History’s long shadow: the rehabilitation of Japanese–Australian relations through art

Mikala Tai

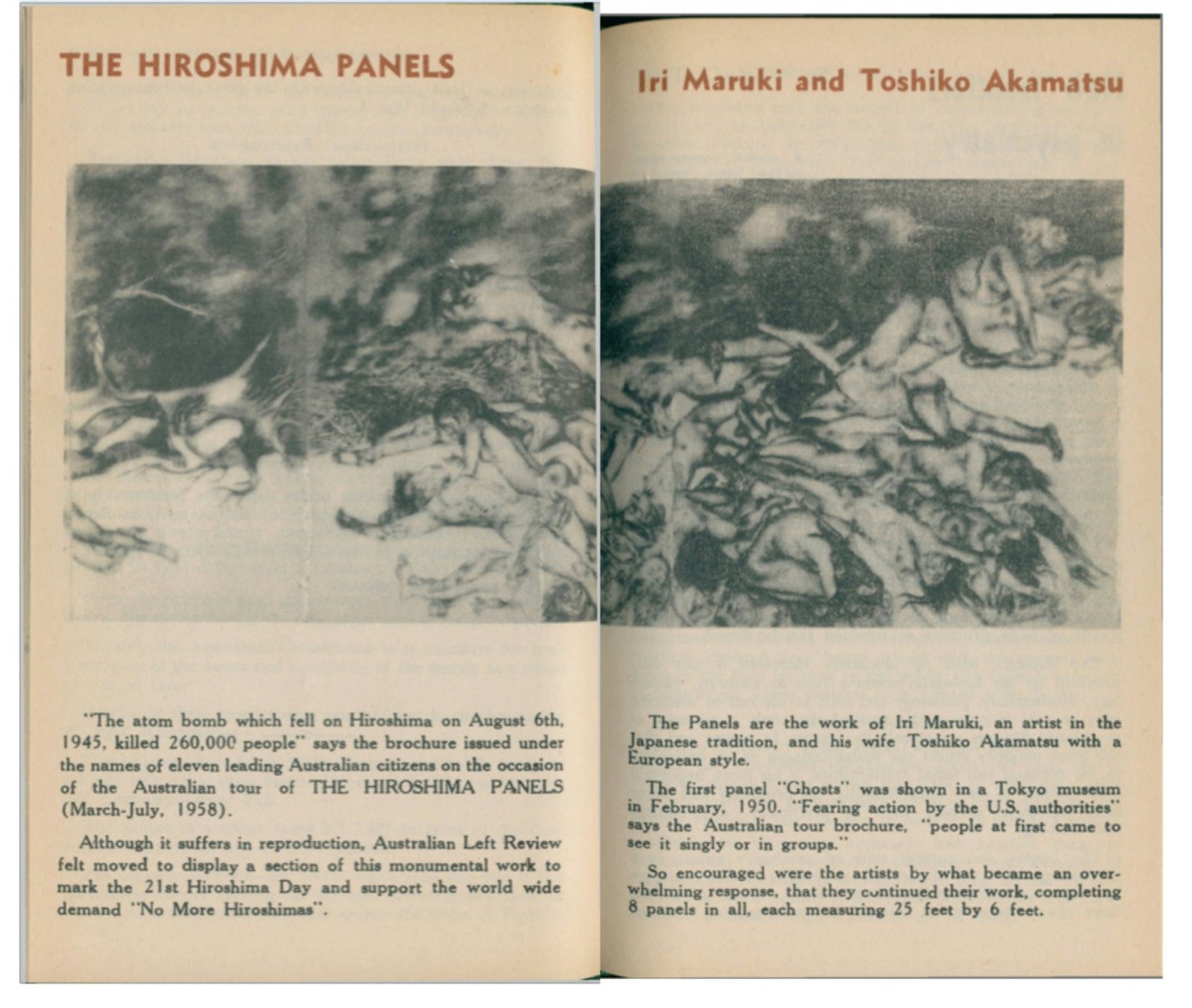

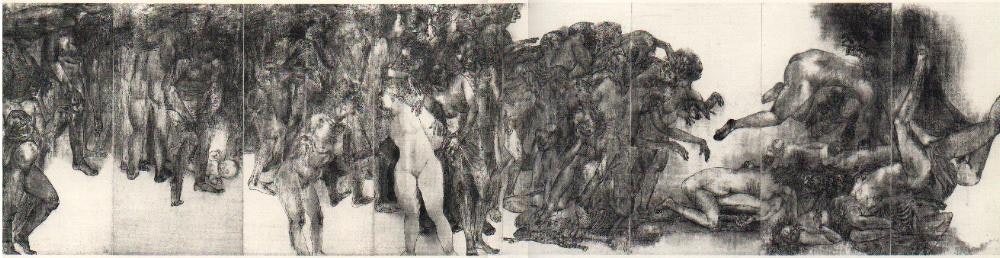

Iri Muraki and Toshi Maruki, Fire (detail), 1950, panel #2 from The Hiroshima Panels, 180 x 720 cm; courtesy the Maruki Gallery for The Hiroshima Panels Foundation.

A note to the reader:

In early 2017, I lost my grandmother. Linda Tai lived through historical upheaval and was witness to the most significant period of Chinese modern history. Born in 1921 in Shanghai, she experienced civil war, Japanese occupation and, when the Red Guard destroyed her family home, she married my Cantonese pilot grandfather and escaped to Hong Kong. And while she made a new life and learnt new languages the horrors of her early adulthood never left her. We rarely spoke about this. In fact, we made a concerted effort to never talk about many things. But when we did they were still very raw and very real.

Her memories of the Japanese occupation were visceral and bloody. Until her death Japan remained a source of great pain. My growing fascination with the country and its people, art and culture remained unspoken. This lived experience had forever changed her and the mere thought of going to a Japanese restaurant was incomprehensible. I ate ramen with friends but never with her. When she passed away I, somewhat guiltily, travelled to Japan for the first time in the months after her death. So did other members of my family. The burden of Linda’s experience was lifted and, through the passing of time and the erasure of memory, we were able to form our own relationships with a country so very different from the one she remembered.

This experience led me to consider how Australia sought to rebuild a relationship with Japan after WWII. I was interested in how Australia navigated this reengagement with sensitivity to the profoundly painful lived experience of so many. This article is an early summation of my research and leans heavily on Simon Fisher’s honours thesis An Era of Two Images: Japan in the Eyes of the Australian Public 1950-1960, expanding the discussion of Australian presentations of the Hiroshima Panels and the exhibition ‘Contemporary Japanese Art’. A version of this article was presented at the AAANZ Conference (Art Association of Australia and New Zealand) held at RMIT University, Melbourne, 5–7 December 2018.

There are moments in life when absolutes are compelling. When the howling laceration of lived experience determines an opinion so staunch and so concrete it is unfathomable to consider anything else. At the end of WWII, following Japan’s earlier military attacks, Australia was fundamentally scarred. In Japan’s attempt to conquer the Pacific, its forces raided Darwin, Broome and Townsville killing over 200 Australian citizens. Australia lost 34,376 soldiers in the war and 8,031 had perished in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps (1). At this moment it was improbable, and perhaps even outrageous, to consider that Japan could ever be an ally in the future. The wounds were too raw, too close and too widespread.

These sentiments quickly translated into policy with the Federal Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, speaking in absolutes in 1948:

While I remain Minister for Immigration, no Japanese will be permitted to enter this country. They cannot come as the wives of Australian servicemen … nor as businessmen to buy from or sell to us … The feelings of the mothers and wives of the Australian victims of Japanese savagery are more important than any trade or other material advantage (2).

The possibility for trade, let alone friendship, was seemingly impossible. However, just nine years later Australia became the first nation to open its doors to trade with Japan after WWII when the Agreement on Commerce between the Commonwealth of Australia and Japan was originally signed on 6 July 1957. This shift, determined by economic opportunity and bilateral relations, required public opinion to significantly shift and for Australia to recast hostility into hospitably. This change of attitude saw increasing efforts to link the two countries economically, foster political and business ties and, most importantly for this discussion, embark on cultural and personal exchange. The first major cultural endeavour undertaken bilaterally by both the Australian and the Japanese governments were two exhibitions that toured Australia in 1958 that reformed Japan in the eyes of the Australian public and illustrated that, as William Macmahon Ball, the Australian Minister to Japan noted in 1960: ‘[Japan] is certainly no longer a militarist or expansionist nation … On all counts it would seem good sense for Australia to work as closely as possible with Japan’ (3).

Front cover of the pamphlet toy manufacturers and retailers produced to protest Japanese toy imports. It reads ‘Ban Jap Toys: Have you Forgotten?’, The Courier Mail, 31 August, 1951.

The shift in public opinion was integral to Australia’s economic future and its increasing engagement with the wider Asia region. Between the end of the war and 1958 there were several events that laid the foundations for the rebirth of Australian–Japanese relations: the Japan Peace Treaty 1951–52 was signed which paved the way for Australia to inch towards engagement with Japan; the arrival of Japan’s first post-war ambassador to Australia; and a 1954 Japanese baseball tour show that received positive attention being two of them. But still the antagonistic image of Japan remained strong with fear of Japanese immigration to Australia continuing to manifest in the White Australia Policy under the guise of preserving ‘cultural unity’, a 1951 boycott of Japanese toys by Australian retailers that had a significant pamphlet campaign that co-opted an image of emaciated POWs alongside the evocative ‘Have you forgotten? Ban Jap Toys’ (4). However, the graphic nature of this campaign ignited public debate that appeared across major publications such as The Advertiser and The Argus to The Barrier Miner which rejected such clear propaganda and labelled it a ‘hate campaign’, indicating that the absolutes that Calwell drew on in 1948 were beginning to wane (5).

By the mid 1950s, public discussion about Australia’s engagement with Japan was developing. As researcher Simon Fisher pinpointed with two telling quotes from 1954—the first a statement by then Prime Minister Robert Menzies: ‘The happiness of the future depends upon the future and not nursing the bitterness of the past’; and the second, from The Argus: ‘What ARE we going to do about Japan, and the Japanese? Are we going to hate them forever, or are we going to receive them back into our company as civilised people?’ (6). Tied to this sentiment was the active construction of Japan as a modern and civilised society akin to Australia that too was emerging from the horrors of war. In 1957 the Agreement on Commerce Between The Commonwealth of Australia and Japan was signed and this accordance became the foundation of economic, political and social engagement between the two countries.

A year later, in 1958, two significant exhibitions of contemporary Japanese art were presented in state galleries around Australia that sought to move beyond wartime animosity and develop empathy and understanding within the Australian public towards Japan. The Hiroshima Panels: Iri Maruki and Toshiko Akamatsu and Contemporary Japanese Art visited the state galleries of Queensland, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and New South Wales and were supported by both the Australian and Japanese governments. These exhibitions were the first large-scale presentations of contemporary Japanese art in major state institutions.

Iri Muraki and Toshiko Akamatsu, Ghosts, 1950, panel #1 from The Hiroshima Panels, 180 x 720 cm; courtesy the Maruki Gallery for The Hiroshima Panels Foundation.

The Hiroshima Panels presented a series of eight large-scale figurative drawings that depict the aftermath of the atomic bomb. The works are, like Picasso’s Guernica or Goya’s Horrors of War, raw and confronting. Human emotion is palpable as desperate searches for survivors are rendered amidst ruin and mass destruction. Iri Maruki (1901–1995) was born in Hiroshima and after the bombs he travelled, with his wife Toshiko Akamatsu (1912–2000), to search for relatives. In the decimated city they found themselves attempting to orient themselves amongst burnt buildings and charred remains with air thick with smoke that smelt like death. In took three years before they began to paint the panels and reflect on the weeks they spent in Hiroshima tending to those injured and ceremoniously farewelling the dead. The panels reflect not only the horror they personally witnessed in the aftermath but also the extensive research in the years that followed. In Australia, only eight panels were displayed as it took over thirty-two years (1950–1982) for fifteen large folding panels and their accompanying poems to be created.

Each work consists of eight hinged panels of an evolving scene. At almost six feet tall they are constructed in the style of a tradition byōbu screen that is almost 24 feet long. This style of screen’s literal translation is ‘to shield from wind’ and is often used as a room divider decorated with depictions of landscapes, traditionally a byōbu screen would depict a cherry blossom in full bloom or a cityscape but here the monumental landscape format becomes a memorial to the horror of the aftermath of Hiroshima in vivid, and almost life size, scale. The first panel the Maruki’s created is Ghosts (1950), an ashen nightmare of naked figures that seemingly drift in a perpetual state of purgatory. Even in death they are rendered as desperate, skeletal frames clutching at their faces and tangled together. The second panel, Fire (1950), is equally desperate capturing the moments after the explosion with vivid red that appears in every panel. The introduction of red conveys the ravenous fire that compounded the immediate devastation of the bombs. The bodies depicted in Fire appear in agony, pleading to the heavens and in utter desolation.

The works are, like Picasso’s Guernica or Goya’s Horrors of War, raw and confronting. Human emotion is palpable as desperate searches for survivors are rendered amidst ruin and mass destruction.

The panels consist of layered imagery, each collaboratively built-up by the artists to create a sense of multiplicity in the final image. Each figure was outlined by Toshiko in ink and chalk in keeping where her illustration practice and then Iri’s black and while sumi-e, or inkwash, was applied sinking into the paper and blurring the edges of the figures, erasing the clarity of Toshi’s work. This process was repeated continuously until the final image emerged (7). The final work hovers between Japanese and Western art historical traditions incorporating Japanese techniques and media but with figures rendered in more European style. The resulting work speaks to both traditions and is a compelling example of international contemporary art.

The 1958 touring Australian presentation of the Hiroshima Panels was the first time Australian sympathies for Japanese victims of the war were enacted in such prominent public spaces. The exhibition attracted attendance figures into the hundreds of thousands—impressive numbers for any exhibition in 2019, let alone 1958—with the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide reporting it to The Australian Women’s Weekly that it was its most well attended exhibition that year, prompting the gallery to extend its opening hours into evenings and 10,000 people seeing the show in just four days (8). In Sydney, the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ annual report defined the exhibition as one of its most ‘impressive and popular’ of the year, with the gallery having rearranged its schedule after previously passing on the exhibition (9). Journalists and art critics urged the public to see the exhibition and to learn from the lessons of the ‘horror of modern war’, while members of the public, in earnest and heartfelt letters to the editor, such as to The Age (pictured below), commended the exhibitions of the panels and their ‘horrifying lesson’ on the impacts of ‘vile war’ (10). When there were letters that questioned the exhibition, such as one to The Sydney Morning Herald that urged that Australians should never forget the atrocities and deaths at the hands of ‘the knights of Bushido’, they were quickly followed by a flurry of other letters that argued the panels were in fact ‘two artists' sincere warning to humanity’ (11).

The exhibition attracted attendance figures into the hundreds of thousands—impressive numbers for any exhibition in 2019, let alone 1958.

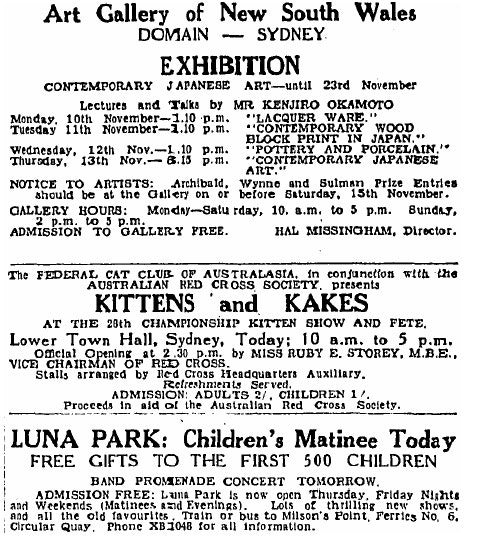

While The Hiroshima Panels: Iri Maruki and Toshiko Akamatsu was an exhibition forged on tight curatorial specifications, 1958 saw the presentation of Contemporary Japanese Art that began its tour from the Art Gallery of New South Wales with a much looser curatorial framework. Spearheaded by the Japanese Ambassador to Australia, Tadakatsu Suzuki, and funded by both the Australian and Japanese governments, this exhibition sought to illustrate the nuances and realities of contemporary Japanese life. While The Hiroshima Panels was clearly underpinned by political and historical references in search for empathy, Contemporary Japanese Art illustrated a more liberal and nuanced idea of Japan in its attempt to foster a new understanding of a ‘contemporary Japan’. In Suzuki’s opening remarks in the catalogue he stated his hope that the exhibition would encourage and enable Australians and Japanese to ‘more closely understand and appreciate one another’ (12). Supporting this was a series of public programs that featured Tokyo-based art critic Kenjiro Okamoto, who travelled with the exhibition delivering lectures of contemporary Japan and the countries long artistic history, in some ways a precursor to the work the Japan Foundation does today throughout Australia with its support of exhibitions and cultural education.

Art Gallery of New South Wales listing of Contemporary Japanese Art in The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 November 1958.

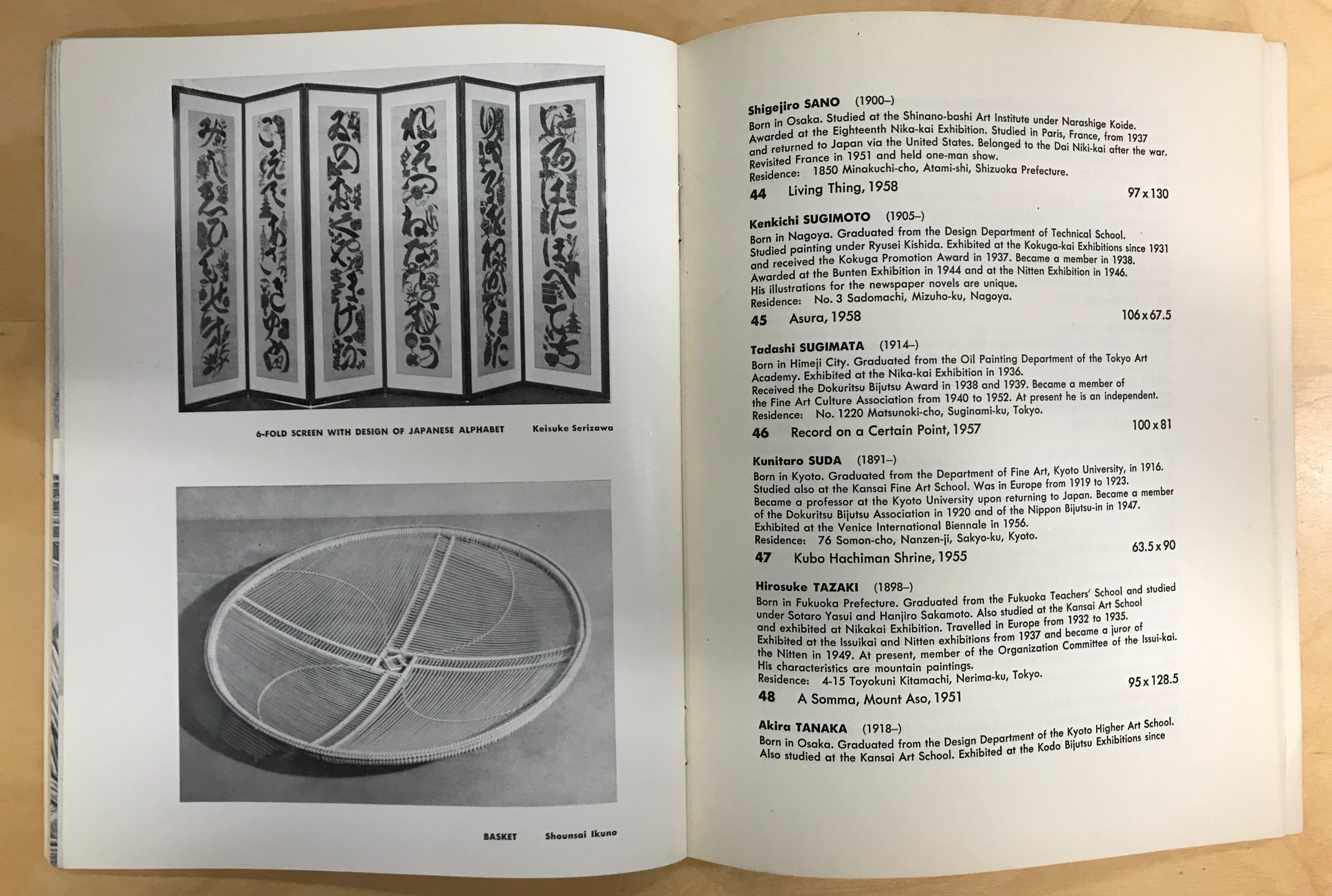

Contemporary Japanese Art opened at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in November of 1958 before traveling, in swift succession, to the National Gallery of Victoria, the National Gallery of South Australia, the Art Gallery of Western Australia and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in May 1959, before it toured to New Zealand. It was open for a little over a month at each venue, displaying the breadth of Japanese contemporary practice including paintings, prints and ceramics to bamboo crafts, textiles and lacquerware.

The works presented in Contemporary Japanese Art were a significant, and perhaps deliberate, counterpoint to The Hiroshima Panels, largely seeking to illustrate the craftsmanship of Japanese artists and artisans and convey the nation’s deep cultural values and traditions. The work is indicative of a culture that appreciates the arts—a sentiment at odds with the lingering image of a warring militarist nation. From the delicate bamboo craft of Shounsai Ikung to the thoroughly contemporary metal lacquer octagonal box of Tadashi Saji, the works exhibited were exemplary examples of Japanese art and design. Intriguingly, a work by Iri Maruki was also included, a landscape at the more conservative scale of 96 x 126.5 cm that, while not illustrated in the catalogue, is described as expressing, ‘a new tendency of Japanese-style painting with the traditional description technique of the old Japanese picture-stories’ (13). It is clear that at the end of the 1950s Japan clearly identified the work of Maruki’s as a compelling tool for cultural diplomacy.

The response to the exhibition again played out in the papers. There were conflicting reports as Australian critics grappled with the mediums and considerations of Japanese contemporary art, yet the curatorial concept and the ability to learn more about Japan was generally greeted positively (14). In letter correspondence with Prime Minister Menzies in 1959, the director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hal Missingham, commented that the state galleries all agreed that the exhibition had been important and of critical value to the Australian public on both ‘its artistic level and on the undoubted influence it could have in fostering of a more amicable relationship between Japan and Australia’ (15).

By 1958, public opinion dismantled the absolute that Calwell committed Australia to just ten years prior. Through a decade of sensitive economic and political manoeuvres and large-scale cultural investment Japan was recast in the eye of the Australian public. The role of cultural diplomacy in the rebuilding of Australia’s relationship with Japan was clear. However, it is what has happened to these artworks that is of further intrigue.

By the close of Contemporary Japanese Art in 1959, New South Wales public funds secured several prints for the Art Gallery of New South Wales: a series of three works titled Thunder No. 4 (1958) by Seiji (Masaji) Yoshida; Temptation (1958) and Monument (1958) by Takumi Shinagawa; and Record of that Day (1958) by Toshi Yoshida. While all remain in the collection today, only Yoshida’s Thunder No.4 has been displayed in the decades since as part of the exhibition Japanese Prints of the 20th Century in 1990. Their political potency has long faded in a thoroughly respectable collection of Japanese prints.

The Hiroshima Panels had a long diplomatic mission even before they were exhibited in Australia. They had travelled to Eastern and Western Europe in 1953, and in 1956 their world tour first went to the USSR, China, North Korea, West Germany and onto other cities in Western Europe, before South Africa and then Australia and New Zealand. This tour of the 1950s saw the panels largely out of Japan for a decade. The panels however, did not tour to the United States until 1970 where they were met with a public reception similar to that in Australia: a few outraged letters to the editor, but largely words softened by time and distance that sought to recognise the horror and destruction of war (16). They have since returned to the U.S. three times, once in 1988, again in 1995—the same year they were nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize—and most recently in 2015. By the end of the 1970s the panels had toured to almost thirty countries on, as John Dower and John Junkerman note, ‘both sides of the cold war’ (17). But today, despite the inclusion of Fire in Okwei Enwezor, Ulrich Wilmes and Katy Siegel’s mammoth 2017 exhibition Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945-1865 at Munich’s Haus de Kunst, The Hiroshima Panels remain relatively unknown.

Since 1967, the panels–once so instrumental to the Japanese government in rebuilding the nation’s international image—have been housed, in a gallery an hour drive from central Tokyo. The Marukis established and funded the Maruki Gallery in the small town of Higashi-Matsuyama for all but one panel, and remained committed to maintaining the gallery until their deaths in 1995 and 2000. The fifteenth (and final) panel, Nagasaki (1982), is on permanent display in the Nagasaki International Cultural Hall. Since 2017, the Maruki Gallery and The Hiroshima Panels Foundation has been petitioning for donations; the galleries are neglected and well below museum standards, and no home for works of such historical importance. The panels themselves are in varying states of damage and their future is reliant on private funds for conservation. The Japanese government, who once held The Hiroshima Panels at such esteem, is not currently playing an active role in securing their future.

The diminished global understanding and appreciation of The Hiroshima Panels is evidence of the complexities and remaining sensitivities of post-war international relations with Japan. The important role that the panels played for the rehabilitation of Japan’s global image serve as a reminder of a fraught period of the nation’s history. The panel’s current relative invisibility is a signal that all is not resolved, and that the potent and long-standing lacerations of WWII continue to cast long shadows.

Notes

(1) T. B. Millar, Australia in Peace and War: External Relations since 1788 (Canberra: ANU Press, 1991), 120.

(2) Cited in Alan Rix, Alan, Coming to Terms: The Politics of Australia’s Trade with Japan 1945-57 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1986), 180.

(3) Cited in Alan Watt, Alan, The Evolution of Australian Foreign Policy 1938-1965 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 200.

(4)The Returned Sailors, Soldiers and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia, Thirty Seventh Annual Report and Balance Sheet (P.P, 1952), 30.

(5) The Advertiser, 30 August 1951; The Advertiser, 1 September 1951; The Advertiser, 6 September 1951; The Advertiser, 8 September 1951.

(6) As cited by Simon Fisher in An Era of Two Images: Japan in the Eyes of the Australian Public 1950-1960. A honours History thesis submitted to The University of Sydney, October 2011, 38.

(7) Claire Voon, ‘The Historic Panels that Exposed the Hell of Hiroshima’ in Hyperallergic, 30 November 2015.

(8) The Australian Women’s Weekly, 9 July 1958.

(9) Report of the Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales for 1958 (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1959).

(10) The Australian Women’s Weekly, 9 July 1958; The Age, 10 April 1958; The Daily Telegraph, 3 July 1958; The Bulletin, 16 April 1958.

(11) The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 July 1958 and 25 July 1958.

(12) Tadakatsu Suzuki, ‘Forward’ in Contemporary Japanese Art, (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1958), unpaginated.

(13) ‘Iru Maruki’ in Contemporary Japanese Art, unpaginated.

(14) The Daily Mirror, 6 November 1958; The Age, 9 December 1958; The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 November 1958; The Bulletin, 19 November 1958.

(15) Letter from Art Gallery of NSW Director Hal Missingham to Prime Minister Menzies 30th October 1959, A463, 1956/1176, NAA.

(16) See John W. Dower and John Junkerman, The Hiroshima Murals: The Art of Iri Maruki and Toshi Maruki. (Tokyo: Kondansha International, 1985), 19.

(17) Ibid.

About the contributor

Mikala Tai was the director of 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney from 2015 — 2020.