles the traditional boundaries between notions of contemporary, traditional craft and fine art. Both practices are linked, and pay particular attention to local specificities, as well as the impact of modernism and the cultural knowledge and practices that transcend nationhood. With each Triennial, informal sub-themes emerge like veins in the museum. Throughout the Triennial’s ninth edition there were, of course, a number of affinities between works—here, I will focus on examples that relate to geographic realities, strong female perspectives, and Islamic ones.

Beginning in the Gallery of Modern Art’s (GOMA’s) soaring atrium space, an intriguing face-off was set up between the work of Indonesian artist Zico Albaiquni and Chinese star Qiu Zhijie. Albaiquni’s figurative paintings are an ‘exhibition field’, as the artist describes them (2). They are more than paintings or, rather, they implicate the viewer in a particular spatial construct. His paintings tend to present a collision of spaces that equate to a moment in which the history of painting is rewound in the present. He employs bright colour overlays, traditional Indonesian motifs, scenes inspired from daily life and iconography that speaks to the history of the Western tradition of painting. For the Bandung artist, painting is a language and an important lineage that makes space for revisions and reconsiderations of the embanked fights between figuration and abstraction; between Western, traditional, indigenous and religious concepts that ran through the history of Indonesian art (3).

Zico Albaiquni, various works, 2016-18, including (on the left) Negotiation of Understanding, 2016-17, pigment, oil and giclée on canvas; photo: Natasha Harth, The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9), Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; courtesy the artist.

Throughout his work, Albaiquni exploits the paradigm of painting as a hegemonic product of colonial influence, exploring what constitutes painting and the conditions of looking. Within the picture plane, all these references collide under the eye of viewers depicted in the painting that double our own experience. In Negotiation of Understanding (2016–2017) we look at the painting of a woman looking at a painting inside a distorted space made out of different architectural elements, that is reminiscent of an artist studio with unfinished works around the walls. There are many spaces of representation and material elements for painting that are depicted—brushes, pots of paint, etc. A condition of ‘being painting’, a material and representational picture plane, is further reinforced by an attention to the materiality of painting with the artist’s use of irregular canvases and the process of painting depicted within the field of the work.

Albaiquni is especially interested in exploring the contemporary condition of painting from the vantage of his local context yet engaged with a globalised art world—in Indonesia, painting is generally seen through the lens of lukisan (‘paint’, or ‘to paint’) but refers to the sacred practice made and mastered through rigorous rituals, a medium to communicate with the spiritual world. For Albaiquni, art is a transgenerational craft—it is a legacy that is always ‘being translated in the culture of those who live with it’, the artist says, with a belief that ‘every process of dialogue between cultures is an opportunity to enrich its vocabulary of a matter, and for my case it is painting’ (4).

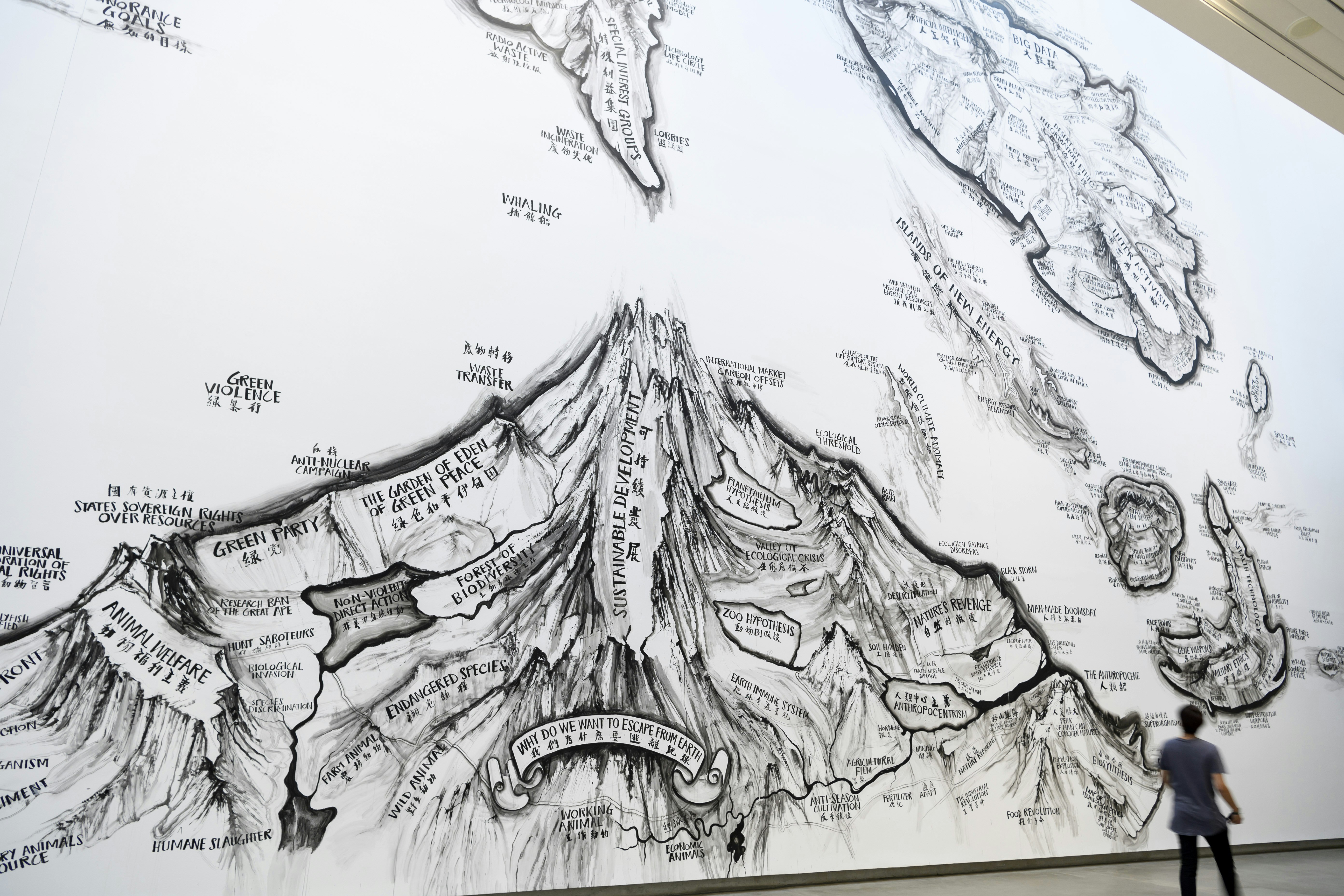

Qiu Zhijie, Map of Technological Ethics (installation view), 2018, synthetic polymer mural; commissioned for The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9); photo: Chloë Callistemon, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; courtesy the artist.

A collision of traditional and contemporary vocabularies is also at play in the monumental map by Qiu Zhijie in GOMA’s atrium. Facing Albaiquni’s paintings, Qiu’s work is an archipelago of islands of concepts, a kind of geographic dictionary that describes our contemporary global condition with humorous twists. Much like the world, this map is too big to be seen in one sweep, different regions appear: ‘Islands of Energy’, ‘Islands of Knowledge Power’, and other imaginary groupings that allude to dominant industries that are mainly technological or pharmaceutical ones. The imaginary islands the artist paints sound so real, tantalisingly suggesting the colonial force of capitalism as well as the violence implicit in the very exercise of mapping.

Given Qiu’s prominent and prolific activities as a curator in addition to being an artist (he was Chief Curator of the 9th Shanghai Biennale in 2012, for instance), perhaps this gigantic map is an exercise of curatorial awareness and reflection. As a survey, the APT creates a form of mapping of a region by the works and artists presented. For Kuala Lumpur-based art historian Simon Soon, exhibition-making as a mapping exercise within Asia can be dangerous because of the (sometimes) unintended flaws it implies: ‘An understanding of the world does not stem from the violent enterprise of mapping. It has less to do with the many disciplinary terrains, knowledge domains and geographic localities once can traverse and bind together through the stagecraft of the curatorial’ (5). Soon warns us of the dangers of mapping when undertaken by a Western culture because of the cultural projections it implies and its complexities, persistent paradigms that are difficult to surpass even when conditions are united in curatorial work. This is what the work of Qiu embodies, not only on the level of the metaphor, but also because he has been criticised as an artist and curator who embodies a kind of ‘Chinese ‘cliché’. For Chinese art critic Wang Nanming, Qiu’s work has attracted international success in the 1990s because it appeals to Western sensibilities (even with demonstrated good intentions by Western curators) (6). Here this can be seen with the English translation, networked drawing reminiscing of conceptual and the dominance of the visual effect of the traditional Chinese ink drawing. For Wang, the issue is that, in turn, a Western sensibility has shaped the reception of Chinese art and its development during the boom of the Chinese art market and the biennale circuits later in the 1990s. Therefore, Wang distinguishes Chinese clichés—western projections of Chinese stereotypes—from problematics that are works that reflect upon and criticise pertinent issues within Chinese society as a tool to understand Chinese contemporary art (7).

Janet Fieldhouse Kalau Lawgaw, various works with buff raku trachyte, red midfire terra, southern ice, jute twine, coconut leaf and fibre, raffia and metal; installed as part of Women’s Wealth at The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9); photo: Natasha Harth, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; courtesy the artist.

Works that reflect upon and criticise pertinent issues in the region were at the centre of APT9’s success in resisting colonising forces of the curatorial, starting with a plurality of curatorial voices and a refusal of labelled sub-themes in the exhibition that would dictate associations. Strong connections were evident between the works themselves in the exhibition display, and the fewer number of artists in this edition made for a slower pace, more space and seemingly greater autonomy given to artists to fill galleries.

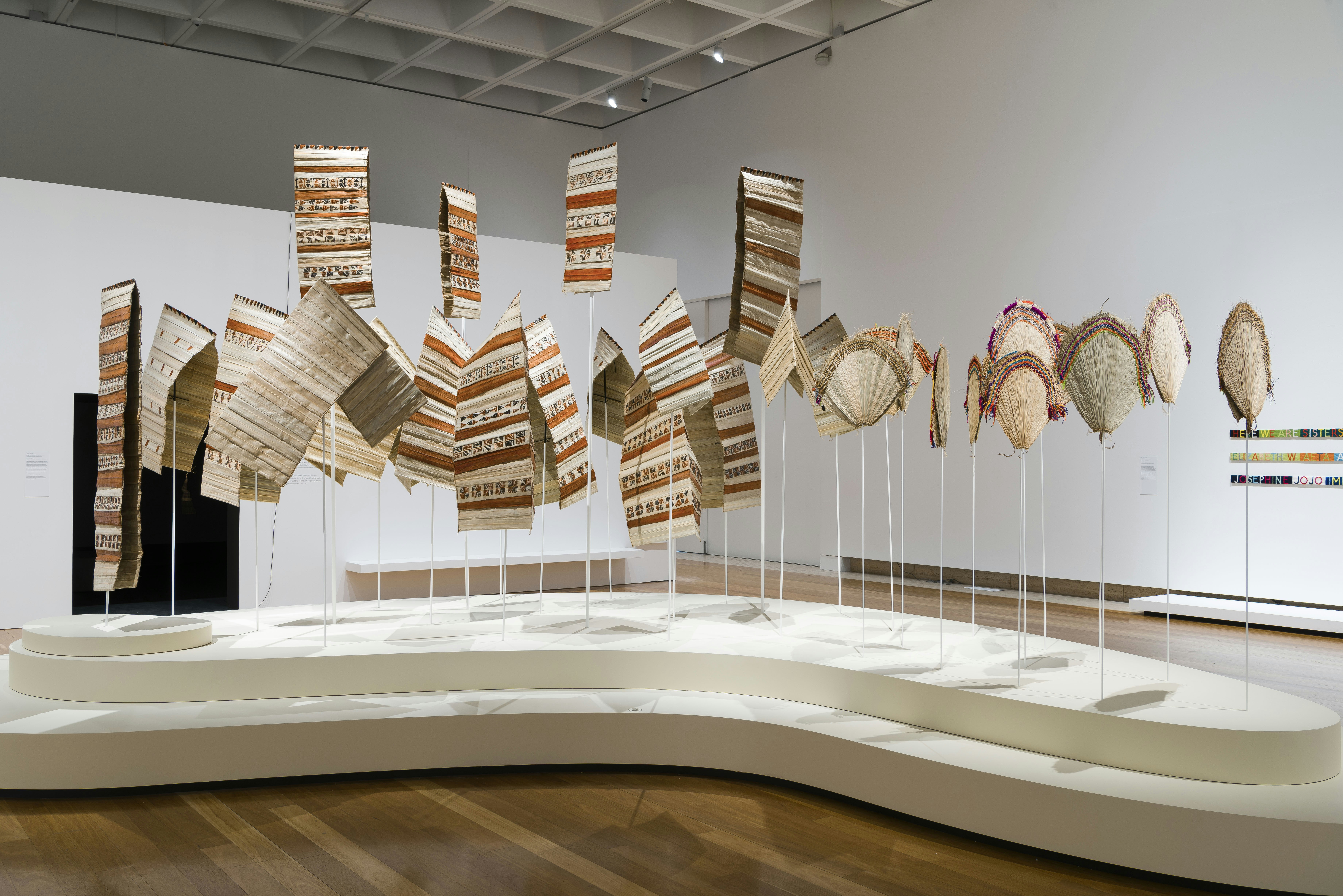

This year’s APT addressed conflicting modernities and geographic realities with a particular attention to women’s perspectives on political subjects. Outstanding works by numerous female artists enriched each and others’ concerns and practices. Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner’s grabbing spoken-word performance during the opening weekend gave presence to the artist’s experience with the Marshallese jaki-ed weaving circle, memorably signalling the importance of Islander culture, of family heritage, women-to-women transmission and authority. Similarly, the Bougainville/Solomon Island Women’s Wealth weaving project underscored the impact of collaborative crafts in communities as well as ecological and political concerns. For APT9 co-curator Reuben Keehan, the focus on women artists is something that emerged from the Women’s Wealth project, in the process of developing the exhibition. This project was one of the early landmark of the triennial, demanding a longer timeframe, it was developed first (8).

Concerns with women’s health, rights and practices were not the only focus for female identifying artists in the Triennale, of course. This is echoed by the presence of impressive textile works, such as Jakkai Siributr’s installation on the ground floor at GOMA that included his mother’s dresses, with hand-stitched embroideries of scenes of personal life from his mother’s diaries and scenes of political life and persecution in Thailand. These latter scenes are made with white threads, that gives the impression of ghosts always being present in the background, enmeshed with the family history. Hanging tapestries also paid homage to women in his family who donated clothes as material for his work. Siributr’s installation was bookended by Aisha Khalid’s colossal Persian-carpets inspired Water has never feared the fire (2018), hung at the entrance of the same gallery alongside Dunedin-born and based artist Kushana Bush‘s paintings that are influenced by Indo-Persian miniatures among many other styles. At first glance, the work appears to be embroidered; it reveals itself as the viewer progresses with its back showing thousands of nails pointed towards us in the air. This arrangement was amplified by the juxtaposition of Latai Taumoepeau’s photographs, from her durational performance Dark Continent (2015) commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art for its 48HR Incident program, in which the artist sprays herself brown, that speaks to the many layers of cultural projections upon the body.

Tuhu by artists of the Nakas, Nakaripa, Hakö and Naboin clans; Biruko by artists of the Barapang clan, Autonomous Region of Bougainville; installed as part of Women’s Wealth at The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9); photo: Natasha Harth, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; courtesy the artist.

Racial, body and sexual politics were particularly visible in the upstairs galleries with an installation of Naiza Khan’s metallic garments reminiscent of chastity belts and corsets. The work of Aisha Khalid and Naiza Khan, as well as Ali Kazim and other artists, build an important contingent of artists from Pakistan that hasn’t been represented as predominantly in past editions of the APT, creating a strong dialogue with other artists from South Asia in this edition, and an attention to crafts, themes and concerns from a Muslim community that is another subtheme present more widely in APT9. Public talks in the Triennial’s opening week stressed the difficulties of mobility and exchange in the region as well as raised the crucial question of hierarchies in the region’s cultural projections, asking who dictates South-to-South networks. For Naiza Khan, it is important for artists to go beyond official lines, to create parallel networks and uncomfortable positions for hijacking and reclaiming culture (9). Dhaka-based artist Munem Wasif further explained that ‘relationships’—at least within his community and younger artists—are perhaps more important than his own work, which further supports the social and transgenerational threads in the exhibition, and the approach of other artists such as the aforementioned Albaiquni.

Naiza Khan, various works from the Heavenly Ornament series, 2007-2017, galvanised steel, feathers, leather, fabric and zips; photo: Joe Ruckli, The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9), Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2018; courtesy the artist.

From the position of Brisbane, the APT provides a platform for interpreting various forms of cultural production, both material and immaterial. As a proposition generated by QAGOMA’s team of curators, it addresses the Australian imagination, explores geographic and political realities in relation to artistic imaginaries rather than being detached from it. This aspect of the Triennial allows for a plurality of positions and can be seen through current topics such as feminism and religion. Through time, the APT teaches us a practice of looking that acknowledges simultaneous modernities, connected histories, and shared concerns in the region. A testimony to this practice is the inaugural Beaut, or the Brisbane and Elsewhere Art Untriennial, an artist-run festival that connected spaces and artists of the Asia Pacific region in the last week of the APT (26 April – 5 May 2019) with projects at Outer Space, Wreckers Artspace, Kuiper Projects, The Walls and more. The meeting between the APT9 and its public, and the conversations that emerges from this undertaking, will set up some frames for the next edition, as co-curator Reuben Keehan insisted at the end of our conversation. Beaut is an alternative to the institutional proposition rather than an action against it. Hopefully, Beaut 2019 will also be the first in a series of many editions or other offshoots. The two undertakings are equally important as they strive towards the same aim.

Notes

(1) Mary Cappello, ‘Heir to Ambiguity’, Interim 26:1-2 (2008) 259.

(2) Comment by the artist during the APT9 opening weekend program, Discussion: Intergenerational Influences hosted by Reuben Keehan, with Kawayan de Guia, Yuko Mohri, Zico Albaiquni, QAGOMA, 25 November 2018.

(3) Zico Albaiquni traces these fights to fights between the progressive Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB), where he studied, and the social realist Jogya school, which carried through to important art movement in Indonesia through the 1970s with the New Art Movement (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru – GSRB) and 1990s with ‘Reformasi’ artists of the era including Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani, Tisna Sanjaya, Eddie Hara, Heri Dono, Mella Jaarsma, Semsar Siahaan). Unpublished artist interview with the author, 6 February 2019.

(4) Interview with the artist by the author, 6 February 2019.

(5) Simon Soon ‘Rethinking Curatorial Colonialism’ in Ute Meta Bauer and Brigitte Oetker (eds.), South East Asia: Spaces of the Curatorial (Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2016), 225.

(6) This is discussed in Ma Lin, ‘Chinese problematics in contemporary art and exhibition making’ in Sophia Yadong Hao, Edgar Schmitz (eds.), Hubs and fictions on current art and imported remoteness (Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2016), 67. It references Wang Nanming, The Honour of Postcolonialism (2012) and The Rise of Critical Art-Chinese Problem Situation and Theories of Liberal Society (2009).

(7) Ibid.

(8) Interview with Reuben Keehan by the author, 11 February 2019.

(9) Comment by the artist during the opening weekend Discussion: South Asia hosted by Tarun Nagesh, with Munem Wasif, Naiza Khan and Suman Gopinath, QGoMA, 25 November 2018.

About the contributor

Anabelle Lacroix is a curator and writer.