Melancholy and desire: understanding the power of queer metaphor in the art of Moses Tan

Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung

Moses Tan, Slow Steps (still), 2019, single-channel video; courtesy the artist.

I. Melancholy

What does it mean to chase the night? At clubs and warehouses, dance floors throb with bodies that swerve and jostle as if overcome by some spiritual trance. If you listen closely, you might hear the hum of voices bubbling beneath the doof doof beat; the truth is talking without kissing is gauche, so it feels better for limbs to concede defeat and submit to the world of party.

At times, there are moments on the dance floor which afford rave-goers a much-needed reprieve: heavy beats dissolve to make way for lighter, more placid melodies. Long, sustained notes from what could be an otherworldly cello emerge to seize sonic control from overzealous drums which fade, but never fully disappear. There is a push and pull until the music softens; a new song emerges, held together by a faint pulse in the background. Once rapid and atonal, the dance breaks into an airy Donna Summer serenade, cooing and announcing itself from all around.

For me, these are moments saturated with a particular kind of melancholy. Here in the relative silence, we become aware that the party is always working towards an inevitable climax. At this inlet, we are confronted by the sadness of finality—the end. The dull drum begins to signal its return and Donna’s grip weakens. We feel the crescendo building for round two. Melancholy has found us, but we do not let it in. So, as the bass returns swinging, we slide into another escape. That original intensity is back and our reprieve is gone. Melancholy is here; but for now, we do not care.

When music changes, bodies are put on notice. A shift in timbre acts as a glitch that warps us back into the present, pulling us out from the otherwise introspective act of techno dancing. Hunched backs return upright. Fist pumps ease into more fluid gestures. To watch others at this point in the night (or day) is to witness the metallic sheen of dewy skin: of eyes rolling back and tired jaws clenched tighter than hands which clutch bouquets of sweaty hair as bodies continue to sway.

Chasing the night requires of us to confront this melancholy at different intervals. It is a sobering moment of truth when we feel that either ourselves or the party must end. And yet, when melancholy arrives we feel compelled to deny its force. This relationship between the recognition and denial of melancholy speaks to ways queerness is conceived in societies that seek to silence it. When the rave becomes metaphor, one begins to appreciate the tension that Singaporean artist Moses Tan seeks to address. That queerness, a once vibrant part of Singapore’s cultural fabric, exists as a kind of melancholy that plagues the Singaporean ego; denied whenever it is exhumed but nevertheless an omnipresent and critical part of society.

Moses Tan, Slow Steps (still), 2019, single-channel video; courtesy the artist.

Melancholy is here; but for now, we do not care... It is a sobering moment of truth when we feel that either ourselves or the party must end.

I am transported to these slower moments at the rave when I see Moses’ video installation Slow Steps (2019) for the first time at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. The work is a free-standing wooden structure obscured at eye-level by a perimeter of ruched calico that we must part to enter. Inside lies a video that shows two implicitly queer individuals who never meet. While neither character faces the camera, we deduce they inhabit parallel lives in the same Singaporean mise-en-scène. From a domestic kitchen to a multi-storey carpark, Slow Steps cross cuts so that both protagonists feel at once together but isolated. We stare as they sway front and back, side to side. After a while, it feels as though we are in that party lull together, anticipating the next intense beat. Both take turns dancing with us to a remixed version of Leonard Cohen’s Boogie Street (2001): hips sway to and fro and we cannot help but code their rhythm as seductive; miniskirts and singlets perhaps marking some kind of latent, sexual intent. Yet, as these two figures never meet our gaze, Moses relegates us to the role of a voyeur—building tension he has no plans on releasing. Without eye contact our assumptions of their latent sexuality are left suspended and never confirmed. A billowing haze of smoke enters which gradually obscures the scenery. Our anticipation becomes confusion and ends with dejection. Eventually, the characters disappear.

Moses Tan, Slow Steps (installation view), 2019, fabric, wood, single-channel video and audio; photo: Document Photography, By All Estimates, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, April - May 2019; courtesy the artist.

Slow Steps is a work which speaks to the role melancholy has in both informing and erasing queerness. Melancholy ascends from imminence and unresolved anticipation: of imagining the two faces in the video to reveal themselves or how their dance will shift gears, but in the end having none of these illusions realised. When I speak with Moses, he tells me that Slow Steps queries Singapore’s historical attraction to and cultural erasure of queerness. Like the melancholy which affronts bodies on the dance floor, queerness confronts and disrupts the dominant discourse in Singaporean society. But it too is a paradoxical reckoning. Moses seems to suggest that where queerness proclaims space, Singapore is deft only at exercising a severe dichotomy: to either objectify or erase. Yet, it appears one inevitably leads to the other, with the Singaporean ego remaining fixed within that emptiness Slow Steps leaves us with.

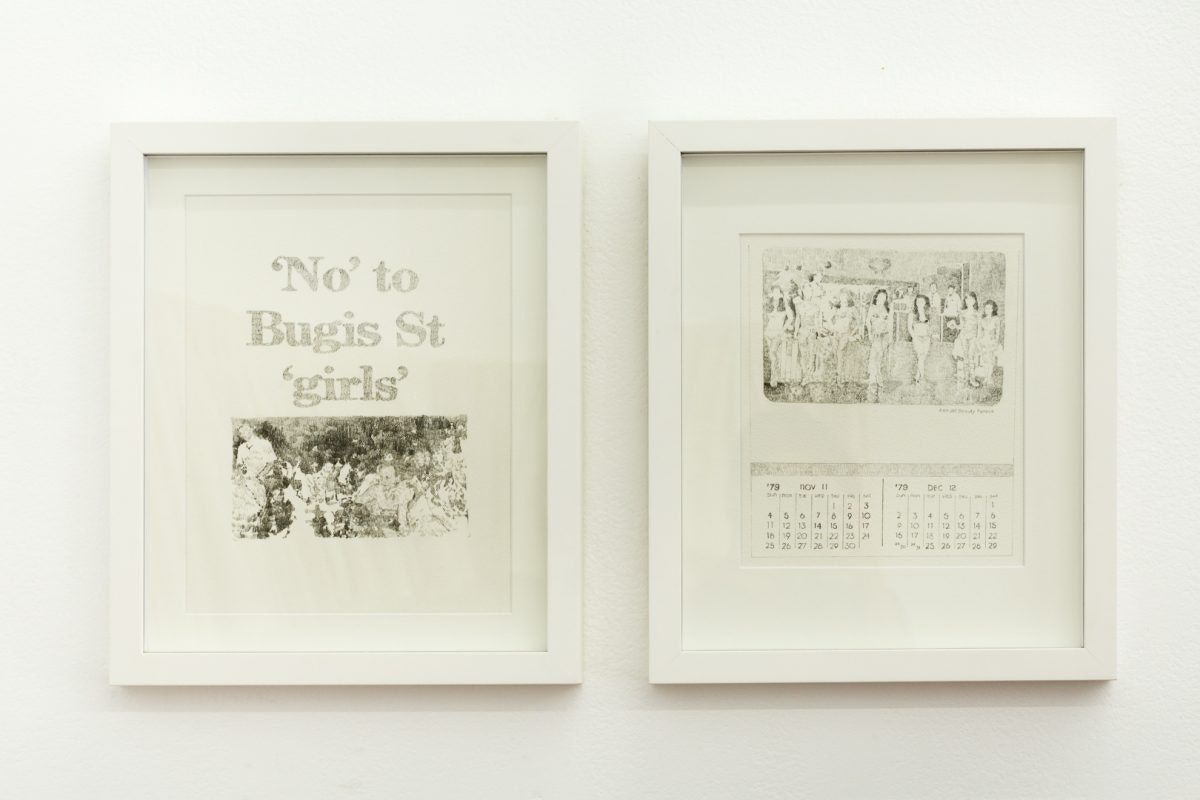

From the 1950s to the 1980s Singapore was home to a vibrant scene of queer inhabitance. The epicentre was Bugis Street, famed for its transgender community who were of global renown to businessmen, the Navy and cross-continental tourists. Yet, despite the ‘outsized notoriety and its objectification as touristic spectacle,’ Bugis Street bore also the brunt of social abjection (1). It was a street spoken of and delineated in Mandarin as ‘non-human’—a verbal flourish which justified the various acts of dehumanisation inflicted by mainstream Singapore onto Bugis Street’s transgender inhabitants (2). This is a history little spoken of in the contemporary cultural curriculum of Singapore. Today, the truth of Bugis Street as a repository of queer history is buried beneath the artificial capitalist narrative Singapore’s government tries to sell: that the cultural worth of Bugis Street lies in its monolithic, fast-fashion ridden yet deeply asexual shopping mall. Bugis Street is designed so that both tourists and Singaporeans alike forget the queer geography they stand on: flashing lights and endless advertisements beckoning a different kind of indulgence here than was experienced around the middle of last century.

In part, rapid gentrification is blamed for the erasure of queerness from Bugis Street and Singapore’s cultural narrative. With the erection of new buildings and Burger King-style transformation, the social blueprint has been overridden. Queerness and the camp spectacle which once defined Singapore to the world has moved from the cosmopolitan to the underground. Aaron K.H. Ho argues that there has been a ‘constant erasure and rewriting of Singapore’s queer history’ since the 1980s, which has ultimately led to the nation suppressing its own queerness (3). Moses seeks to memorialise and bring to the forefront of the Singaporean consciousness these hidden strands of their shared history, a form of creative resistance that seeks to address how the discursive memory of Singapore, and in particular its recesses of queerness, are frozen in this state of denial and melancholy.

Moses Tan, A Eulogy to Boogie Street (installation view), 2016-2019 (ongoing), graphite on paper; photo: Document Photography, By All Estimates, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney; courtesy the artist.

Cultural theorist Laurence Leong Wai Teng argues that the reason for this erasure lies in the illusory mantra and ‘cultural alibi [that] we Asians are conservative’, often employed by Singaporean politicians (4). In more pragmatic terms, through entrenching the rhetoric that Asian society is inherently conservative, (and thus heterosexual) into dominant cultural discourse, Singapore’s queer stories are rightfully silenced. Yet, the conceit and naivety of this cultural reasoning is that denouncements of queerness do not eliminate its existence. Indeed, to reason Asian society as conservative is to deny an inevitable truth that sexuality is slippery. Perhaps then, Singapore’s melancholy arises from a refusal to believe.

II. Desire

It’s a Thursday night when I meet Moses at the Grand Concourse at Sydney’s Central Station. Rain flitters down and my shoes squeak as I walk into the building. This is the oldest part of the train station: sandstone walls and iron buttresses, glazed windows where light peeks in at obtuse angles, filtering down onto polished floors. The old-world roar of steam trains becomes infantilised by the high-pitched beeps of Opal cards and I am reminded that this colonial city is modernising.

As a part of my tourist program, I am taking Moses gay cruising around Sydney’s CBD. Cruising is the practice of men meeting in public locations with the aim of having anonymous sex with other men (5). It is a practice alive and active in many parts of the world, with men meeting in public parks, toilets, swimming pools and other rendezvous locales. There is a bathroom inside the train station I want Moses to see, and while the aim of the evening is not to ‘get off’ per se, I thought it might be (artistically) appropriate to show him a few of these sites.

Slow Steps forms a part of Moses’ larger body of work Memorial for Boogie Street (2017) developed in residency at the Santa Fe Art Institute. In his work Cruising Cruiser (2017), Tan invites us to enter a makeshift lamp to don goggles that thrust us into a VR cruising site, caught in ‘a state of searching’ that never resolves in actual climax (6). Cruising Cruiser references bathrooms on Bugis Street that were known as designated cruising zones, with Moses’ virtual reconstruction acting as a kind of shrine or tomb to a place of desire and ecstasy that is no longer.

To reason Asian society as conservative is to deny an inevitable truth that sexuality is slippery. Perhaps then, Singapore’s melancholy arises from a refusal to believe.

Moses Tan, The Oral History of Boogie Street (installation view), 2019, fabric, 8-single-channel audio; photo: Document Photography, By All Estimates, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney; courtesy the artist.

Within the context of public bathrooms, those who enter looking for sexual partners actively subvert dominant codes of masculinity taught to regulate intra-male behaviour. So far as the urinal is concerned, there are performative rules which govern social interaction. Eyes down, or up, but most importantly don’t wander—don’t stand too close, speak or linger. Men follow these rules under the primary guise of etiquette—to hold discomfort at a distance and to minimise its metastasis; to desexualise the act of pulling out one’s bits; and, most importantly, to neuter any hint of sexual suggestion or intimacy amongst strangers. Cruising thrives and survives on the complete denouncement of these rules. Eyes dart at the urinal to find others with the same desires. When gazes are locked, gesture at your crotch and let them move closer. Stand together and reach down— grab and pull, but release if another walks in. If they’re kindred let them join, or not, but persevere until you crave more or something different. If the mood is right, take yourself and your newfound lover into the last cubicle.

It is difficult to frame or place into words the physical and emotional gestures which constitute the act of cruising. Public sex remains attached to a particular kind of stigma: of exhibitionism and the grotesque, a perversion that is inherently against the public interest. However, notions of shame and disgust imposed by those outside onto the cruising community is at odds with the rudimentary desire for sexual release that propels individuals to participate in this process in the first place. Read in this way, cruising is not inherently an act of perversion (7). For many, cruising is the only means to satisfy repressed sexual needs by virtue of various heteronormative circumstances—some men are married, some are averse to normative means of courtship. For others, it is a place of thrill, hedonism and possibility. Reasons differ, but the shared object of desire renders cruising a powerful way to achieve the basic need of sexual satisfaction.

One by one, Moses and I make our way across these cruising sites, through Chinatown and up George Street into hidden bathrooms and dingy old buildings. We climb stairs and wash hands once, twice, and twice again, in busier locations, watching others as they watch us. Some sites are empty while others around the corner pulsate with life. We listen as the howl of hand driers melt into the sound of syncopated streams running from taps which never seem to stop, cubicle doors static and bolted shut, toilet bowls flushed at regular intervals. If we make our way inside, there are fresh handprints stamped onto the back of doors, and should you look down at the shadows which seep and ooze into your space, hands motion up and down and we begin to know that the desire for release is already at our fingertips. When I check in with Moses it is clear he remains conscious of his passive role as a curious observer: a tourist, a not-quite-voyeur, grappling with how the Sydney scene offers a kind of release he will not reach tonight. Moses is watching the world around him from this in-between space of anticipation, and against the conceptual focus of his art the irony of his melancholy does not escape me.

As our night begins to wane, Moses and I make our way downstairs to sit inside a bar located squarely beneath our last destination. Over beers and drunk businessmen, he tells me how he wants to speak truth to power, to resist Singapore’s sexual repression and proclaim queerness as a critical part of his own cultural history. Right before we part ways, my phone lights up with a message from a stranger on a hook-up app who wants me to come back upstairs. Moses laughs and asks if I’ll indulge him. My answer is a quick no, that I’m too tired.

As I ascend the escalator and enter the bathroom there’s a small, crackling speaker playing an unremarkable dance track. I check myself in the mirror and splash my face with water. I let the excess drip off and use wet hands to tussle my fringe. A man appears from nowhere and gives me a quick glance before going about his business just as quickly. Legs switch to autopilot and I find myself at the urinal furthest away from the entrance, directly in front of the last cubicle. I hear a knock behind me, and I look back to see a hand swiping underneath the partition, back and forth, a gesture that he knows I’m here.

The man from before stands at the other end, head down, unflinching at the conspicuous sound of flesh on wooden board. When I look at him I can only think about how to cruise and be cruised is to exist in one world, whereas those who remain oblivious stay firmly in another. I wonder how and if these two worlds will ever collide, whether this man will one day succumb to temptation and look back to see the truth of what is happening around him at moments like this. The hissing speaker swings the music into a new direction; a darker one with a warped French horn. Something takes over and I am lightheaded, but still in control. The door is ajar so I turn to enter: high off the thrill and possibility of something more.

Works from Moses Tan’s Memorial for Boogie Street series, featured in this article, were presented alongside works by Rathin Barman, Jessica Bradford and Erika Tan in By All Estimates, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 12 April – 26 May 2019.

Notes

(1) Kenneth Chan, Yongfan’s Bugis Street (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015), 80.

(2) ibid.

(3) Aaron K.H. Ho, ‘How to bring Singaporeans up straight (1960s-1990s)’ in Queer Singapore: illiberal citizenship and mediated cultures edited by Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012), 30.

(4) Laurence Leong Wai Teng, ‘Sexual governance and the politics of sex in Singapore’ in Management of success: Singapore revisited edited by Terence Chong (Singapore: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 586.

(5) It too extends to queer and non-binary individuals.

(6) Moses Tan, Mapping Melancholia (work in progress), as showed to me by the artist, 17 April 2019.

(7) While for some there is the added dimension of self-gratification through rendering others uncomfortable, it is dangerous to assume that all who cruise are of the same pedigree.

About the contributor

Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung is an Australian art critic. His writing imagines non-Western and decolonial frameworks for contemporary art.